Remembering the Lost Action Hero of the 80s: Dabney Coleman

The chances of you remembering the movie 'Cloak & Dagger' increase significantly if you were born between 1972 and 1976. On the surface, this seems like an oversimplified statement, because a lot of movies are like this. I'm sure there are others, but I was born in between 1972 and 1976, so this is a movie that is very much in my own personal wheelhouse, yet it's also one that gets the most amount of blank stares when referenced in front of other people who do not fit this age criteria. (Followed closely by 'Max Dugan Returns.')

It's an almost-strange phenomena that shouldn't be "strange," because 'Cloak and Dagger' is a throwaway movie, yet so many throwaway movies—especially from the ’80s—are still very much a part of our culture today. People have not let them die, yet 'Cloak and Dagger'—a fairly popular movie after it was released (due more to endless replays on premium cable than its initial box office run, which started as a double feature with 'The Last Starfighter,' of all things)—is dead. And I am not at all arguing for its resurrection. In fact, I hadn't seen 'Cloak and Dagger' in maybe 30 years until I saw it pop up on one of those “these movies will be disappearing from Netflix” lists a couple of weeks ago.

It's a weird thing, watching a movie only once as a child, then watching it again as an adult. There are not many examples left that qualify. Watching 'Back to the Future' today doesn't count because I've seen it so many times in between. Before I re-watched 'Cloak and Dagger,' from what I remembered, my description of this movie would have been:

A young boy goes on an adventure with his totally real friend, Jack Flack, a super spy who just coincidentally looks a lot like the young boy's father (and a lot like Dabney Coleman).

And watching today, I kind of felt sorry for my 10-year-old self for thinking that, because Jack Flack is so obviously (well, mostly, more on that later) a figment of Davey Osborne's imagination. (And I'm sure my 10-year-old self currently feels sorry for me; he's probably right.) More than anything, 'Cloak and Dagger' is a story about imagination, and I suppose it had its desired effect on both children and adults: children believed in Jack Flack and adults didn't. I suppose it's much more fun to believe.

Davey Osborne (Henry Thomas) has an active imagination and often finds himself acting out “spy missions” with his friend, Kim (Christina Nigra), who seems to think that Davey is a bit of a dolt, but at least finds him interesting. Also along for the ride is a superspy named Jack Flack (Coleman), who never really does anything that would require him to interact with other human beings, but he does often give Davey terrible advice.

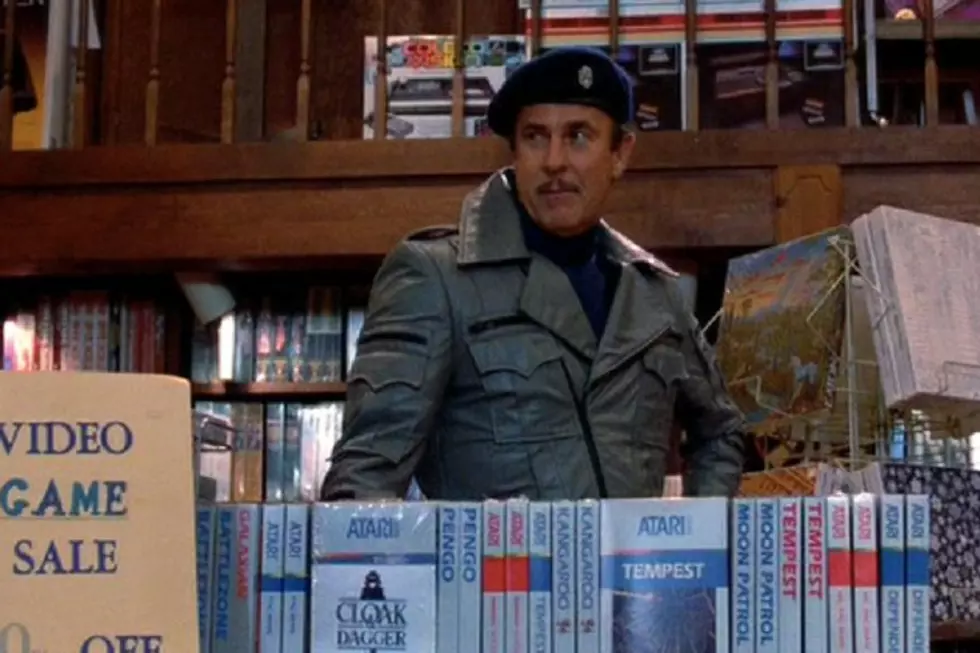

One day, while on a fake "mission," a scientist of some kind hands Davey an Atari 2600 cartridge titled 'Cloak and Dagger'—which (a) is genius cross-promotion in that the video game is actually central to the film's plot and (b) is strange, because throughout the movie the video game is referred to as a "tape"—that holds a special chip containing government secrets. Coming as no surprise to anyone, no one believes Davey, so it's pretty much just him and his imaginary friend as they avoid what are really hapless and incompetent henchmen.

For the life of me, I couldn't remember that the central MacGuffin of 'Cloak and Dagger' was an Atari 2600 video-game cartridge. There's even a lengthy scene in which Davey plays 'Cloak and Dagger' in an effort to discover its clues (as it turns out, the "tape" had to be opened up to find the mystery file). As this scene plays out, Dabney Coleman is just sitting there watching this game be played. I couldn't help but wonder what Dabney Coleman was thinking as this scene was being filmed. (I often wonder what Dabney Coleman thinks about in general.)

Like a lot of people my age, my first introduction to Dabney Coleman was for his role as Jonathan Hart in the immensely rewatchable '9 to 5.' There always been something gruff about Coleman's performances, but there's also a strange warmth. These traits fit Jack Flack more perfectly than it seems like they should. After '9 to 5,' Coleman made a career of being the prickly authority figure in movies like 'Tootsie,' 'WarGames,' and 'The Man With One Red Shoe.' After rewatching 'Cloak and Dagger,' it's now kind of surprising Coleman didn't do more roles that shows off his more tender side. He's good as Jack Flack, but he's surprisingly great as Davey's father, Hal Osborne. Once Hal realizes that his son has been telling the truth, I found myself getting emotional—as in, I knew Hal would save the day because this is Dabney Coleman and you don't fuck around with Dabney Coleman.

There's a scene near the end of 'Cloak and Dagger' in which Jack Flack sacrifices himself to save Davey. To do this, Jack Flack materializes enough so that the villain can see Jack; this distracts the villain long enough for Davey to eventually shoot and kill the villain (in a scene that would never, ever be in a movie geared toward kids today). Here is where I reached an understanding with my 10-year-old self. It's this scene that created enough ambiguity that I decided at the time that Jack Flack was real. And it is a confusing scene and I'm still not entirely sure how to interpret it, and it seems like a fool's errand to spend a significant amount of time trying to decipher the deeper meaning behind 'Cloak and Dagger.' (Then again, I've just written a full piece about 'Cloak and Dagger' so I'm not sure another 200 words about its meaning would make this any more ridiculous; stay tuned next week for my thoughts on the deeper meaning of 'Max Dugan Returns.')

I'm not going to pretend there was anything meaningful to come from this experience—that I somehow unlocked long-repressed feelings or memories thanks to Jack Flack. But I did at least enjoy the experience of trying to remember why 'Cloak and Dagger' was at one point something that I liked. 'Cloak and Dagger' is not a bad movie by any means, but it's not as fun knowing, through common sense, that Jack Flack was a figment of Davey's imagination.

As Jack Flack lay dying, filled with bullet holes and bleeding profusely (again: the ’80s!), he tells Davey that he appeared to the villain because apparently the villain still had some imagination left. I suspect, in this same scenario, I wouldn't see Jack Flack. But I like being reminded that I once would have.

Mike Ryan has written for The Huffington Post, Wired, Vanity Fair and GQ. He is the senior editor of ScreenCrush. You can contact him directly on Twitter.

More From ScreenCrush