‘Spectre’ and How the Ghosts of Old Movies Become Bad Twists

This article contains spoilers for Spectre and Star Trek Into Darkness. Don’t read further if you don’t want to know their stupid, stupid twists.

There is a precise moment when Spectre turns to crap.

Before this moment, it is a superbly stylish espionage thriller. After this moment — which can be pinpointed down to the exact shot and lines of dialogue — it falls apart, and its carefully cultivated atmosphere of mystery dissipates like a, well, you know.

This is the moment. James Bond (Daniel Craig), has followed a trail of breadcrumbs from Mexico, where he acquired a mysterious ring stamped with an octopus, to Italy, where he sneaks into a meeting of a special executive organization dedicated to counter-intelligence, terrorism, revenge, and extortion. After a few bureaucratic formalities (hey, even shadowy terrorist groups have ’em), a hush falls over the group and its leader enters. He sits at the far end of the table. He says nothing. The meeting continues. Lit from behind, his face is cloaked in shadows. The air is thick with tension. Bond watches silently from the balcony, anonymous in a sea of Spectre members.

After the introduction of Dave Bautista’s silent henchman Mr. Hinx, the leader speaks, in the unmistakable inflections of Christoph Waltz. Then, without warning, the leader addresses Bond in the balcony. “Welcome James,” he says, as Waltz’s face finally comes into the light. “It’s been a long time.” Bond’s face falls. Waltz continues. “I see you. Cuckoo!”

And that’s it. Bond makes a hasty escape in a hail of gunfire while Hinx gives chase in a fancy sportscar. While he’s driving through the streets of Rome, Bond puts a call in to faithful Moneypenny (Naomie Harris), and asks her to hunt down several leads. One is for “The Pale King,” a name he’s heard several times so far in his quest to catch Spectre. The other is “Franz Oberhauser,” a name that means nothing to viewers at this point.

The audience doesn’t know it yet, but Waltz is Oberhauser. He’s also Ernst Stavro Blofeld, the notorious leader of Spectre (or SPECTRE, back when the name was still an acronym) from the classic Sean Connery Bonds of the 1960s. And therein lies one of the big problems with this sequence, and with Spectre as a whole: The deliberate withholding of information from the audience for the purposes of a manipulated twist — a twist that hardcore fans will see coming a mile away and casual fans won’t care about in the slightest.

From the moment they lock eyes in Italy, Bond knows who Oberhauser is, and Oberhauser knows who Bond is. But neither explains any of this to the audience for at least an hour of the movie. It’s not until the climax, when Bond arrives at Blofeld’s secret desert lair, that we learn their shared history; Oberhauser’s father raised James Bond after his parents died, infuriating Franz (he’s a poor sharer, in addition to being a mad supervillain). In retaliation, he killed his father and faked his own death in an avalanche. He calls Bond a cuckoo because of their practice of hiding their eggs in other birds’ nests.

This revelation would be cuckoo too — if every piece of marketing, and even the goddamn title of the movie didn’t telegraph it. If you know James Bond, then you know that Spectre means Blofeld; he’s the only guy who ever appeared in the old Connery movies as the leader of the group. If you don’t know James Bond, then it doesn’t matter what the guy’s name is, because the movie has spent its entire runtime building this artificial puzzle rather than providing a backstory that would give you a reason to care about Blofeld or Oberhauser or whatever you want to call him.

Rumors that Waltz would play Blofeld surfaced in November of last year, before the film’s official cast and title were announced. But even after that very public rumor, even after producers unveiled Spectre as the 24th Bond’s name, even after the trailers all hinted that Waltz was playing Blofeld, the entire cast and crew denied it. (In an interview with ScreenCrush last year, Waltz said he could “guarantee” his character’s name was Franz Oberhauser.)

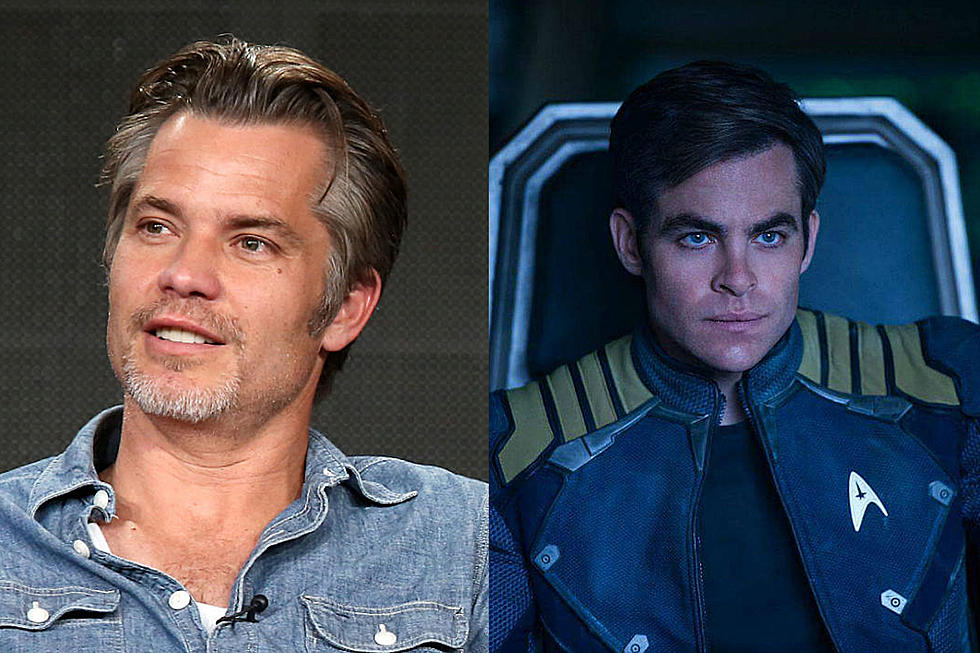

He was telling the truth — but it was a truth created purely to service a deception, hiding the character’s real identity for as long as possible so it could be revealed in a “huge” third-act “twist.” The whole structure of the trickery and the reveal is remarkably similar to the one surrounding 2013’s Star Trek Into Darkness, where director J.J. Abrams conspired to perpetrate a disinformation campaign around the identity of his film’s villain. In interview after interview, Abrams and the rest of his cast swore up and down that Cumberbatch was playing a man named John Harrison, and not Khan Noonien Singh, the famous baddie of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan originally portrayed by Ricardo Montalban. In his first scenes in the film, Cumberbatch was indeed referred to as Harrison, but after a while he reveals that’s a cover identity. “My real name,” Cumberbatch dramatically declares. “Is Khan!”

Notice how long it takes for the camera to cut to Chris Pine and for the scene to continue; a small beat presumably placed there to give the audience a chance to gasp and try to maintain control of their bowels while they grapple with this “shocking” announcement. Captain Kirk, on the other hand, doesn’t react in any way, because there’s no reason for him to; Pine’s Kirk never fought Cumberbatch’s Khan in the Mutara Nebula, the way Shatner’s Kirk did with Montalban’s Khan in Star Trek II. Pine’s Kirk’s never even heard of Khan. He might as well have said his name was Captain Hornswoggle Pussywillow.

The scene where Oberhauser finally says the name Ernst Stavro Blofeld proceeds in almost exactly the same way. Bond just stares back at him because there’s no reason he would care if Oberhauser changed his name to Blofeld, because Daniel Craig’s Bond has never met Blofeld. Both the Spectre and Into Darkness twists only make sense on a metatextual level. Within the narrative, they’re totally worthless. And yet they are the focal points of all the energy within these movies; energy that builds to revelations that have no meaning to any of the characters, and are only of interest to a small percentage of the audience that knows enough about the property to guess what’s being hinted at hours (if not weeks or months) ago.

This is not the right way to use a twist. Great movie twists are the ones you don’t see coming; like the stunning reveals at the end of The Usual Suspects, Planet of the Apes, or The Sixth Sense. Think of how hard Alfred Hitchcock worked to keep audiences from realizing that Norman Bates was (SPOILER ALERT FOR THE MOST FAMOUS HORROR MOVIE OF ALL TIME THAT IS NOW 55 YEARS OLD) dressing like his mother to kill his victims. Every aesthetic choice he made — rapid cuts during the famous shower scene; having the camera lead the detective up the Bates house’s staircase, so it doesn’t seem out of place when the mother is seen from a high angle — was to preserve that secret.

At the same time, these movies all go to great lengths to subtly provide meaning for those twists before they ever occur, so that when those big shocks hit, they actually mean something. People spend the entire movie talking about Keyser Soze before his real identity is divulged in The Usual Suspects. Norman tells Marion Crane about his complicated history with his mother. The Sixth Sense is about a kid who sees ghosts and then at the end you discover one of the characters was a ghost all along.

Spectre (and Star Trek Into Darkness) do the exact opposite. Every Bond fans sees the Blofeld twist coming, because Spectre is basically a reboot of all the old Bond movies where Blofeld led Spectre (just as Star Trek Into Darkness is basically a rejiggered update of Wrath of Khan). And in a desperate attempt to preserve what little surprise there might be, the movie makes no mention of Blofeld before Blofeld does (or of Khan before Khan does). It’s not as if MI6 is investigating Blofeld, searching the world for this notorious international terrorist. They don’t even know Oberhauser is alive. His alias is an insignificant detail. A nugget of trivia.

Movies like Star Trek Into Darkness and Spectre represent a strange and troubling confluence of incompatible pop cultural trends: Fandom’s increasing obsession with anticipating blockbusters with years of hype and theorizing, and Hollywood’s continuing obsession with endlessly remaking the same handful of stories over and over again. Each new tentpole release is met with thousands of words of conjecture and hundreds of screengrabs and GIFs; literally every single poster and publicity still and teaser and television ad and piece of ancillary merchandise is subjected to a level of scrutiny that would awe Talmudic scholars. We’ve arguably reached a point in film culture where movie marketing is more carefully analyzed than the movies themselves.

That could be because the movies themselves are so brazenly recycled from existing works, that they don’t actually demand much consideration. Spectre makes no secret of the source material it’s mining, and yet it persists for almost two hours in attempting to turn the organization’s leader into this grand enigma. The only person satisfied by this sort of unveiling is a fan who’s spent the last three years studying each Spectre trailer and plot synopsis, and correctly intuited that Waltz was playing Blofeld.

For the rest of us, the whole enterprise is at cross-purposes. Why make a mystery out of something obvious? Would you remake A Nightmare on Elm Street and announce the lead was playing a shadowy figure named Frederick Krugeman? Or a Batman movie where the hero is cast as “Bill Whine”? If the solution to the riddle you’ve based your entire movie around is “Exactly What You Thought It Was the Whole Time,” then maybe it’s time to propose an alternative.

Movie studios aren’t going to stop rebooting popular properties while those reboots keep making money. What needs to change in their place is how those stories are told. Movies are not NBC public service announcements; the more you know, the less you care. Rather than simply trading on their old cachet, how about investing these old ideas with a little new cachet? Filmmakers need to either embrace the iconic characters they’re rehashing, or find new ways to truly swerve audiences. These movies need to serve their story rather than the speculation of their hardcore fans, and reward paying customers, not just people who like to forecast what will happen in movies based on their advertising.

More From ScreenCrush