Burning the Book: ‘The Revenant’ and When Adaptations Are No Longer Adaptations

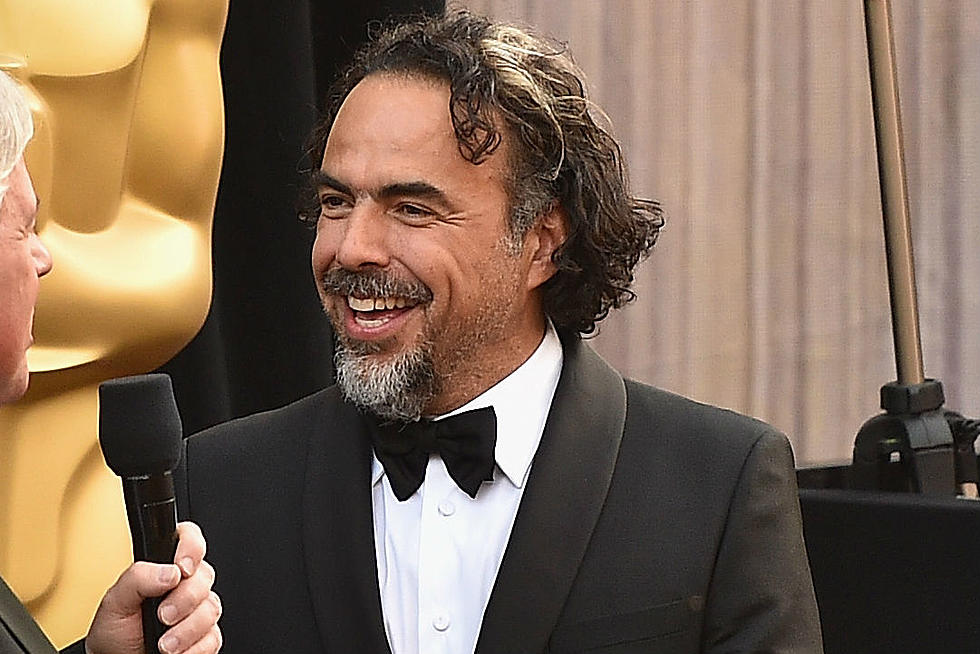

When Alejandro González Iñárritu’s The Revenant fades to black, you see a very unusual credit wedged between the familiar titles: “Based in part on the novel by Michael Punke.” Not “based on,” but “based in part.” And then it clicked. This was why the movie I had just watched didn’t resemble the book I had just read. For once, here was a lousy adaptation of a good book that at least had the nerve to admit it was throwing out the source material.

There’s a reason “the book was better” is a cliche at this point – not every great book can make the successful leap across mediums and the results can be messy and dispiriting. Some adaptations go under fire for missing the point of the source material. Others are forced to strip away so much detail that they feel like a pale shadow.

And then you have movies like The Revenant, which throws the book of the same name in a fire and marches into new territory altogether.

The ways in which Iñárritu and co-writer Mark L. Smith diverge from Punke’s historical western are fascinating. They take the central core of the book (frontiersman Hugh Glass is mauled by a bear, left for dead, and embarks on a dangerous journey to claim vengeance) and literally nothing else. This is an adaptation in the loosest sense of the term. To those who have read the book, it is a jarring experience. Cinematic whiplash. One wonders why Iñárritu bothered to even acknowledge the book if he was going to diverge this much.

The Revenant fails as a film – it’s po-faced and aggressively silly, overtly macho and stuffed with cliches, visually astonishing by emotionally empty – but that’s a conversation for another time, because it fails spectacularly as an adaptation. If the film itself was good, it would still be a nightmare of a translation.

And it’s fascinating! Once a book reader realizes that the film holds no allegiance to the book (which should hit around the 30-minute mark), the “Wait, what’s going on?” can end and the “Huh, I wonder why they made that choice?” can begin. Not since Winston Groom’s scathing, bitter novel Forrest Gump was transformed into a slice of feel-good Americana has a major, star-stuffed Hollywood movie taken so many liberties with its source material. Put a different title on either of these and any connection instantly vanishes.

So that brings us to the big question: when does an adaptation simply stop being an adaption? This isn’t like The Hunger Games or Gone Girl, where a film adaptation is forced to cut corners to fit into a new shape. This is an adaptation in name only. It stopped being an adaption a long time ago and its connection to its source material is like an anchor. Being forced to exist alongside each other forces this comparison.

In the book, Hugh Glass’ thirst for vengeance is driven by the fact that two men robbed him on his deathbed and he wants his valuable rifle, and his basic dignity, back. In the movie, Iñárritu and Smith give Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio) a half-Native American son who gets murdered before his dying eyes by the racist Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy). In the book, Glass retreats to civilization to mend his wounds, resupply, and set out in search of the men who left him for dead. In the movie, he wanders aimlessly through the wilderness, experiencing dream, Terrence Mallick-lite flashbacks to happier times, eventually happening across his target. The book climaxes in a courtroom. The movie climaxes with two men engaged in a knife fight to the death in a snowy clearing. Characters based on real historical figures who went on to have long lives and careers meet grisly ends in the movie, which makes the already loose connection to the book’s already loose “true story” genuinely hilarious.

That’s just the tip of the iceberg – every single set piece in The Revenant was invented for the film…which is strange, since the book has a shootout or a fight every few pages. The novel is not wanting for action – it’s a tall tale in longform, a bigger-than-life western adventure filled with grit and excitement.

What did Iñárritu see in this book? Why would he devote so much of his life to transforming a novel that he obviously had little interest in adapting? You have to wonder how Punke feels about the finished film – flattered that a major filmmaker used his book as a jumping off point for a passion project or annoyed that he literally threw away everything that makes the book what it is.

What’s perhaps most surprising about the changes made to the film version of The Revenant is how it takes an offbeat and unique tale of revenge and survival and transforms it into something familiar and painfully Hollywood. Despite his artistic pretensions. Iñárritu has made a painfully straightforward movie. The Revenant movie is arthouse Michael Bay: style and substance in service of the most pat story concepts imaginable. “Revenge poisons the soul” The Revenant all-but-says-out-loud in its grandiose climax. The messy murkiness of the novel, where the reasons for Glass’ revenge are so low key and personal and downright strange, is haunting because it forces the reader to connect with a hero whose mission seems so extreme. By tossing in that plot device of a son, Iñárritu and Smith have taken the easy way out. For a movie that is otherwise unafraid of being as off-putting, intense, and brutal as possible, it’s such an odd choice. It’s such a Hollywood choice.

At least The Revenant cops to the fact that it’s barely an adaption. That “based in part on” credit makes its sins as an adaptation more forgivable. But it doesn’t make it any less baffling. As The Revenant marches toward the Oscar season looking like a serious contender, its inevitable inclusion in the adapted screenplay discussion is about as unpleasant as biting into a raw bison liver.

More From ScreenCrush