‘The Big Short’ Review: A Big Laugh at the End of the Financial World

It only takes Adam McKay three minutes to prove he was the perfect person to direct The Big Short.

On paper, it sounds like a weird fit. The guy who created goofy comedies like Anchorman and Talladega Nights making a movie about the 2008 financial collapse? But then you remember the closing credits of McKay’s The Other Guys, a series of animated infographics about the crisis and widespread Wall Street corruption. And anyone who follows McKay on Twitter knows he’s got passionate political views, particularly about unchecked corporate greed. Still, we’re talking about the man who made the movie where Will Ferrell teabagged a drum set. He directed a 130-minute movie about mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligations? Seriously?

Yes, seriously — or pretty funny, in this case — and in three minutes McKay shows why, when he finds the original sin of the housing bubble in the world of 1970s banking, where mortgage bonds were first created and the men and women of 2008 were doomed to some $5 trillion in losses to their pensions, retirement funds, and homes. It’s really no different than the people and values McKay mocked in Anchorman; the fraternity of the dumbest and most entitled white male douchebags on the planet. In a sense, The Big Short is the story of how those entitled douchebags teabagged the American people for years (metaphorically speaking), and McKay is very much in his element. The Big Short is the story of that teabagging, told from the perspective of the men who saw the balls coming; too late to stop them, but just in time to place a bet on how they would taste.

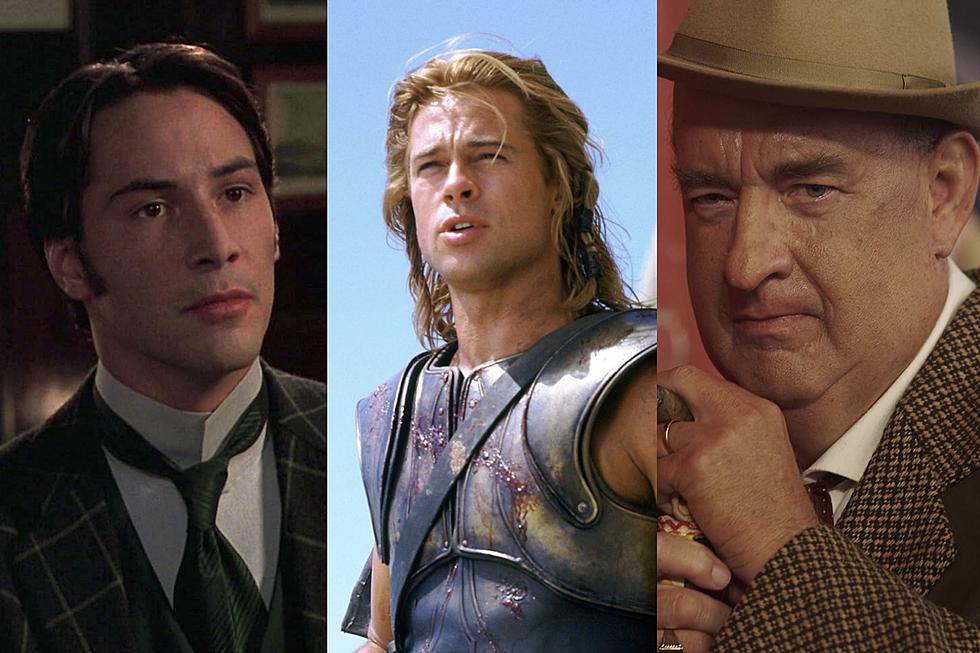

Based on the nonfiction book by Michael Lewis, it follows a loosely connected group of Wall Street traders and financial analysts — some of whom never meet or speak to one another — as they identify and wager against the central weakness in the global economy, namely these bad home loans (and their wildly inaccurate credit ratings) that were being handed out in the early 2000s like Kit Kats on Halloween. Dr. Michael Burry (Christian Bale), a socially awkward hedge fund manager with one eye, a bad haircut, and an unexplained hatred of shoes is the first to identify the opportunity. His purchases of more than $1 billion in credit default swaps catches the attention of Jared Vennett (Ryan Gosling), a arrogant trader at Deutsche Bank, whose fake tan and intense air of sleaze makes him look like he just came from an audition to star in the touring company of The Wolf of Wall Street. He brings his plan to short the bad mortgages to another hedge fund manager, Mark Baum (Steve Carell), who loves to stick it to shady financial institutions. And all their activity eventually attracts a couple young investors (John Magaro and Finn Wittrock) who correctly intuit which way the wind is blowing and convince an eccentric retired trader (Brad Pitt) to help them make the deal of the century.

That deal involves financial products so complicated that even the people buying and selling them often don’t understand how they really work. Somehow, the brilliant and funny screenplay by McKay and Charles Randolph manages to explain most of these arcane bonds and loans in a way that makes them (mostly) comprehensible to the average layman. Even more impressively, they do it in entertaining and funny fashion. Fast-talking Jared Vennett gives one speech on collateral debt obligations using a tower of Jenga blocks. And several celebrities make hilarious surprise cameos to break down other unintelligible concepts into ideas anyone can understand. If any of my high school economics classes were half as enjoyable as this movie, I might not have become a film critic.

As the crisis picks up steam, the movie begins accruing apocalyptic atmosphere; The Big Short is bleak and bitter and sometimes really scary, particularly to a journalist who’s about to bring his first child into the world and has no idea how he’s ever going to afford her college education. But McKay manages to keep the film funny too; it’s never quite as outrageous as something like Anchorman, but it’s less removed from that sort of machismo-deflating mockery than you might expect. He also brings his love of decimating genre conventions — in this case, the biopic. When the movie’s plot takes dramatic license that feels convenient, the characters break the fourth wall and acknowledge it, which lends the absurd moments that they later insist actually happened an extra level of oomph. If Dr. Strangelove had gotten out of the nuclear-war business and got a job in financial planning at Morgan Stanley, his misadventures might have looked like The Big Short’s combination of doomsday horror and ink-black comedy.

The standout in the cast is Gosling, who narrates much of the movie radiating the sort of charm that helped men like Vennett break the economic rules for years and decades. At the other end of the spectrum is Carell, following Foxcatcher and Freeheld with yet another woefully over-the-top and extremely unnatural biopic performance. The jokes finally fall away in the didactic ending, and The Big Short stumbles when it tries to humanize its characters (particularly Baum, who’s the only one who spends any time with his family, a wife played by a wasted Marisa Tomei). McKay’s strengths have never been melodrama or sentimentality; his best work comes when he spins observations into wild satire, and that’s the stuff that really connects in The Big Short.

Still, even if it falls a little short as a character study, the fact that it’s both hugely weird and hugely watchable is impressive. The whole foundation of this movie is as rickety as the crappy subprime mortgages that inspired its story. That the whole thing never collapses in the same way is to McKay’s credit. The guy has some real filmmaking cojones.

More From ScreenCrush