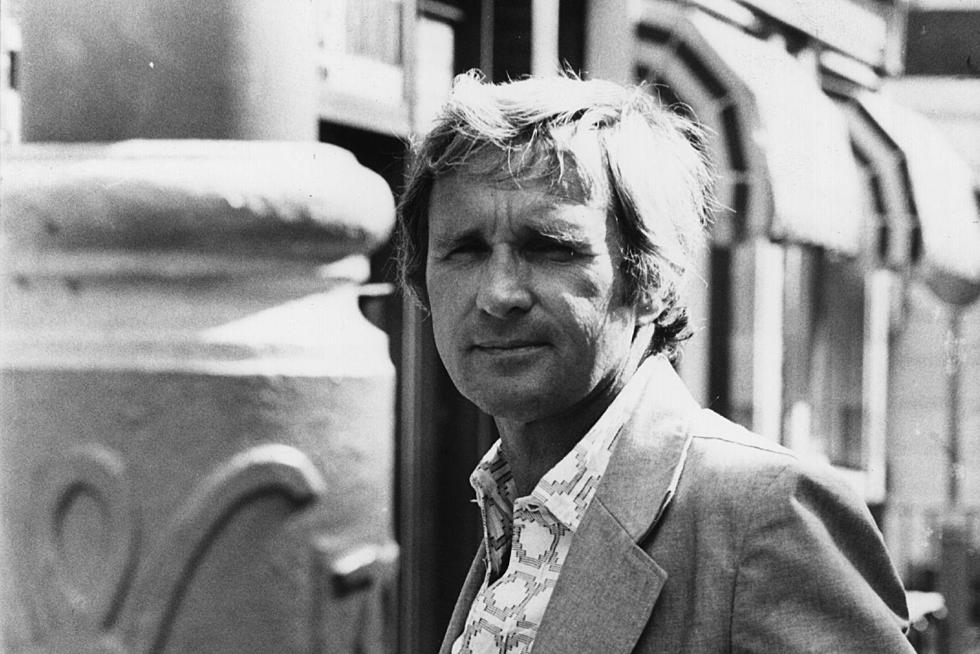

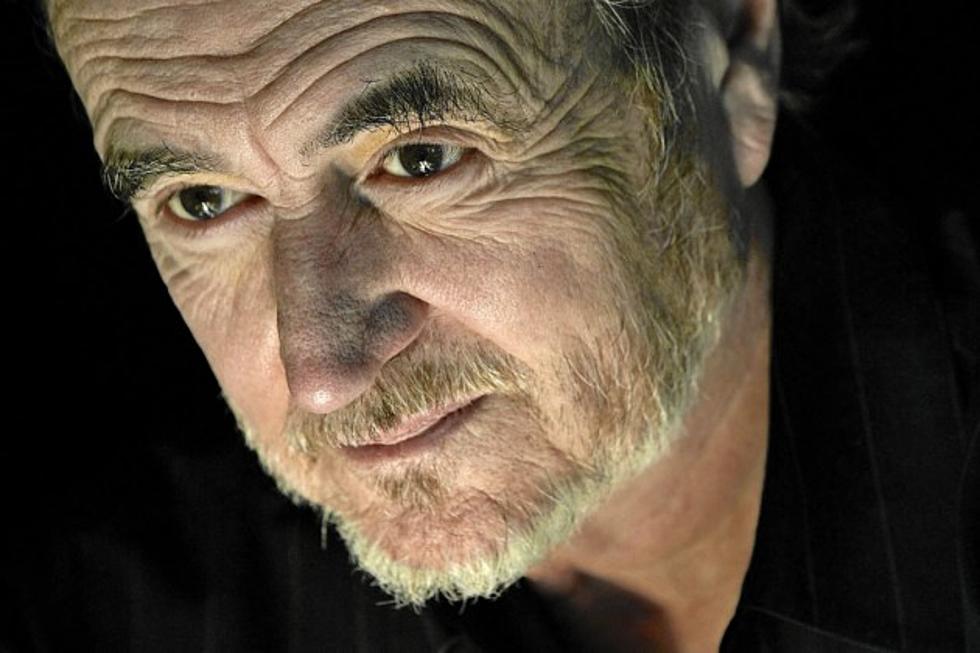

Remembering the Immortal Work of Director Wes Craven

The following piece contains SPOILERS for Scream and A Nightmare on Elm Street.

Movies are fixed. Their meanings are not.

When news broke that Wes Craven, the director of horror classics like A Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream, had passed away yesterday after a battle with brain cancer, I did what a lot of cinephiles do when a filmmaker they admire dies; I watched some of that filmmaker’s movies and reconsidered about their work. The hours after Craven’s death added a whole new context to his filmography, and brought forth a sad theme that runs through many of his movies that I hadn’t noticed before: An obsession with life after death. The man’s most memorable characters almost never rested in peace. Resurrection was such a key part of his films that he even poked fun at the idea in the finale of Scream.

Neve Campbell’s Sidney may have blown away Skeet Ulrich’s Billy, but “Ghostface,” his sinister alter ego, would return to plague her on three separate occasions. And the Scream franchise quickly proved so popular that it essentially resurrected the entire slasher film genre, which had grown stale from too many dumb retreads in the 1980s and ’90s. Scream and its sequels gave the entire horror genre a new lease on life, spawning all kinds of imitators and knock-offs.

In Craven’s filmography, that sort of repeated haunting was not uncommon. His most famous creation, Freddy Krueger, gained his magical powers after he was burned alive by the parents of his victims. From that day on, Krueger (Robert Englund) was the immortal master of the dream world, where he tortured the children of Elm Street for years. In every installment of the franchise, Freddy would die, but never for long.

Nancy (Heather Langenkamp) destroyed Freddy at the climax of Craven’s first Nightmare, but he returned, good as new, a few minutes later, setting a pattern of death and resurrection that would continue for more than a decade. (The sixth film in the series had the doubly inaccurate title Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare.) The Nightmare on Elm Street franchise was so successful (birthing no less than seven sequels, a remake, and a TV series), it practically turned life after death into a Hollywood horror business model.

Craven only directed the first Nightmare and the seventh, Wes Craven’s New Nightmare, a metatextual riff on the concept starring Langenkamp, Englund, and even Craven as themselves in a world where the “death” of the Nightmare saga following The Final Nightmare released Krueger into the “real” world, giving him one more stab at his enemies. As Craven himself describes in a New Nightmare scene with Langenkamp:

The problem comes when the story dies. It happens a lot of different ways, the story gets too familiar, or too watered down by people trying to make it easier to sell, or it’s labeled a threat to society and just plain banned. However it happens, when the story dies, the evil is set free.

Even as a fictional construct, Freddy Krueger found immortality and renewed supernatural power in death.

So did Horace Pinker, the villain of Craven’s 1989 film Shocker, about a serial killer (Mitch Pileggi) whose rampage is abruptly interrupted by a clairvoyant high school football player named Jonathan (Peter Berg). Berg’s policeman father (Michael Murphy) arrests Pinker, who promptly receives the death penalty, but somehow the electric chair turns him into a non-corporeal being of pure electricity who can possess other people and puppeteer them into committing more heinous acts. For Pinker, like Krueger, death is merely the prelude to his sickest crimes, like turning a sweet little girl into the embodiment of evil:

These movies were always scary, but now they’re sad too; Craven’s death adds a melancholic tinge to all of his work. So many of his projects were about an epic struggle between the innocent and the wicked, where the wicked refuse to stay dead while the innocent suffer and perish. (There are more examples one could cite, including some of Craven’s most critically derided projects, like the undead protagonist of Vampire in Brooklyn or the spirit of “The Riverton Ripper” from My Soul to Take that tortures the town’s next generation of kids). Craven is gone now, and unlike Freddy Krueger or Ghostface or Horace Pinker, he’s not coming back.

To watch Craven’s work is to wrestle with a painful and disturbing truth: That darkness is powerful and ever-present. It can be defeated, but only temporarily. If there’s some glimmer of hope, it’s in the way Craven imparts nobility to those that struggle against that darkness. So many of these movies are about naive characters gaining a deeper understand of the world. Heather triumphs in A Nightmare on Elm Street (albeit temporarily) by uncovering her parents’ crimes. Exposing buried secrets is also the key to Sidney’s survival in Scream, and Jonathan’s in Shocker. In Craven’s universe, a hero succeeds not by wiping out iniquity (which is impossible), but in identifying it, facing it, and refusing to turn a blind eye to it.

Craven’s work is a call to arms, to recognize injustice while we still have time to do something about it. Even though Craven was rightfully credited with influencing several decades of horror films through Nightmare and Scream, his wider career as a director and auteur beyond those two franchises has largely been overlooked and unappreciated, partly because he spent most of his time in the disreputable genre of horror. It would only be fitting if critics now decided to explore and herald some of the less respectable corners of Craven’s career; to do justice to a great filmmaker’s life. Movies are fixed. Their reputations are not.

More From ScreenCrush