Emmanuel Lubezki on ‘The Revenant,’ ‘Knight of Cups’ and the Importance of Breaking Rules

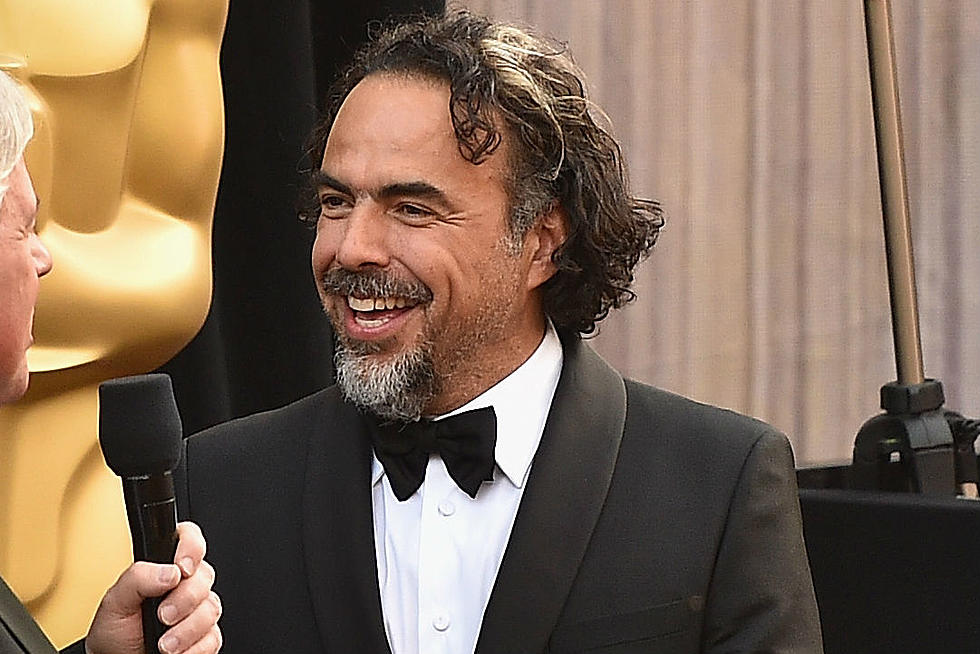

Emmanuel Lubezki just won his third Academy Award, making history as the first person to win the Oscar for Best Cinematography three years in a row. Following Gravity and Birdman, Lubezki won for Alejandro Iñarritu‘s The Revenant at the 2016 Oscars, Lubezki is now one of the most celebrated cinematographers of all time.

Lubezki has long dazzled audiences with his immersive style of photography, most notably the single takes of Y Tu Mamá También and Children of Men, and the majestic, natural imagery of The New World and The Tree of Life. Many of those signature techniques are in full effect in his latest films, The Revenant and Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups, which showcase Lubezki at his most dynamic, most experimental and most daring. While Birdman took on the major task of appearing to be one long take, Lubezki’s latest collaboration with Iñarritu is already famously known for its controversial shoot. While catching up with the 51-year-old Mexican cinematographer a few weeks ago, Lubezki told me about making the Leonardo DiCaprio survival epic, which taught him how to be “a little bit like an athlete.”

Environmental challenges aside, Lubezki talked about his process of capturing the different moods of intensity and tranquility in The Revenant, the “most difficult film” he’s ever made, and a cut scene that included a monster. The cinematographer also discussed his work on Knight of Cups, a film he shot without ever reading the script, and the experimental methods of his latest two Malick collaborations.

What would say was the most difficult scene or shot to pull off for The Revenant?

You know what was very hard? We shot one scene in the very, very top of a mountain. We had to take these things called the Skidoos, those motorcycles for the snow. Everything had to go in Skidoos, and we have lets say eight Skidoos for fifty people. It was exhausting just to be in the Skidoos for 45 minutes up to a mountain, and then when you arrive at the mountain you’re past 8,000 feet. So you get tired. Very, very tired. […] And that is one of the scenes where [Hugh Glass] finds that Captain Henry was killed by Fitzgerald. And he looks up and you see the snow coming down on the side of the mountain. That was very hard for the crew. A lot of people had to go down [the mountain]. And then one of the days that we were shooting there, as soon as the sun set we started seeing an Aurora Borealis, and it was the first time I’d seen an Aurora. It was like a gift. It was like, “You guys survived, now you can see this beautiful Aurora Borealis.” It was an amazing present.

The film has many intense moments, but there’s also some tranquil, quiet ones, especially in the dream sequences. Did you have different approaches to creating those moods, or did that naturally come about while shooting?

We did a lot of tests as we were shooting because we didn’t know how to shoot the oneiric part of the movie, the flashbacks and the dreams. For instance, we wanted to do something really stylized and we tried it and we failed. That’s something I love about working with Alejandro, if he feels that it’s not right he will redo it or he will not put it in the movie. That frees you as a collaborator, a craftsman, to try all sorts of things including incredibly insane stuff. We even shot a scene with a monster and things like that that almost felt wrong, they didn’t feel like they were a part of this movie, or that the tone was right, or the tempo was the wrong tempo. Little by little we realized that if the cinematography was exactly the same as the rest of the movie, in terms of using the same lenses and the same camera angles and everything – if I kept the cinematography very naturalistic, that Alejandro was able to build on top of that a layer of a more, like magical realism, or another level of realism that is not naturalistic. And that it would not be shocking and it will feel like the same movie and it will be as immersive as the rest of the film. So while doing all these tests I used the same techniques. But because we shot most of the flashbacks in California, they do have a different feel because the lighting is different, the terrain is different, there’s more warmth in the light [since] we did it closer to the summertime.

That’s interesting you say magical realism because –

Well that’s because I couldn’t find another word. I’m not even sure what magical realism is. But I was trying to say it’s just another level of realism that is not as naturalistic.

A lot of those dream sequence moments reminded me of Tarkovsky.

Thank you. Thank is very kind, oh my gosh! That’s a tall order.

Well a few of the images strongly recall his work, especially Glass’ levitating wife which feels like an allusion to The Mirror. Was his work something that was on your mind at the time?

One thing that is important to say is that we didn’t see any other movies as references for the movie. So if some of the images feel close to the work of other authors, it’s because we felt that those images were very iconic somehow. I guess that Tarkovsky felt the same thing when he used images that were like that. But we didn’t go to his movies to try to get influence. I probably heard Alejandro talking about Tarkovsky with [production designer] Jack Fisk at one point, but I was really trying to avoid any film references. I was trying to find the language that was correct for this particular movie as opposed to doing some film homage. When we shot the woman with the bird, when the mother dies and the bird comes out of her chest, I did laugh to Alejandro when he told me that idea. I said, “Man that feels familiar.” But that’s the only thing I said, we didn’t talk more about it. I don’t know exactly how that image came to him, but it has to do with many things. It’s an iconic image of a soul leaving a body or something like that. Maybe not, maybe he’s thinking about something else, but that’s what it felt [like] to me.

There was a lot of rehearsal for the film, but also a lot of improvisation as well, is that right?

Yes, that’s right. The main preferred methodology was to rehearse, especially for all the long complex scenes, the first attack or the bear attack or the horse falling from the cliff or Leo [DiCaprio] coming out of the horse. So the ones that are technically challenging, Alejandro wanted to rehearse. Even the first shot of the movie when the camera is looking down to the water and you see this forest that is inundated with water. The presentation of Glass, all that was not improvised, was very rehearsed. Then there were other moments when we finished the work of the day [on] one of these complex scenes and there was still light, we would play with Leo, with other actors that were around. Beautiful scenes like the scene between Leo and Arthur [RedCloud] when they are eating the snow and they laugh, that came from a little moment of improvisation. That scene was written in the script, but it was written very different. When we attempted to shoot it we failed because there was no snow. One day after finishing the main scene of that day, it was snowing and the scenery looked incredible and mysterious so we said, “Why don’t we try that scene?” Leo and Arthur have this improvisation and we just shot it. But a lot of little moments are improvised.

Improvisation and shooting during “the magic hour” are things you’ve done a lot with Terrence Malick. Had your work with him prepared you in any way for working on The Revenant?

A lot of people are asking me if there are similarities between Terry and Alejandro and I would say that they are incredibly different, almost opposite. The thing that they have in common is that they are true filmmakers and they express their ideas and emotions through film. What they are trying to do is not literature, is not theater, not music, not architecture, it’s a very cinematographic art. They are both authors and in that sense they are similar. But the way they use the camera and the way they express themselves are very different. But yes, working with Terry prepared me, and working with [Alfonso] Cuarón, and with Rodrigo [García] and with Tim Burton, and all the directors I’ve worked with prepared me to do this movie that has to be the most difficult movie I’ve done. I think some of the Terry DNA must have come out because I’m his pupil, he’s my teacher. I can see little things from Terry and Cuarón and all these directors I’ve worked with. Every time you work with a director that is good, you learn you absorb and these things just come out.

When working on The New World you and Malick created a dogma of filmmaking rules. Do you have that with each director you work with or do you have your own?

I realize now thinking a posteriori, not during the shoot, I realize that in every movie I’ve worked [on] since I started, since probably film school, I create a set of rules. Maybe it’s the same thing that all the filmmakers, in terms of, you have to create your own set of limitations. Because the language is limitless, so if you don’t have a set of limitations, first it’s very hard to make any decisions. When you see a film there’s so many ways you can approach it. So if you have a set of these rules it allows you to make decisions easier. It’s obviously dangerous because once you make a set of decisions, if it’s the wrong decision the movie is not going to work, but not all movies work. But I realized that I always work with a set of limitations. Terry liked that as well and it was a way for him to express how he wanted to do the movie and to explain to me the tone of doing the movie and what kind of equipment he wanted to use for the movie. But we always have what he calls “Article B,” that is “except, except, except when.” It’s an exceptions and that means you should always allow your films to break the rules you’ve created. That’s very, very important. And we did it in Revenant many, many times. Because if you don’t vary, if you don’t change the movie’s not going to breathe and it’s not going to feel human.

To me that ability to change and break rules feels inherent to Knight of Cups, which is much more abstract and fluid than your previous work with Malick. How do you think your work together has evolved?

That was incredible for me and in a way very experimental. Terry came to me and he said, “Chivo, please don’t read the script.” The script was very, very long. He had probably 400 pages, or six [hundred] or five [hundred], I don’t know. He’s a very prolific writer. He said, “I would like you not to read the script and approach the scenes a little but like a documentary filmmaker, but it’s not a documentary filmmaker that is documenting the external.” He wanted me to document this as if it was somebody’s memory. That’s it, we never talked about anything else. The movie wanted to be very fragmented and wanted to feel a little but like a memory, like an experiential movie. Like the zigzagging, he wanted to feel the zigzagging of being there and remembering something, how I’m talking to you but at the same time I’m looking at my daughter’s bedroom and I’m looking at the light in the hallway as I walk around. It’s how we are in one place, but the reality can be almost cubist as you’re living it. That’s the way I wanted the movie to feel.

Had you ever done that before, where you don’t read a script before shooting?

No, no. I’ve never done that, with anybody. In film school they teach you that the first thing you have to do is learn the script – they almost teach you that cinematography is the translation of that script into image, which I think is not true in the case of almost any movie, unless you’re using cinematography to only do straight dialogue. But in the case of these great directors, they don’t use cinematography to do straight dialogue, they use photography to express emotion, to express feelings and to immerse the audience in a world. That’s why I like working with these guys. I’ve never done a movie like this. But it was a lot of fun, and scary because when you’re shooting you don’t know if you’re missing the point of the scene. The only way I have to know if we’re getting the scene or not, I’d turn sometimes to Terry and see if I could get a feeling from his expression.

Do you know in the moment if you’ve got the shot?

No. We attempt the scenes sometimes in many, in different locations and places. So let’s say there’s a fight between the main character and the ex-wife. So we try it outside their former house, or we try it in an airport, or we try it in different places until Terry feels that it feels like a memory, if it’s expressing the feeling he’s trying to get. When I saw the movie, something that was incredible for me – I didn’t know the script, I was putting together the pieces as I was shooting. It felt to me like a movie made by a very young director, somebody very completely fearless and again, [who’s] trying to use the medium in a very, I wouldn’t say pure, but in a very cinematic way. It’s not theater, it is not any other art but film. That was very exciting. I really loved the movie.

That’s interesting you say it feels like it’s from a younger filmmaker while this is so much later in his career. Do you think Knight of Cups represents a different era of his work, or a new process?

That only tells me how incredible Terry is, because he’s so daring. This is a crazy experiment in a way – not crazy, I wouldn’t say crazy. It’s a wonderful experiment. And trying to use film in this way, it has nothing to do with the mass-produced film that we get from most studios. This is a very different kind of film.

Was your approach similar on your next project together, Weightless?

Those two films that we did back-to-back, you could say they were similar in that respect. I didn’t read the script. We were like guerrilla attack. We were right in a location and we would shoot the scene – the actors knew the scene, I don’t know how much they knew about their character, my guess is a lot because Terry talked to them for many months before we shot. Terry would have a menu, we called it. The menu included a lot of scenes he wanted to shoot in one day. He would attempt a lot of them, not necessarily all of them, and the scenes could be reshot another day. We shoot so fast that we could shoot a movie in one week. Then that menu would have also a whole menu of locations that Jack [Fisk] would suggest to us. He broke the map of Los Angeles in different parts and we would say, “Okay, today we’re shooting in Venice, Santa Monica” then we would take the scenes he thought were right in those locations and we would drive in these vans and just shoot, shoot, shoot, shoot all of these scenes. Then we did Downtown, the airport, different areas. He had different scenes for the different moods and feelings he wanted to capture.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Knight of Cups is in select theaters now.

More From ScreenCrush