Why Do We Still Love the ‘Die Hard’ Formula?

Over the last 30 years, the terrorists of the world have repeatedly found new ways to torment and intimidate the planet.

In that same span of time, the terrorists of the movies have remained steadfastly loyal — some might say foolishly loyal — to one single plan: Take over a location and then hold it hostage for ransom and/or political gain, preparing for any and all eventualities … except one man.

We might call this “the Die Hard plan.”

The list of new movie subgenres that have been created in the last 30 years is surprisingly short. There’s the found-footage horror movie typified by The Blair Witch Project, and the young adult dystopia movie sparked by The Hunger Games. Depending on the looseness of your definition of the word “subgenre,” there’s also the video game movie. And then there’s the “Die Hard in a…” movie, which has, quite improbably, become one of the most popular and populated subgenres of the last three decades of American movies.

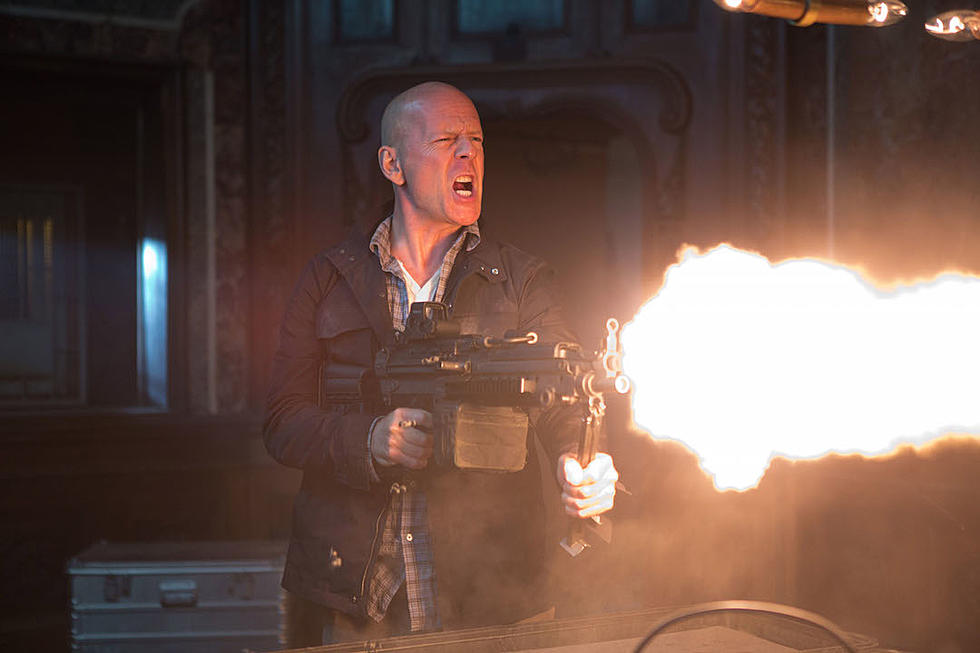

28 years after John McClane (Bruce Willis) first saved Los Angeles’ Nakatomi Plaza and his estranged wife Holly (Bonnie Bedelia) from Hans Gruber (the late Alan Rickman) and his ruthless Teutonic brigade, film bad guys are still finding new places to take hostage (or recycling old ones) while unlikely heroes keep finding miraculous ways to defeat them. This week, movie theaters around the country will host London Has Fallen, the sequel to 2013’s Olympus Has Fallen (aka “Die Hard in the White House”), in which a former Secret Service agent (Gerard Butler) races to the rescue of the President of the United States (Aaron Eckhart) after the Oval Office is infiltrated by North Korean militants.

That was the first Die Hard in the White House in 2013, but not the last; White House Down, starring Channing Tatum and Jamie Foxx as Gerard Butler and Aaron Eckhart, followed a few months later. Those weren’t the only times a fictional U.S. President got mixed up in a Die Hard plan, either. In 1997, Harrison Ford’s James Marshall rescued his family and crew from Russian nationalists aboard Air Force One. And Ford was far from the only action star of the era to turn a Die Hard plan into a hit. Sylvester Stallone did (Cliffhanger, aka “Die Hard on a mountain”). So did Jean Claude Van-Damme (Sudden Death, aka “Die Hard at Game 7 of the Stanley Cup Finals”). Almost all of Steven Seagal’s hits featured Die Hard plans, including the highest grossing movie of his career, Under Siege (aka “Die Hard on a battleship”), and its sequel, Under Siege 2: Dark Territory (aka “Die Hard on a train”).

Die Hard plan movies have been so dependably popular that they’ve actually made actors into action stars. That’s what happened to Keanu Reeves when he made Speed (aka “Die Hard on a bus”), and to Nicolas Cage when he made The Rock (aka “Die Hard on Alcatraz”). At times, it seemed like you plug almost anyone into this scenario, and come out with a hit. There are so many of these movies that there’s a whole Wikia dedicated to what it calls the “Die Hard scenario.” Though some of the movies mentioned bear more Die Hard influence than others, the list of legitimate copycats runs well into the hundreds.

While “Die Hard in a…” movies tapered off a bit around the turn of the century, the subgenre (wait for it) died hard. In recent years it’s made a comeback with (wait for it again) a vengeance. In addition to the dueling Die Hards in the White House (and several actual Die Hard sequels, albeit ones that strayed from the blueprint of the original), we’ve also seen the Die Hard template put into action in an Indonesian high-rise (The Raid: Redemption), a dystopian high-rise (Dredd), and even a space jail (Space Jail, known in some territories as Lockout).

The popularity of Die Hard knockoffs is indisputable. But why does this formula endure? How many times can you watch a bunch of terrorists take a plane hostage only to see their schemes laid to waste by a couple of plucky underdogs? Based on the box office performance of Passenger 57, Con Air, Executive Decision, and, of course Die Hard 2, the answer is it seems, a hell of a lot.

A few years ago, The New York Times Magazine’s Adam Sternbergh wrote a piece on “The Enduring Appeal of Die Hard.” Despite its title, Sternberg’s essay was more about the enduring appeal of John McClane, and how he remained an essential action hero even as his adventures grew completely inessential. In contrast to the cartoonish muscle men that dominated the rest of ’80s action cinema, McClane, Sternbergh says, was all too human:

“Desperate, beleaguered, cornered, aggrieved, battered, frustrated, fed up: Put that way, is it any wonder the character of McClane has persevered? …All those heroes who once stood for certainty, fearlessness and unwavering confidence have been swept away … The one still standing is the one who represents fear, anxiety, frustration, uncertainty and, despite it all, irrational hope.”

Sternbergh’s take on McClane is exactly right, but it doesn’t account for the enduring appeal of the Die Hard formula, at least not entirely. Although some of these Die Hard knockoffs have John McClane knockoffs as their heroes, none possess what Sternbergh describes as the core of McClane’s appeal: his Bruce Willis-ness. (He quotes Die Hard director John McTiernan, who says the character was “built out of Bruce,” i.e. loosely inspired by the actor’s own biography and tailored to suit his strengths as a leading man.)

No “Die Hard in a…” movie has Bruce Willis; few have stars as charismatic (or even half as charismatic) as Willis in his prime. Yet the Die Hard formula thrives without Willis or McClane; many Die Hard knockoffs have outperformed legitimate Die Hard sequels (and even the original movie) at the box office. Paul Blart: Mall Cop (aka “Die Hard in a mall”) more than doubled A Good Day to Die Hard’s domestic take, and none of the Die Hards made half as much money in theaters as Home Alone (aka “Die Hard in a suburban house with a kid”). People definitely love Bruce Willis and John McClane. But they love the formula around him just as much.

That formula was invented by author Roderick Thorpe, who in 1979 wrote the novel Nothing Lasts Forever as a sequel to a previous novel, 1966’s The Detective. Thorpe’s book follows retired NYPD Detective Joe Leland as he attempts to save his daughter Stephanie Gennaro from terrorists (led by Anton Gruber) who’ve taken control of the Klaxon Oil building in Los Angeles. Hollywood previously adapted The Detective into a movie starring Frank Sinatra, and Thorpe hoped Sinatra might reprise the Leland role in a Nothing Lasts Forever film. Sinatra passed on the movie, though, and later so did Arnold Schwarzenegger. (Producers had proposed they reconfigure the project as a sequel to his movie Commando.) Eventually it was decided to make Nothing Lasts Forever a standalone story, and to cast Willis as a new hero. Although a lot of the specifics were added or embellished by John McTiernan and screenwriters Steven E. de Souza and Jeb Stuart, Die Hard’s general outline (and even some details, like McClane going barefoot and leaping from the building’s roof) originated in Thorpe’s novel.

What Thorpe, McTiernan, de Souza, and Stuart created was an irresistible premise for action and suspense, one whose appeal stems from its construction out of a few seemingly contradictory elements. Viewers love John McClane, supposedly, because he’s an Everyman, and to a certain extent that is true. He doesn’t have Arnold Schwarzenegger’s physique or John Wayne’s stoicism or Sylvester Stallone’s indomitable hairline, and over the course of the movie he bleeds quarts of blood and howls in agony and rage. But he’s still not quite an Everyman. He’s also a tough-as-hell New York cop. He knows how to use a gun and explosives. He improvises a bungee cord out of a fire hose, jumps from the top of a skyscraper, and lives.

This is not what every man would do in this situation. Most people in McClane’s shoes (or bare feet) wouldn’t hide in the empty floors of Nakatomi and start picking off Hans Gruber’s men. They would run for their f—ing lives.

But McClane can’t run, and therein lies the contradiction that makes the whole thing work: You have a guy thrown by total accident into an insane situation, who also has a very direct investment in that insane situation’s outcome. McClane isn’t a cop on a case or a soldier sent on a mission. He might make a living as a police officer, but saving Nakatomi Plaza isn’t his job. His arrival at the same time as the terrorists is a matter of sheer coincidence. It has nothing to do with him — or it wouldn’t if his wife wasn’t a hostage.

This sort of thing could happen to anyone, and while we might not have the skills to do what John McClane does, we like to believe that if a loved one was trapped, we would at least try to do whatever we could to save them. This combination of random chance and enormous personal stakes is what makes the scenario perfect from an audience identification perspective. It’s an oxymoronic phrase, but it’s true: John McClane (and really the hero of every Die Hard knockoff) is the ultimate Everyman. He’s simultaneously relatable and aspirational.

There are other elements that make the Die Hard scenario popular, particularly their heroes’ disobedient and rebellious spirits, which tends to put them at odds with authority while placing them in a long tradition of maverick heroes in American fiction that dates back hundreds of years. (They’re modern cowboys, a comparison Die Hard explicitly makes with in its famous “Yippee ki yay, mother f—er” scene.) Hollywood likes these movies not only because of the money they make, but because of their relatively simple productions. Unlike the sprawling scope and budgets of most blockbusters, Die Hard plots are typically confined to a single location and a handful of characters. They’re not necessarily easy to make, but they’re easier than a superhero movie or a Transformers.

Still, it’s that combination of serendipity and firsthand motivation that remains key to the Die Hard formula’s longevity. That’s what allows an audience to indulge in a fantasy where an ordinary guy with the proper inspiration can, at least temporarily, transform into a superhero. After all these years, the fact that terrorists keep going back to this well onscreen is comforting in a weird way as well. The real world is scary enough. It’s nice to imagine a place where sadistic evildoers can be stopped by one guy with a stiff moral compass and a lot of guts. He doesn’t even need shoes.

More From ScreenCrush