‘The Book of Henry’ Is a Once in a Generation Good-Bad Movie

The following post contains SPOILERS for The Book of Henry. You’re going to think I made a lot of it up, but I promise I didn’t.

Let me pitch you a hypothetical scene from a movie. A precocious little boy in adorable, oversized glasses comes running to get his mother, who is stress-eating in the kitchen. The boy holds a tattered red notebook. “Mom!” the boy yells “I think Henry wants us to kill Glenn!”

The boy and the mother look through the book, which contains detailed instructions on how to kill “Glenn,” the local police commissioner who is apparently sexually abusing his stepdaughter. The mother is aghast at his actions, but refuses to commit murder. She wants to call Child Protective Services instead — but there’s a chapter in the notebook explicitly called “Why Calling Child Protective Services Is Not an Option.” There’s no other option, the book insists, except assassination. The boy is convinced; the mother is still skeptical. When he pushes her to give in, she puts her foot down. “We are not murdering the police commissioner, and that is final!” End of scene.

Now, about our hypothetical scenario: What genre would you say it belongs to? The subject matter — child abuse, violent retribution — suggests a revenge picture, or maybe a bleak thriller. The fact that the whole murder scenario appears in a notebook that seems to have anticipated its readers’ every thought could come from a work of magical realism. But the dialogue, particularly the scene-ending punchline, sounds like something out of a broad comedy. It’s a strange mix of stuff, like a cookie made from a batter of butter, borscht, and falcon eggs.

Except this strange mix isn’t hypothetical. The movie is real, although if I hadn’t just watched it with my own eyes, I might not believe it. It’s called The Book of Henry. Ludicrous as it may have sounded, the dialogue above is quoted verbatim:

My condensed “hypothetical” version of that scene barely scratches the surface of its crazy. The all-important notebook was written by a crusading, 11-year-old genius named Henry. Henry might be the smartest person on the planet. He pays all of the family’s bills, and, in his spare time, makes hundreds of thousands of dollars playing the stock market. He creates intricate Rube Goldberg devices and writes inscrutable mathematical formulas on his bedroom walls. When he gets sick and has to go to the hospital, he looks at his own MRI and diagnoses his condition.

Yes, Henry (Jaeden Lieberher) is very sick. Dying, in fact. With his final days, he writes this crucial notebook, planning, down to the last detail, how his mother Susan (Naomi Watts) must murder their neighbor Glenn, in order to rescue his stepdaughter Christina (Maddie Ziegler). I’m not an 11-year-old know-it-all, but it’s hard for me to believe this is the only plan a genius can think of. Henry (and, later, Susan) witness this abuse first-hand; they watch it take place through a window in their house. Henry couldn’t have used his thousands of dollars to buy a camera to record some evidence? Or how about using some of that money to bribe an official into taking a hard look at this case? There’s no ambiguity here; Glenn is 100 percent guilty. Bribery isn’t ideal, but it’s less morally compromised than, say, killing a guy.

But Henry’s the genius, not me, so fine: Murder it is. And genius Henry decides the best way to kill Glenn it to shoot him. To guide his mother, who can’t even be counted on to pay her family’s bills or parent her children properly but is now expected to not only shoot a police officer but then cover it up, he leaves behind a series of cassette tapes to supplement his notebook; Susan listens to them, and often talks back to Henry’s instructions. In fact, Henry is so brilliant he seems to have anticipated every single thing his mother will say and do and responded to it on the tape, to the point where it often sounds like Susan is carrying on a conversation with her dead son’s ghost. He even gives her pointers on the use of a sniper rifle. (Genius Henry also knows advanced shooting techniques.)

Again, nothing we have seen suggests Susan is capable of committing this violent act. She leaves her youngest son (Room’s Jacob Tremblay) unsupervised in the bath so she can play video games, can’t figure out the complexities of online bill pay websites, and ignores her kids to get drunk with a co-worker (Sarah Silverman) on multiple occasions. Now her son (who, again, is the world’s greatest genius) thinks she can become a competent sniper, kill one of the most powerful men in town in their backyard, and then cover it up? It’s such a bad and stupid idea that I’m starting to think that Henry’s actual plan was to get revenge on his mother for all the years of neglect by having her commit murder, get caught, and then go to jail. “That’ll teach you for making me balance your stupid checkbook, Mom!”

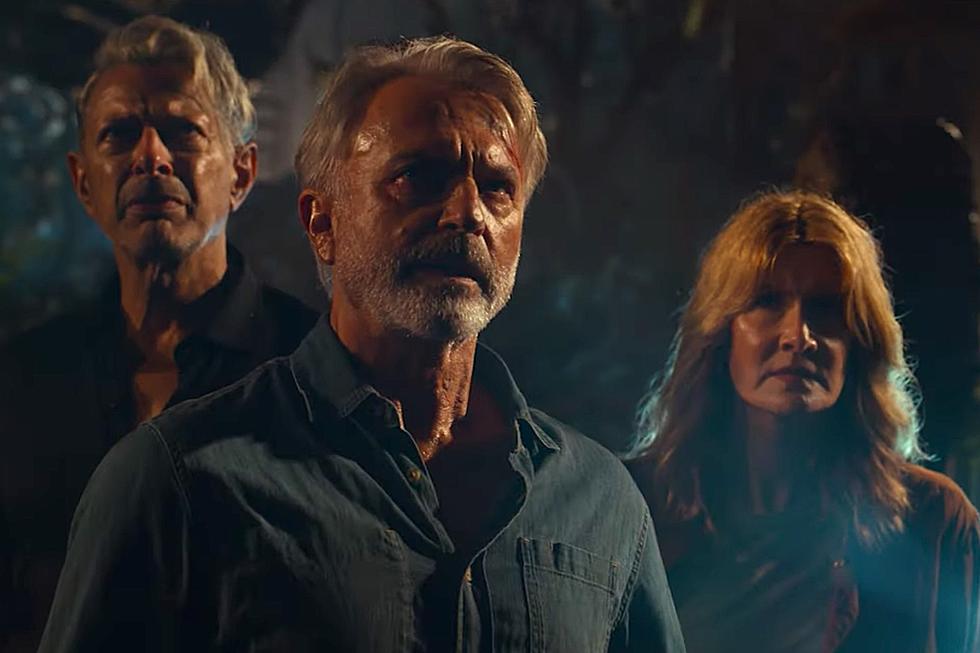

If the movie had had the courage to reveal Henry as a kind of Saw-level super-villain, that would have been amazing. But director Colin Trevorrow, who followed up the massive smash Jurassic World with this massive bomb, treats Henry as a messianic figure. Everything in The Book of Henry implores the audience to view Henry as the Second Coming, from the title, to the character’s last name (Carpenter), to the way Henry essentially dies for our sins, to his ability to speak (and almost converse) with family members from beyond the grave. Henry’s death scene, lying in his mother’s arms on the floor of his hospital room, even evokes a Lamentation of Christ painting. So, to recap: This is a Christ parable about a magical, godlike being who died so that his horrible mess of a mother could kill a guy and adopt her abused stepdaughter (who The Book of Henry treats like a plot device rather than a person, up to the moment she seemingly heals her mental trauma through the power of interpretive dance during the film’s climactic school talent show).

It’s this sort of deranged logic that makes The Book of Henry a truly unique good-bad movie. On a technical level, it’s not bad at all. The cinematographer, John Schwartzman, has shot films ranging from The Rock to Trevorrow’s Jurassic World. A professional through and through, he brings a homey warmth to every frame set inside Susan’s impossibly large house. The film’s score is by Michael Giacchino, one of our very best film composers, and he frames every emotional beat Trevorrow wants to hit. Editor Kevin Stitt, who also worked on Jurassic World with Trevorrow, crisply brings together several plot threads in the film’s finale. (The plot threads are insane, but you can’t fault how they’re combined.) And Trevorrow assembled a fine cast of actors, who all treat the material seriously.

But that’s just it: They treat one of the craziest premises ever devised with total seriousness. The fact That Book of Henry looks and sounds so slick, the fact that millions of dollars were sunk into this absurd blend of coming-of-age-story and rape-and-revenge thriller, only makes it more delightfully baffling. And apparently everyone involved thought it made perfect sense.

On some level, I’m sympathetic. Beneath the layers of misguided suspense and schmaltz, The Book of Henry does have an important message about the dangers of apathy, which Trevorrow and screenwriter Gregg Hurwitz spell out in this scene:

I don’t doubt Trevorrow’s good intentions. But good intentions sometimes create bad movies. And while apathy is a major issue, I’m not sure the correct solution to it is teaching your slacker mom how to become a military-grade sniper.

In 1964, Susan Sontag wrote that the essential element of a camp movie is “seriousness, a seriousness that fails.” Great camp, she said, had the “proper mixture of the exaggerated, the fantastic, the passionate, and the naïve.” With its ultra-serious message, exaggerated characters, fantastic scenario, passionate performances, and naïve belief in its own twisted idealism, The Book of Henry may be the greatest camp classic of my lifetime. I love it so much that I’m currently building an elaborate Rube Goldberg machine in my basement that, when accidentally activated, hits a ball that falls into a cup that spins a top that falls on a lever that flips a toy bird that turns on a television where The Book of Henry is playing on an endless loop.

More From ScreenCrush