‘Krisha’ Director Trey Edward Shults on His Personal Family Drama and Being Terrence Malick’s Intern

There’s no doubt about it – Trey Edward Shults’ feature film debut Krisha is intense as hell. It’s a family drama about addiction and alcoholism that's difficult to digest, yet one with little resemblance to films about similar topics. From the aggressive, yet exhilarating Trainspotting to the utterly traumatizing Requiem for a Dream, many films about addicts rely on graphic depictions of substance abuse to portray how low one can fall. As important as such stories can be, sometimes smaller, personal traumas resonate the loudest.

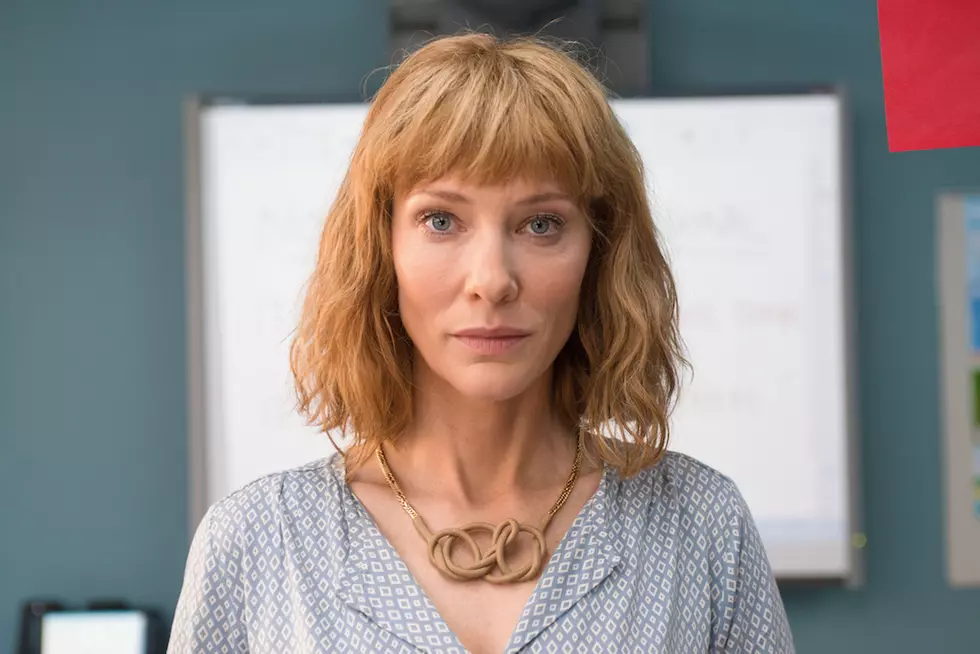

In Krisha, we follow the titular middle-aged woman as she visits her family for the first time in a decade on Thanksgiving Day. In attempting patch up deep wounds, Krisha is drawn back to drugs to cope and the audience is taken on a rattling, frantic ride through her wavering stability. The most potent and heart-breaking aspect of Krisha is how deeply personal it is. Shults wrote and directed the film following the overdose and death of his cousin, and also acted in it, cast his real-life aunt (Krisha Fairchild) as the lead, his mother (Robyn Fairchild) as Krisha’s sister, his grandmother (Billie Fairchild) as their mother, and filmed the movie in his parents Texas home in nine days.

Shults shared his journey of turning a personal family trauma into his feature film debut, which won the Grand Jury Prize and Audience Award at SXSW 2015, as well as the John Cassavetes Award at this year’s Indie Spirits. The filmmaker also told us about his experience as an intern on two Terrence Malick films, the upcoming Voyage of Time and Weightless, and how it influenced is work on Krisha.

How did something so personal to you and your family become a short and eventually a feature film?

It started in 2011 when my cousin came home for a family reunion and she relapsed, and two months later she overdosed and passed away. I started writing the first version of the script probably a month or two after that. Then summer of 2012 we were trying to make a feature; [it was the] worst week of my life. We failed, I didn’t know what I was doing. I was a sole producer, I had like $7,000 in my savings. We didn’t have all these things we literally needed, but I was stubborn. I had a nervous breakdown behind closed doors the whole week because the movie meant a lot to me and I thought it could be special and I knew weren’t making it. But we were getting some good stuff, so I took two years and turned that into a short film.

That short film was something I was actually proud of and that got into SXSW 2014 and people seemed to dig it there. A couple people were saying, “Why don’t you do a feature version?” Just hearing that and taking a second to think about it I realized I had to do it again, I wasn’t done with her story. The short was the movie you see now compressed to 14 minutes, that same arc. It was like 14 minutes of intensity. It actually works, you wouldn’t think that, but it works. But I feel like it doesn’t have as much depth as the feature and I think the feature can be really funny or intense, or really sad and emotional. But the short is just really intense.

Is it released or available online anywhere?

It’s not. I never released it because it totally spoils the feature, and I don’t have the rights to songs.

Do you think anything came out in the feature that wouldn’t have had you not gone through the process of failing and making a short first?

Totally, 100 percent. I think a lot of the creative editing, like snapping back-and-fourth in time, even [Krisha's] face in the opening. I discovered so much. [In] that first draft of the feature, I still hadn’t figured it out. I don’t know what it was, but I was stubborn and was like, “I gotta do it.” So in that there was so much discovery just in re-editing for two years and writing again, so much discovery that I had to go through to get to the movie you see now.

The opening and closing moments with the camera focused on Krisha’s face really establish the intensity of the film. How did you arrive at the choice to begin and end with those shots?

[In] that script from 2011, it opened with her face, but it never returned to it at the end. It had this more like – I dunno, cheesy [ending]. It wouldn’t have worked. Originally I don’t know what I was thinking, I just liked that image [of her face]. I had an idea that it would happen and maybe a credit sequence would go over it, and it’s her trying to keep her eyes open the whole time and she can’t so she just closes them. And then we shot it with Krisha and it was really powerful. Then I had that in the editing room and realized I had to go back to this woman’s face, it had to start and end with it.

Thinking about it more, I really dug the idea of the movie as a confrontation with the viewer. Whatever it is, whether you’re confronting your own demons, Krisha’s, whatever you take from it. The whole movie, it’s building and it ends, you can say abruptly, but what’s important to me is her face at the very end there and what that says to you. I’ve had different people say totally different things. I’ve had people [see it] closer to what I was thinking, where it’s a moment of realization. Sometimes you have to go to your lowest low. That happened to me in my life; [I went] to my lowest low before I could snap out of it and realize, I’m not just the victim here, I’m creating a lot of this.

It’s interesting you say victim because what struck me is how the film avoids victimizing or vilifying anyone, including Krisha. Was your approach more about capturing the whole family’s collective experience?

Totally. I think what it started with was wanting to go on this journey with Krisha, to never judge her, to never make her the villain and experience this with her and have a ton of empathy for her. The movie’s from her point of view, but I wanted to be able to have sympathy for the rest of the family as much as possible. Even the scene with her son [played by Shults], you don’t know their past. […] So the whole breadth of all of that, and feeling the grandma and her sister when she’s trying to get to her. Those are the three people who are the most important to her, her son, [her mother] and her sister, those are the people she’s needing that connection with.

What was that like to work with your relatives on such a personal film?

It was actually lovely. You’d think it would be a nightmare. At first even I was like, “Can we pull this off?” We failed the first time, but going into the feature again people were down and excited. The short, worst week of my life; [the final feature], best week of my life – beautiful, collaborative, amazing. It felt as we were making it very special.

Did you have to step back as a son and a nephew while directing your mom and aunt?

I always had to be objective and see if we were getting the scene or not. Even though they’re my mom and aunt, they’re incredibly talented. Krisha, she’s a pro, she’s nothing like the character at all. She’s a sweet hippie who loves dogs, doesn’t drink wine. The movie rests on her shoulders, I don’t think it would work at all without her performance. […] It’s not what I did as a director, it’s because she’s amazing. My job, if anything at certain moments, was [to say], just take it back a hair, and then she kills it. My mom, that was more knowing when to get out of the way and how to set up the right environments.

[…] Then other stuff with my grandma, that was like a documentary. She didn’t know we were making a movie, the camera was hidden. My favorite scene is the long-take when [my grandma] meets the whole family, because it’s real, it’s not scripted, it’s serendipitous. She messes up Krisha’s name, she starts talking about her mom. She starts talking about her lineage, and then if you look at the framing, it’s my grandma in profile, Krisha in profile, I’m behind Krisha, the baby’s behind me. It’s literally family lineage in the frame. It’s such an important scene because that’s the final thing – that scene is really [Krisha's] downfall. If you think about it she probably hasn’t seen her mom in 10 years, she’s hoping to come and mend the relationship, but the mom’s gone, she has dementia now. It’s heartbreaking because in that moment she gets it, “I will never be able to mend the relationship with my mom.” […] I know my grandma has dementia, so as long as my mom and Krisha got the idea of the scene and [could] push it a little bit. So I had a feeling it would work, but the way it ended up working, it totally exceeding my expectations.

In comparison to the single-take scenes in the kitchen, were those also experimental or were they outlined in the script?

Totally different approach. The kitchen scene, when it’s one long take out of the turkey and [the camera is] spinning, that was in the script. The aspect ratio changes were in the script. We had a very strict structure so even when we were improvising we knew exactly where we could go into the story and give more life to it.

The sound design throughout the film is something that really stands out and made some scenes, to me, feel like a chaotic ballet of sound and visuals. What inspired that?

I love that. For certain stuff, the first time Krisha’s in the kitchen, we actually call that piece “Kitchen Chaos.” But the mentality was this is playful chaos. It should be kind of crazy and overwhelming, but still kind of fun. It’s not heavy chaos, which comes later in the movie. [Composer] Brian [McOmber] did this screwed-up prepared piano piece and little movements in the song would echo movements in the characters, just good weird stuff. And you combine that with the chopping and the slamming in the kitchen and just get creative with that and meld the two together to where you’re not sure if you’re really hearing chopping or if that’s the music. […] That was always kind of the idea because the music is very subjective, trying to get you in Krisha’s head. It starts on the outside and then you just follow her. We’re always trying to get right in her head and then in the end we literally are, we go inside her head and see things she does.

Before Krisha, you were an intern for Terrence Malick. What was that like?

It started when I was 19, I got on as an intern for Voyage of Time. I was living in Hawaii for the summer with Krisha and I got on this movie. The film loader taught me how to load magazines. The first time I was doing it we were outside filming the volcano and lava was right by us and it was raining. But I did OK and the DP liked me so he got me on all these other shoots. I was a Terrence Malick fan too, but Terry wasn’t there for that stuff. Most of it was me and four other guys, not Chivo, this other DP Paul Atkins, really basically shooting second-unit footage for Terrence Malick, which anyone who watches him knows second-unit footage is very important. After that I came home to work for my parents, and then as time would pass I would go and work for [Terry] again. I worked on Weightless, which was awesome. That was Chivo, Terry, Ryan Gosling, Michael Fassbender, Natalie Portman. It goes from a couple of guys filming footage to literally working and watching how unorthodox he is. It was beautiful. And Terry’s a sweetheart. He’s like a cooky dude who always wears a Hawaiian shirt.

Did watching him on set influence your style of filmmaking?

What I hope is that it hasn’t literally influenced my style because I think Terry is one of a kind and you’re a fool to try and do what he does. So I didn’t want that, but what I do think rubbed off is his spirit, how unorthodox he is, and how open he is and how at his age he’s making the most experimental movies of his career. It’s inspiring. We didn’t make our movie in the same way he makes his at all, but I had that mentality and that approach and that looseness.

You’ve described your next film with A24, It Comes at Night, as your version of a horror movie. Can we expect something traditional to the horror genre, or more intense and personal like Krisha?

Both. That one I wrote right after my dad passed, so it comes from a deeply personal place. The opening scene is literally what I was saying to my dad on his deathbed. I [was] bawling writing the scene, but then I wrote out a narrative movie that has nothing to do with it, but it’s still coming from those emotions, like death, fear, regret. Heavy stuff, which I think is more palatable in a genre thing, or else it’s going to be a rough movie. This probably will be a rough movie, but hopefully pleasurable in certain ways. It’s just as much a family drama as it is with the horror elements. The closest thing I can think of is The Babadook.

Krisha is now playing in select theaters.

More From ScreenCrush