‘Bridge of Spies’ Review: Master Spies From Master Filmmaker Steven Spielberg

Naysayers will describe Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies as “old-fashioned.” They have a point; the film is long, deliberately paced, and visually low-key. But sometimes old-fashioned aesthetics are the only way to tell a story about old-fashioned values — and to show that both still have their place in 2015.

With Bridge of Spies, Spielberg continues the project he started with Lincoln: Using history to illuminate his personal vision of American heroism. But where Lincoln was about a “great man,” Bridge of Spies is about an ordinary one — an insurance lawyer from Brooklyn named James B. Donovan. In the late 1950s, Donovan was chosen by his peers to represent a captured Soviet spy, Rudolf Abel. But while most of Donovan’s colleagues (and even the presiding judge on the case) want him involved purely to give Abel’s trial the appearance of due process, Donovan actually mounts a rigorous defense of his client, at considerable risk to his reputation and his family’s safety.

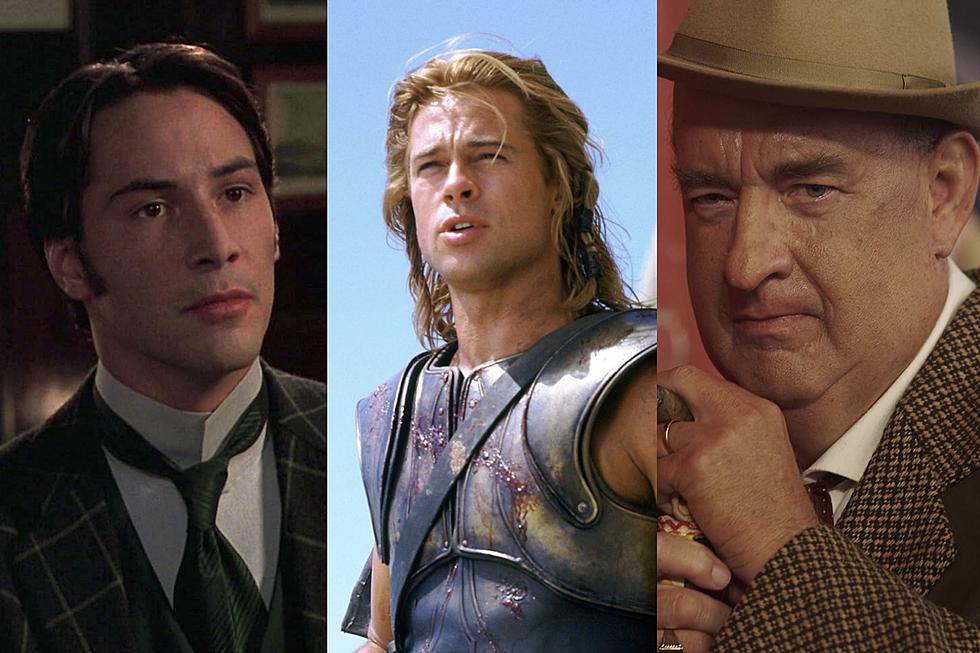

Donovan’s played by Tom Hanks, and if this isn’t Hanks’ greatest performance, it’s certainly his Hanksiest. For 30 years, Hanks has been Hollywood’s foremost emblem of everyman decency. As Donovan, he gets to play perhaps the ultimate expression of those principles — and an American movie hero who warrants comparison to Henry Fonda in 12 Angry Men or James Stewart in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Like Juror #8 or Jefferson Smith, Donovan perseveres; not for glory or greed, but for the radical reason that it is simply the right thing to do.

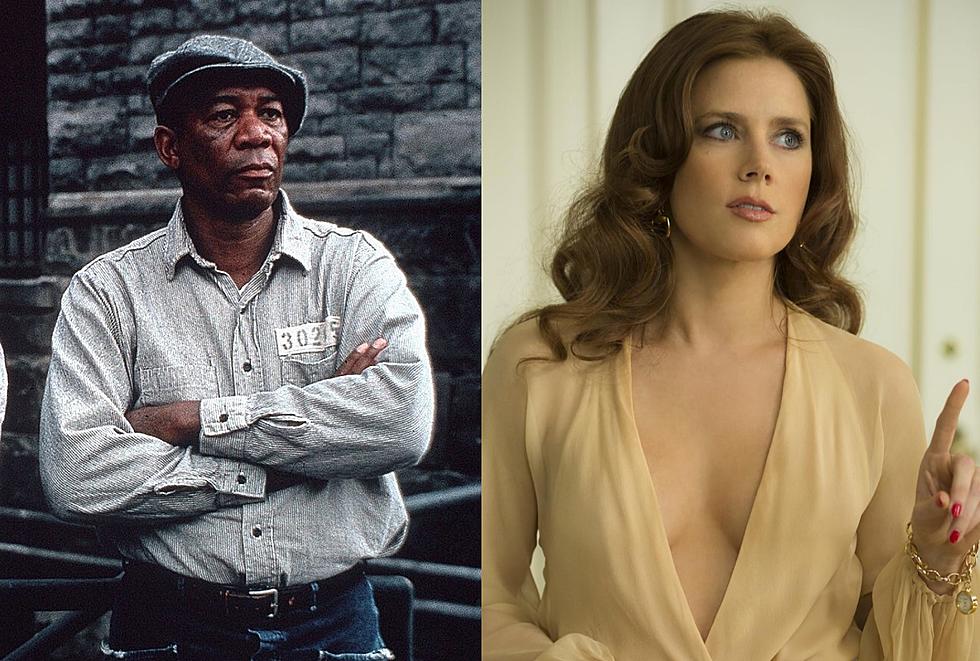

Hanks is matched perfectly by Mark Rylance as Rudolf Abel, a solemn man whose face never betrays any emotion. (He is, after all, a master spy.) He’s America’s enemy but an honorable one, and he forms an unlikely friendship with his attorney. His case isn’t necessarily about guilt or innocence — Spielberg makes Abel’s guilt clear from the very first scene, a wordless, brilliant cat-and-mouse game through the streets and subways of New York City. Instead, it’s about integrity.

Early in the film, Donovan shares a drink with a CIA agent who wants him to hand over any information Abel’s given him about his espionage activities, a clear violation of attorney-client privilege. In refusing, Donovan makes an impassioned argument in favor of “the rulebook.” He’s Irish; the CIA agent’s German. The rulebook (aka the Constitution) is what makes them both Americans. If they ignore that, they’re no different than Abel’s employers, or anyone else who seeks to undermine our democracy. If that sounds corny or maudlin, you might want to skip Bridge of Spies.

In that scene and many others, Hanks is dressed in a dark blue suit with white shirt and red tie; though its hues are muted by Janusz Kamiński’s inky cinematography, Donovan’s literally draped in the colors of the American flag. Scene after scene of Bridge of Spies is filled with smart, subtle details like that one. This is far from Spielberg’s most exciting or dramatic film, but in every single moment you feel like you’re in the hands of an absolute master of the cinematic form, from the lighting to the camera placement to costume and production design to the actors’ comic timing to the magnificent match cuts that connect the various plot threads. Spielberg mostly squanders Amy Ryan in the role of Donovan’s wife Mary (she does have one beautiful scene at the end of the film), but the rest of the supporting cast is outstanding, including Alan Alda as a partner in Donovan’s firm, Peter McRobbie as the head of the CIA, and Sebastian Koch as an East German lawyer.

Many of these characters arrive in the film after American pilot Francis Gary Powers (Austin Stowell) is shot down in the U-2 spy plane over the Soviet Union, and Donovan is recruited to travel to Berlin to arrange an exchange; Abel for Powers. Bridge of Spies’ early ’60s Berlin is an absurd place, populated by eccentric bureaucrats, cheerful secret agents, and roving gangs of street toughs. Many of them feel like refugees from a Coen brothers movie — and lo and behold, Joel and Ethan Coen are credited as the co-writers of Bridge of Spies’ screenplay (along with Matt Charman). The Coens and Spielberg make an ideal combination. Spielberg’s never been afraid of sentiment, and Bridge of Spies has his plenty of it, but the Coen’s snappy, snarky dialogue dilutes some of the earnestness.

Though set in the 1950s and ’60s, Bridge of Spies’ message clearly resonates with modern political issues about privacy, justice, and security. (The words “Edward Snowden” and “National Security Agency” are never spoken in Bridge of Spies, but they are its clear subtext.) The means by which Spielberg argues his case for the rule of law and simply human decency is admittedly laced with a fair amount of schmaltz. But an old Jewish guy like Spielberg knows that in the right situation, schmaltz is absolutely delicious.

More From ScreenCrush