Reel Women: What ‘The Heat’ Can Teach Us About Friendship and Feminism

There's this misunderstanding that feminism means blindly supporting your fellow woman for the sake of supporting women, but as Sandra Bullock and Melissa McCarthy show us in 'The Heat,' that's not how feminism -- or friendship -- works at all.

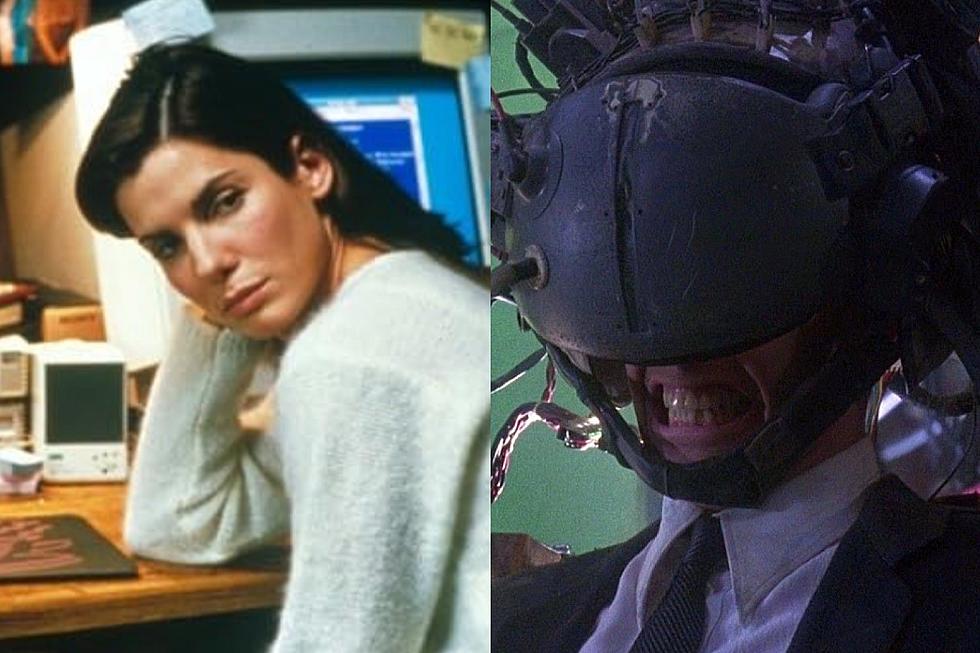

Written by Katie Dippold and directed by Paul Feig ('Bridesmaids'), 'The Heat' follows overly-confident and alienating FBI agent Sarah Ashburn (Bullock) and foul-mouthed, obnoxious Boston cop Detective Mullins (McCarthy), who are unwittingly paired up to solve a string of drug-related murders. Using buddy cop theatrics usually reserved for the pairing of men, the film teaches us a lot about female friendship.

A friendship is just like any other relationship -- there are ups and downs, and you don't always get along or agree with one another, and sometimes one friend kicks the other friend in the ass to get them moving along to where they need to go in life. Feig covered similar territory with 'Bridesmaids,' with a story of envy and self-disillusionment, but here the focus is on two women who have never met before and have seemingly divergent personalities, overcoming their surface differences to find mutual respect, admiration, and affection for one another.

McCarthy is the obnoxious one with a soft center, of course (a type she plays consistently well), and Bullock is the more uptight one who plays by the rules and sometimes lets her arrogance get the best of her. If this were grade school, Mullins would be the bully, acting out as a defense mechanism of sorts, and Ashburn would be the goody two-shoes bookworm. But "obnoxious" and "arrogant" are sort of negative descriptors, and time and again we watch these women dismissed or evaded by their male counterparts for the very qualities that would be praised if they were men. Ashburn is called "competitive," while Mullins is avoided like the plague for her brassiness. In a male buddy cop comedy, these characters would only be scorned if they were loose cannon types, the kind of cops who often got people hurt or broke too many rules. There's allusion to that with McCarthy's character, who has a rap sheet of her own.

These two women are able to complete one another, like two halves of a whole. Mullins has the brash personality and aggression that Ashburn lacks, while Ashburn takes time to calculate her next move and consider the more scholarly aspects of her training. Together, they can teach each other a lot, but the film isn't interested in some montage where they school each other or learn new techniques. The script naturally allows these women to grow and understand each other, in ways that are sometimes subtle (tactics in interviewing suspects or creating diversions) and sometimes not (meeting Mullins' family), but they aren't always supportive of one another. A big part of feminism is equality, and recognizing that we are all equal -- men and women, women and women -- and that equality is based on humanity, not an ideal. And humanity is flawed.

A little criticism is good because it helps us recognize our mistakes and inspires self-reflection. The clashing personalities and behaviors of these two women allow them to see what they're lacking and where they're perhaps making some detrimental mistakes. And that's what we look for in real-life friendships, isn't it? We don't want people who are exactly like us -- we want them to have some superficial similarities (pop culture preferences, for instance), but we want people who will challenge us in any relationship. We want those who will not only reflect back the best parts of ourselves, but who have qualities that we lack and aspire to possess. We want to surround ourselves with people who will make us want to be the best version of ourselves.

At the heart of 'The Heat,' beyond the profanity and buddy cop banter and the occasional explosion, is a tale of finding unexpected friendship and understanding, of what it means to find a meaningful friendship that involves mutual support and respect -- and how you don't have to make a movie where women slight each other over men and then have some teary reunion set to some outdated female empowerment slow jam to get there. Women can be friends even -- and especially -- when men aren't involved. And we can certainly be friends even -- and especially -- when we don't always agree.

More From ScreenCrush