After ‘Blade Runner 2049,’ Is Deckard a Replicant or Not?

The following post contains SPOILERS for Blade Runner and Blade Runner 2049. Be prepared: All those secrets of the sequel are about to be lost in time, like tears in rain.

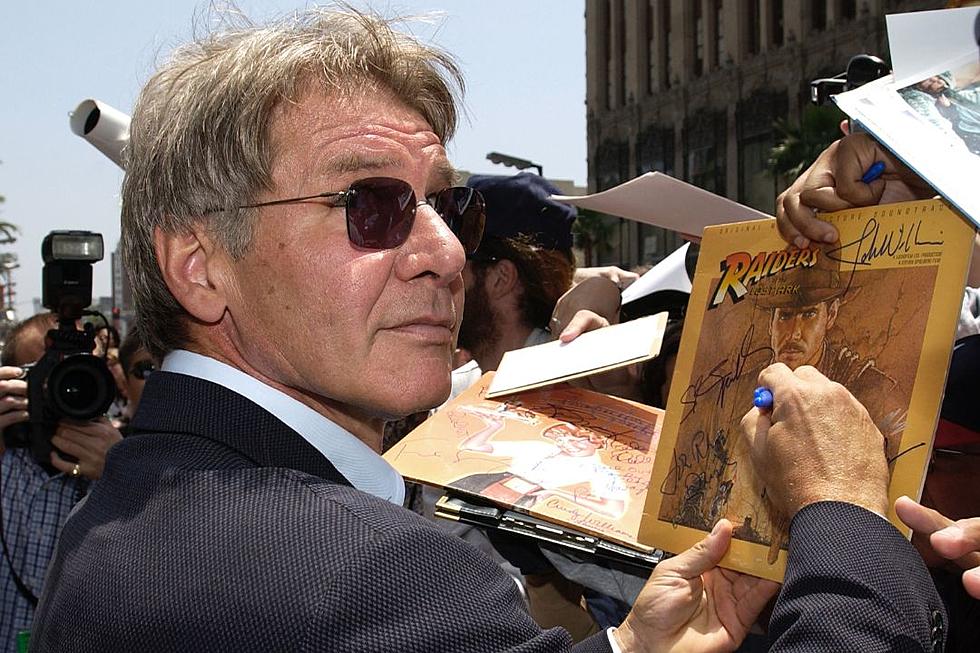

There were a lot of reasons to be excited about Blade Runner 2049. Its director, Denis Villeneuve, is one of the boldest working in Hollywood today, and his cinematographer, Roger Deakins, ain’t no slouch either. Villeneuve assembled a terrific cast, including Ryan Gosling, Jared Leto, Robin Wright, Dave Bautista, Sylvia Hoeks, Ana de Armas, and Harrison Ford, the star of the original Blade Runner. In the 35 years since the first film, its cautionary tale about a ruined environment populated by artificial intelligence that is on the verge of replacing humanity, has only grown more relevant. The original Blade Runner was set in 2019, and even if its director, Ridley Scott, working from a novel by Philip K. Dick, was a little bullish in predicting just how fast technology would evolve, his guesses about the general state of the world were eerily on the money. If ever there was a time to make another Blade Runner, this was it.

But there was at least one reason to be deeply concerned about Blade Runner 2049: The fear that the film would offer an explanation to one of cinema’s most beloved enduring mysteries. Ford’s Blade Runner character, Rick Deckard, is a cop who hunts down “replicants,” its future’s robotic slaves. Over the course of the film, Deckard discovers a replicant that’s so advanced it doesn’t even realize it’s a robot. Which raises the ultimate question: Could Deckard be a replicant too?

In its various cuts, Scott’s Blade Runner hinted strongly that he might be, without ever offering a definitive answer. But the sheer existence of a new Blade Runner 35 years later, with Ford in the film as a much older Deckard, would seem to solve that mystery once and for all, which would retroactively ruin a lot of the fun about the old film. For a long time, that fact alone made me very nervous about Blade Runner 2049.

As it turns out, my fears were unfounded. Villeneuve and his writers, Hampton Fancher and Dennis Green, found a way to turn what could have been their sequel’s biggest weaknesses into one of its greatest strengths. The way Blade Runner 2049 advances Deckard’s storyline is just about perfect. To fully understand it, let’s first look back at his role in the original Blade Runner.

Deckard in Blade Runner (1982)

The focal point for the Deckard-as-replicants theories is the end of Blade Runner, when he and Rachael (Sean Young) the replicant who doesn’t know she is a replicant, go on the run to avoid a fate like the one that’s befallen the rest of the movie’s robots. As they’re preparing to leave Deckard’s apartment, he discovers an origami unicorn on the floor.

The origami is the calling card of another blade runner named Gaff (Edward James Olmos); his line about how it’s too bad she won’t live refers to the replicants’ brief lives; they are programmed to “die” after just four years. In every version of Blade Runner (and there are, at last count, 3500 cuts of the film), the origami tells Deckard that Gaff has been in his apartment and chosen to spare Rachael’s life. But in the director cuts of the film, it also has an additional meaning involving Deckard.

Earlier in the film (at least in the cuts that include this scene), Deckard has a dream about a unicorn. And he also tells Rachael in another scene that the memories that she believes she has that prove her personhood are all false implants, lived by someone else and uploaded into her brain. If what Deckard says is true, and if he has a dream of a unicorn, and if Gaff leaves that unicorn origami specifically because that dream is another artificial implant, then Deckard is almost certainly a replicant like Rachael.

There are other, smaller clues as well, like the many photographs in Deckard’s apartment (replicants, we’re told, are particularly fond of old pictures). Replicants’ eyes also reflect a strange red light from certain angles, and in one scene Deckard seems to have that same red light bouncing in his pupils. The Deckard of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? was a real human being (he supposedly passed the Voight-Kampff test that measures a subject’s humanity). At most, Scott’s film is far more ambiguous and, at least in his preferred cuts, borderline overt in identifying him as a replicant. Which brings us to...

Deckard in Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

First of all: Deckard’s in Blade Runner 2049, he’s just not in much of it. He’s more like the unseen presence motivating all of the action, much like Mark Hamill’s non-role as the missing Luke Skywalker in Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

In 2049, Deckard has been missing for decades, since shortly after the events of the original film. K (Ryan Gosling), a new blade runner, needs to find him because he holds the key to a mystery that could upend the future’s social order. (One more time now, I will warn you that SPOILERS are coming.) On a routine assignment, K discovers the remains of a woman. The evidence suggests the corpse belonged to a replicant, and that this replicant did something that should be impossible: She gave birth to a child. K follows the evidence and realizes the dead replicant is Rachael, and the father of her child is Deckard. But he still needs to find the replibaby (we’ll work on that name) and Deckard himself.

It takes Gosling almost two hours to confront Ford onscreen (although we hear his voice, in recordings of Voight-Kampff test pulled from the first Blade Runner, much earlier). But the first possible confirmation that Deckard is a replicant comes in the very first scene, when Villeneuve reveals that K is a replicant. That doesn’t necessarily guarantee that all blade runners are replicants, but it definitely means that some are. Based on the sequel, it doesn’t seem unusual for a replicant to hunt other replicants either.

This scene is also important in establishing that not all replicants are beholden to the four-year lifespan that was crucial to the plot of the original Blade Runner. In the earlier film, the robots supposedly only survive for this brief amount of time and then self-destruct. But when K finds Dave Bautista’s Sapper Morton, he finds out he’s been living alone on his protein farm for decades. Clearly, the four-year lifespan isn’t as firm as it seemed, which makes it possible for Deckard to look 35 years older than the events of Blade Runner and still be a replicant.

Over the course of 2049, we also learn that replicants can’t have babies; despite his best efforts, nutty robot designer Niander Wallace (Jared Leto) can’t figure out how to make his robots procreate. That’s why he sends his henchwoman Luv (Sylvia Hoeks, secret Blade Runner 2049 M.V.P.) after K; he needs Deckard to understand how this dead miracle baby happened. The fact that replicants can’t, uh, replicate could suggest that Deckard isn’t one, but even with his DNA in the mix, you’ve still got Rachael involved. Unless she was a human all along, that would preserve this medical mystery.

The scene that fans will focus their energies on comes late in the film; after Luv has kidnapped Deckard and brought him back to Wallace’s office. I don’t have the scene in front of me (it’s not online, at least for the next couple minutes), but the thrust of the conversation is Leto telling Deckard he was “programmed” for the special purpose of creating life with Rachael. Then, just when it looks like 2049 is going to finally solve the ultimate replicant riddle, Wallace hedges, and suggests that his “programming” might come from biology rather than engineering. The forces that brought the couple together could be mathematics, or it could just be love. That opens the door just enough to keep you wondering. In the end, the question remains unanswered.

Some audiences who want a resolution might be frustrated by that scene. Personally, I loved it. It takes incredible skill (not to mention serious cojones) to return to one of the most famous ambiguous endings in movie history and build on top of it without erasing or negating the ambiguity. It’s the rare expansion of a mythology that broadens and enriches the previous work without radically altering anything that came before.

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner predicted a lot of things about the world of the 2010s. But its most accurate guess may have been to foresee a world dominated by puzzle movies, where audiences obsess over clues on message boards, YouTube videos, and blog posts. The original film was far ahead of its time. The sequel is entirely of its moment. And now it’s in the hands of internet theorists to decide what they think it says.

The 25 Greatest Sci-Fi Movie Posters Ever:

More From ScreenCrush