‘50 Shades of Grey’ Manages to Elevate the Source Material, Yet Still Falls Short

Based on the best-selling novel by E.L. James, Fifty Shades of Grey comes with its baggage packed and our expectations loaded. James’ source material is, inarguably, poorly-written, with nearly-to-entirely offensive characterizations of both its leading lady and the kink community. But Fifty Shades of Grey pulls off the seemingly impossible, elevating James’ material to something more nuanced and human. And that’s largely due to the performance of Dakota Johnson, who carries the weight of all that baggage and our expectations on her back, so to speak.

For all its presumed indecency, Fifty Shades of Grey is a surprisingly decent film, not the least because screenwriter Kelly Marcel and director Sam Taylor-Johnson cut through the novel’s reductive and insulting attitudes toward women and BDSM. As with any adaptation, the inevitable comparisons will be drawn, but this is one film that distinctly elevates its source material in ways that are immensely gratifying…and in some that are, unfortunately (and weirdly) not.

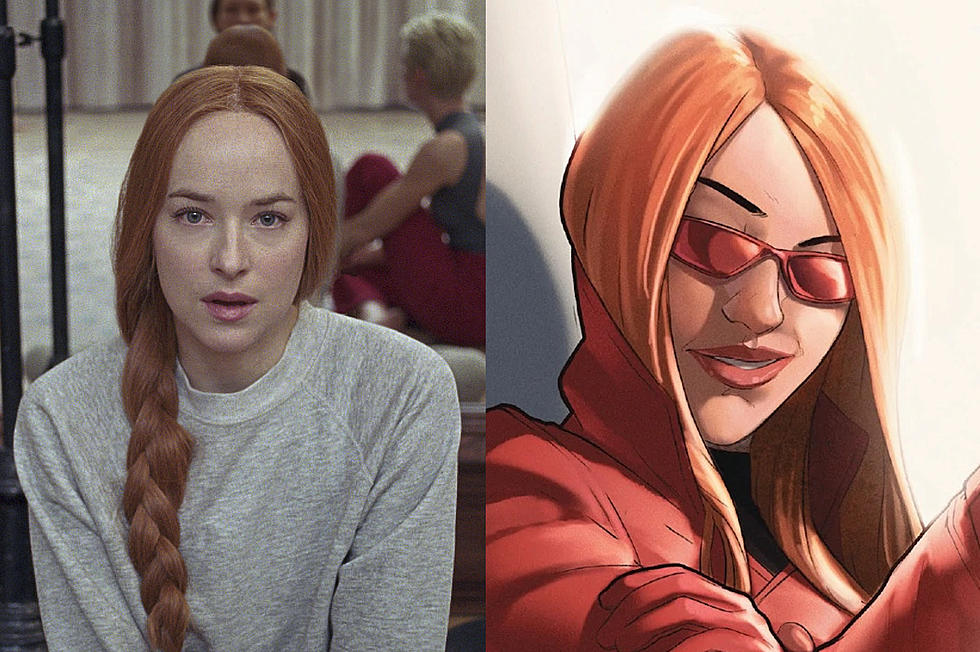

James’ version of Anastasia Steele is timid, naive, excessively needy and neurotic, whereas Johnson portrays her with striking subtlety. Johnson’s Ana is smart, playful, and more confident — she’s attuned to her feelings and desires. Her Ana is more self-aware than neurotic. She is a human, not a condensed type. As such, her blossoming relationship with billionaire bachelor Christian Grey (Jamie Dornan) typifies the beginnings of most relationships, both endearingly awkward and lustful in equal measure.

Dornan needs Johnson, and not merely in the fictional sense: the actor, who’s delivered such a fiercely fantastic performance on the U.K. series The Fall, is as bland and unmoving as a bowl of unflavored oatmeal in Fifty Shades of Grey. Dornan has none of the subtle energy and charm of Johnson, who often appears to be acting opposite a stoic (but handsome) mannequin. Perhaps as an intentional inverse of the novel, Dornan’s Christian exists in service to Ana’s story, whereas James portrayed Ana as a wet dishrag whose entire life becomes a reaction to the actions of one man.

But Fifty Shades of Grey isn’t the fastest-selling R-rated film of all time for the allure of its stars. When we enter the movie theater, we, like Ana, are engaging in our own contract, where we expect the film to deliver on certain promises without negotiation. James’ novel became a best-selling phenomenon due to its sexually explicit subject matter — the BDSM element was a curiosity to many, just as odd or quirky as the concept of a woman signing a contract to sexually submit to the whims and desires of a wealthy man. In this economy, exchanging a little sex with a handsome billionaire in exchange for a new Macbook and a shiny new car makes Fifty Shades seem like the new Pretty Woman — if the Pretty Woman in question were sexually inexperienced.

The novel’s approach to BDSM and consent was exceedingly simplistic and almost willfully ignorant to the realities of a healthy kinky relationship. Ana had little agency, and her consent (or lack thereof) was often outright ignored by Christian, who was portrayed as a wounded man whose mental and emotional deficiencies defined his sexual tastes. In reality, the vast majority of kinksters are average and mentally sound.

While the film’s portrayal of sex and kink is decidedly tame, like an entry-level BDSM Basics course, Marcel and Taylor-Johnson’s explorations of both relationship dynamics and a healthy, consensual sex life are more complex. Fifty Shades of Grey isn’t so much an adaptation as it is loosely based on the source material, thankfully using James’ novel as a rough outline rather than a Bible. There are typical, small moments of fan service, but the film ultimately expands on its source.

What the film gets so right are specific ideas, like Ana deciding to explore new sexual concepts not just for someone else’s pleasure, but for her own possible pleasure, too — how will she know until she tries? We don’t know what we’re into sexually until we discover it, and Ana is open-minded and respectful of Christian’s proclivities, willing to be—in the words of sex advice columnist Dan Savage—good, giving, and game. But there’s also a distinctly relatable push-pull between Ana and Christian: where Ana is game to try new things and explore Christian’s sexual preferences, Christian is stubbornly opposed to engaging in Ana’s desires. Where Christian’s tastes are more singularly sexual, Ana is more turned on by romantic notions and the basic dating life that she’s never had.

The film becomes something of a war between sex and romance, with Christian refusing to compromise for someone who makes compromises for him. Never once do we feel that Ana compromises herself, though, and rather than unhappily tolerate his controlling behavior as she does in the novel, Johnson’s Ana flirtatiously toys with Christian while establishing firm boundaries. At the heart of this pairing is the very basic idea that a relationship is filled with healthful, happy compromises, but that a successful relationship also beautifully marries sex with romance, something that Christian refuses to understand or do.

Unfortunately, for all that the film gets right about relationships and consent, it spends far too much time romanticizing its sex acts. In each of these scenes, the camera slowly and carefully caresses its subjects, treating sex not as instinctual, but as calculated softcore choreography. The BDSM elements are almost annoying tame, and the film’s, uh, climax is exceptionally disappointing. It’s near the end of the film where Ana’s reactions to Christian’s proclivities become somewhat irrational — she goes from empathetic and eager to understand to judgmental with alarming bipolarity. Similarly grating is the film’s insistence on sticking with the source material on at least one point: that Christian is the way he is because of some vague, mentally distressing and possibly abusive moment from his past.

Fifty Shades of Grey ignores the opportunity to establish that the majority of people with a particular fetish didn’t arrive to that preference from a moment of anguish or abuse, but that human beings are individuals with individual tastes, each of us wired differently in some subjective and often indefinable way. For Ana to feel heartbroken is understandable, given the cold and emotionally unyielding man for whom she’s fallen, but for her to feel heartbroken after he merely spanks her harder than he has before seems baffling. It’s a misguided moment because Ana has every right to feel bad, even and especially about something to which she gave her consent, but her reasoning is excessively confusing, taking the film into murky territory that questions ideas about post-sex regrets. It’s here that Marcel and Taylor-Johnson relinquish their own control, and sadly fail to keep their grasp on the subject matter.

Fifty Shades of Grey is, by no means, a bad movie. At its worst, it’s confused and misguided, but never once comes close to mimicking the insulting and small-minded characterizations of James’ novel. At its most mediocre, the film hardly captures the raw nature of sex, nor does it push cinematic boundaries to normalize sexual fetish, instead delivering a Pumpkin Spice Latte version of kink — it’s horribly basic. At its best, the film is a surprisingly charming exploration of relationship dynamics, with an intensely great, star-marking performance from Johnson, who breathes life and nuance into a character who desperately needed it.

More From ScreenCrush