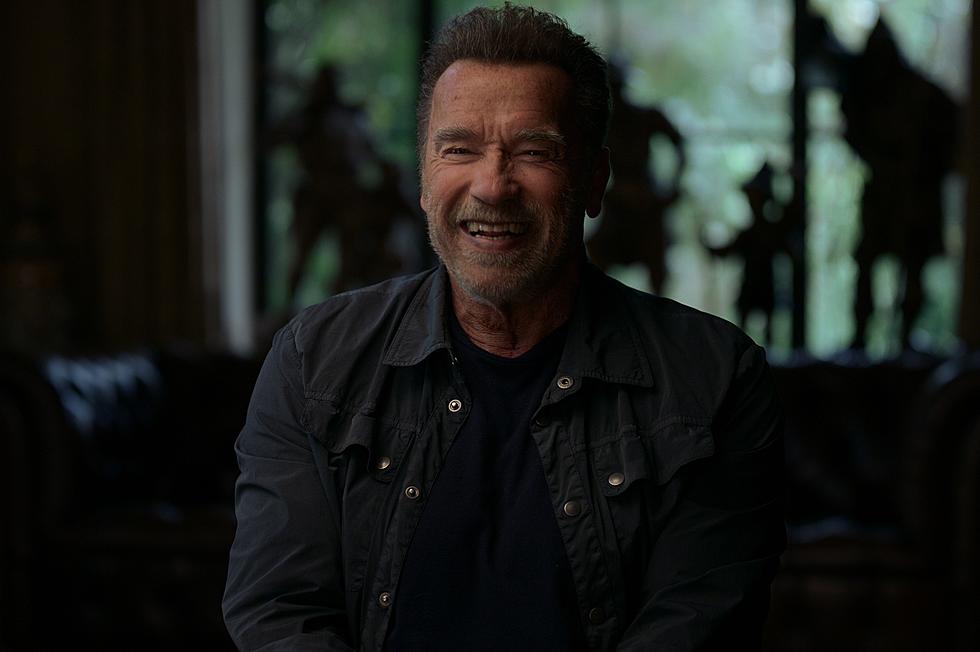

‘Maggie’ Review: The Softer, Sadder Side of Arnold Schwarzenegger

For Arnold Schwarzenegger, killing has always been easy.

Through most of Schwarzenegger’s film career, whatever his character’s stated profession — retired army commando, undercover FBI agent, super spy — his unspoken profession was unstoppable murderer. It was his job, and he took pride in it. Pleasure, too; killing was so effortless and uncomplicated for ’80s-era Schwarzenegger that he cracked jokes while he did it. All that changes in Maggie, in which Schwarzenegger’s character can’t bring himself to kill a single person, one he cares deeply about: His daughter Maggie (Abigail Breslin), who’s been infected with a slow-acting zombie virus.

When Maggie succumbs to the virus, Schwarzenegger’s Wade Vogel will have to decide whether to bring her to a quarantine zone (and effectively abandon her), give her a cocktail of medication that will kill her slowly and painfully, or to put her out of her misery quickly with a bullet to the brain. For any father, this would be an impossible choice, but it’s a particularly novel one to consider through the eyes of Schwarzenegger, who was once the cinema’s most simplistic killing machine but has, in recent years, preferred projects that weigh the moral and emotional costs of the kinds of violence he used to laugh about.

There’s really not much more to Maggie than that; it’s a small, simple horror drama about a family struggling to survive in the midst of a “necroambulist virus” outbreak that slowly and cruelly leaches the infected of their humanity until they finally turn into a flesh-craving zombie. Previous zombie films have tortured their heroes by making them confront undead loved ones, but Maggie twists the formula by turning the walking dead into a metaphor for Euthanasia. Wade knows his daughter’s condition is fatal, and that nothing can be done to save her. But he promised his late wife he would protect Maggie, and he can’t conceive of ending her life, even if that would also mean ending her suffering.

That leads to many shots of Schwarzenegger wandering through his fallow Midwestern farm, gravely searching the horizon for answers and even shedding the occasional manly tear. This, too, is a major departure for Schwarzenegger, who smokes no stogies, cracks very few smiles, and delivers no one-liners. Schwarzenegger isn’t Olivier, but after forty years in front of the camera, he knows how to play to his strengths as an actor. Furrowing his brow and narrowing his eyes, he’s a powerful, solemn onscreen presence. Schwarzenegger is a father himself, and a guy who’s made his fair share of mistakes in his private life. It’s not for me to say if that’s where he drew on the feelings of guilt, regret, and sadness he brings to the surface as Wade. But whatever he used as motivation, it worked. It’s a good performance.

The main issue with Maggie isn’t Schwarzenegger; it’s the sketchy world around him, which is vague and confusing. If society’s collapsed, why are there still working hospitals and active police officers? At one point, a cop tells Wade, who refuses to turn Maggie over to authorities, "You and her aren’t the only people in this town!” But as far as we see, they are the only people in this town; perhaps out of fiscal necessity, director Henry Hobson barely ventures beyond Wade’s farm and offers little sense of any wider community beyond its borders.

He also never fully justifies Maggie’s (admittedly gut-wrenching) premise. Even if this necroambulist virus takes several weeks to turn people into zombies, what hospital would release a doomed victim back into the wild? The screenplay by John Scott 3 offers the explanation that a family doctor pulled a few strings, but it seems to be standard policy to hand these ticking zombie time bombs back over to their families, where they can wreak emotional and physical havoc on loved ones and put undue strain on the local cops. It would make a lot more sense to quarantine Maggie immediately, but if they did there’d be no movie.

Maggie would be better with a clearer sense of the rules of this world, and a clearer sense of how long the title character has left before she turns into a zombie. But the central relationship between Schwarzenegger and Breslin is strong. When he was young and still looked like Mr. Universe, Schwarzenegger’s movies were all about strength. He’d carry giant redwood logs on his shoulder or pick up cars with his bare hands, then slaughter entire islands full of terrorists as an encore. Like most of the movies the Governator’s made since his return to Hollywood, Maggie is about weakness. Despite all his past exploits, Schwarzenegger can’t save his daughter from pain, a fact that makes Maggie feel infinitely more tragic than it would with another, less superheroic actor in the paternal role. Now in late middle age, the remnants of Schwarzenegger’s once-massive physique carry with them a certain unavoidable melancholy. After laughing in the face of death for so long, dying doesn’t seem quite so funny any more.

More From ScreenCrush