Arnold Schwarzenegger Is a Serious Auteur and It’s Time Everyone Acknowledged It

Arnold Schwarzenegger has you fooled.

He’s convinced you he’s nothing more than a catchphrase generator. A bodybuilder, not a brainiac. A nostalgia act trapped in the past.

But like the Terminator, whose fleshy exterior hides a heavily armored metal endoskeleton, there’s a lot more to Schwarzenegger than meets the eye.

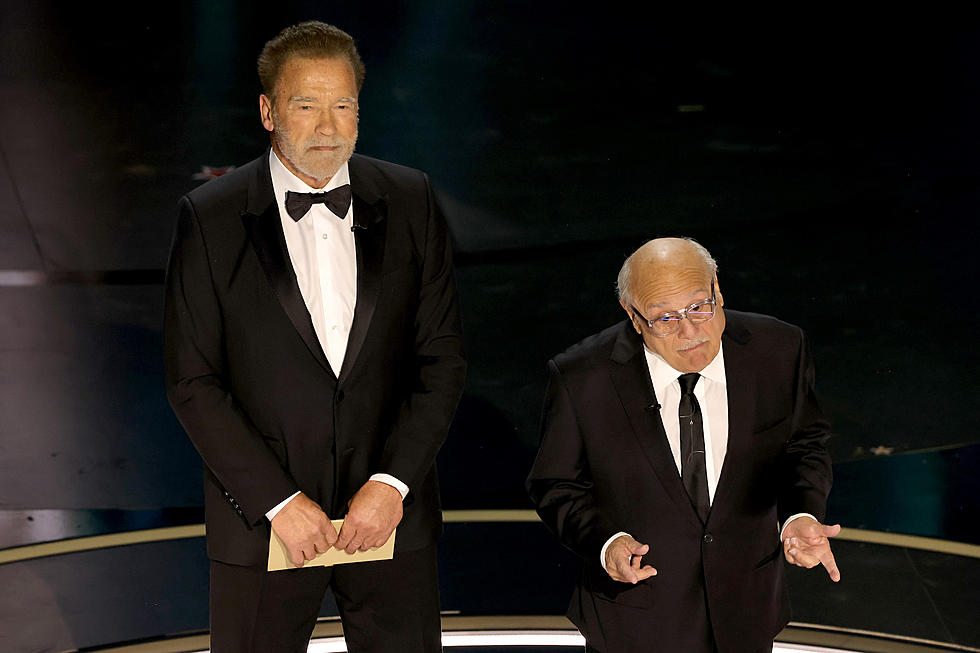

For 40 years, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s made a career out of defying naysayers and upending audience’s expectations. His first onscreen performance was so bad the film’s distributor redubbed his entire part — so he took acting and English lessons. Hollywood labeled him a meathead who was too big and bulky to play a leading man — so he fought for the leading role in Conan the Barbarian and turned it into a surprise hit. Critics pigeonholed him as a one-note bruiser — so he tried comedies and family films and became an even bigger star. (Adjusted for inflation, Twins would be the fourth highest grossing movie of 2015 so far.) Pundits laughed at his political ambitions — and a few years later he was the governor of California. Underestimate this man at your own peril.

It’s a mistake to underestimate him as a filmmaker as well. Schwarzenegger’s movies have grossed well over $1 billion worldwide and he influenced and inspired a generation of young moviegoers. Admittedly, it’s been a dozen years since he had a $100 million hit at the domestic box office (2003’s Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines), and he’s yet to produce anything with significant pop-cultural impact since returning to full-time acting in 2013. But a careful consideration of his entire career reveals a singular (albeit heavily accented) voice speaking loudly and clearly through all those films. Laugh all you want, but Arnold Schwarzenegger is an auteur.

He’s certainly not a conventional one though. The auteur theory has always focused on the study of directors as the sole authors of movies, and as the primary influence on a film’s quality and meaning. By that measure, Arnold Schwarzenegger is not an auteur. With the exception of an extremely random remake of 1945’s Christmas in Connecticut, he’s never directed a film.

But in Andrew Sarris’ “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962,” the great Village Voice critic argues that the “main criterion of value” when watching movies is “the distinguishable personality of the director.” Schwarzenegger may not be a director, but he’s got that distinguishable personality part down cold. And it’s worth noting that while directors are typically movies’ day-to-day decision makers, it’s often the star, whose name alone is enough to secure a green light and budgets of hundreds of millions of dollars, who holds the most clout. The director might have the final say on set. But sometimes the star has the final say over whether that director gets or keeps their job.

For that reason, I’ve long felt we need to expand the auteur theory to consider powerful actors — or perhaps to create a new term to describe an actor who is powerful enough to be considered a crucial author of his work. I like the word “acteur,” which combines actor and auteur. Recently, the Museum of Modern Art started an occasional repertory program dedicated to “acteurism,” which highlights the work of “actors who were able to develop their screen personalities with sufficient consistency and vivacity that they themselves became vehicles of meaning in their movies.”

At age 67, Schwarzenegger’s best days as an action hero are unquestionably behind him. But as an acteur, he’s still in his prime.

Schwarzenegger would be an ideal candidate for his own MoMA acteurism series. He’s had a consistent and vivacious screen personality for four decades — and for most of his post-Terminator career he had the ability to choose what writers and directors he worked with, what projects they made, and what roles he played. Every choice reflected his feelings as an artist, and the result of those choices is a filmography packed with themes that reoccur and evolve from year to year, and from movie to movie.

I could go one film at a time, outlining how every single one — from his disastrous debut, Hercules in New York, to this week’s Terminator Genisys — expresses some part of Schwarzenegger’s personality or philosophy. But rather than subject you to the longest article in human history about Arnold Schwarzenegger, let’s make things a bit more manageable and group things by theme. These are some (but by no means all) of the ideas expressed by the films of actor (and acteur) Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The Immigrant Experience

“I’m tired of the same old faces, the same old things!” — Hercules in New York (1969)

One moment made Arnold Schwarzenegger into Arnold Schwarzenegger.

In his autobiography, Total Recall: My Unbelievably True Life Story, Schwarzenegger describes a single act at age 14 made him want to be a bodybuilder. “I’d just seen the movie Hercules and the Captive Women, which I’d loved.” Schwarzenegger writes. “I realized I wanted to be strong and muscular.” He became a huge fan of the film’s star, Reg Park, who was a champion bodybuilder and Mr. Universe, and who inspired the teenage Schwarzenegger to begin lifting weights.

Before his bodybuilding skills brought him to America, Schwarzenegger lived in a small Austrian village named Thal with his brother, mother, and his stern policeman father, Gustav. Here’s how he describes Gustav’s approach to parenting:

His answer to life was discipline. We had a strict routine that nothing could change ... When we were a little older and starting to play sports, exercises were added to the chores, and we had to earn our breakfast by doing sit-ups. In the afternoon, we’d finish our homework and chores, and my father would make us practice soccer no matter how bad the weather was. If we messed up on a play, we knew we’d get yelled at.

After Schwarzenegger’s bodybuilding career took off, he jumped at the chance to make his film debut in a Hercules movie. And even though Schwarzenegger insists today that he “couldn’t even understand all the sentences in the script,” and even though the movie was truly awful, Hercules in New York still perfectly expressed his journey to that point, showing a brash, young man of incredible power who grows weary of living under the thumb of a disciplinarian father and dreams of escaping to America.

There may not be a worse line reading in cinema history than Schwarzenegger saying “I’m ti-yuhd of zee zame old fay-says. Duh zame old tings!” But even if he couldn’t say the words yet, Arnold understood the sentiment. Even as Schwarzenegger settled in America and became a U.S. citizen, he continued to relate to the immigrant experience, and to choose roles that cast him as an outsider navigating an unfamiliar world.

Sometimes those immigrants were fairly traditional, and close to Schwarzenegger’s own life experiences, like Julius Benedict from Twins, who comes to America searching for his brother and finds himself unprepared for (yet excited by) the hustle and bustle of Los Angeles. Others were more unconventional. We might not consider the Terminator an “immigrant” in the customary sense, but what else is it if not a stranger in a strange land? It’s come from a distant future to an alien landscape, where it finds itself deeply out of touch with the local customs and conventions.

The character’s expat qualities were really played up in Terminator 2: Judgment Day, where the evil robot, now reprogrammed to protect John Connor instead of kill him, slowly discovers what it means to be human. The Terminator’s process of learning customs, adopting slang (“Hasta la vista, baby.”), and making a new family in his new home put a sci-fi spin on a process Schwarzenegger himself knew well from his own journey to assimilate.

Schwarzenegger returned to the idea of a foreigner in new or exotic surroundings again and again. In Predator, he’s an American soldier in the jungles of Central America (fighting another powerful immigrant, this one from another planet). In Collateral Damage he’s a firefighter from Los Angeles who follows a terrorist to Colombia. In Red Heat, he’s a Russian police officer who follows a drug kingpin to Chicago. In Total Recall, he travels to Mars, where he gets mixed up in a surreal battle between colonists and mutants. In Last Action Hero, he leaves the fictional world of movies for “real life,” which operates by a completely different set of rules than the universe he knows. And in Kindergarten Cop he ventures into the most unfamiliar territory of all: A classroom full of unruly children.

These movies run the gamut from comedy to sci-fi to horror to action, and almost all of them come from different directors and writers. The constant is Schwarzenegger, and their mutual exploration of the joys and anxieties of immigration.

The Man Who Sees Doubles

“If I’m not me, then who the hell am I?” — Total Recall (1990)

That’s Douglas Quaid (Schwarzenegger), talking to his wife Lori (Sharon Stone). Quaid believes he’s a humble (if exceptionally muscular) construction worker, but when his wife tries to kill him he realizes he’s actually a spy named Howser. The rest of Total Recall follows Schwarzenegger as he learns about his past and tries to determine his true identity, Quaid or Howser.

Schwarzenegger’s search for his one, true identity forms the foundation of many of his movies — at least half of his filmography, by my count. He often plays one man with two personas, like Quaid and Howser in Total Recall, or two men sharing one persona, like Adam Gibson and his clone in The 6th Day, or two identical men who share an uncanny physical resemblance (like Jack Slater and “Arnold Schwarzenegger” in Last Action Hero). This fascination with doubles and doppelgangers remains a constant throughout Schwarzenegger’s work, one I explore further in this video essay, “Arnold Schwarzenegger: Double Vision.” Enjoy.

The Family Man

“Watching John with the machine, it was suddenly so clear. The Terminator, would never stop. It would never leave him, and it would never hurt him, never shout at him, or get drunk and hit him, or say it was too busy to spend time with him. It would always be there. And it would die, to protect him. Of all the would-be fathers who came and went over the years, this thing, this machine, was the only one who measured up. In an insane world, it was the sanest choice.” — Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991)

Arnold Schwarzenegger became a movie star playing a literal killing machine.

He was the Terminator; a remorseless computerized assassin. In the wake of The Terminator’s success, he reeled off a string of a movies where he starred as similarly unstoppable killers; Commando, Predator, The Running Man. In his book The Blood Poets, author and scholar Jake Horsley once called these movies “genocide-flicks,” and claimed that “the idea of a Schwarzenegger character having an ordinary life, even one as stark and empty as that of Dirty Harry... is unthinkable to the Schwarzenegger mythos.”

For a time, Horsley was absolutely correct. But in the early 1990s, Schwarzenegger made a significant course correction in his role choices; away from killing machines and toward more humane, family-oriented action heroes. Suddenly all of his characters had ordinary lives, or they were broken men who desperately wanted ordinary lives, like Det. John Kimble from Kindergarten Cop, whose tough-as-nails Dirty Harry-style attitude actually masks the pain of losing his wife and son, and who finds new purpose as a kindergarten teacher (and reconstitutes a new family with one of his students and a co-worker). Even the Terminator became a dad; as the voiceover above from Terminator 2 suggests, he embraced the role of surrogate father to John Connor, and ultimately sacrificed his own robotic life to save him.

So what changed around 1990? The real Schwarzenegger, like the onscreen one, became a family man. Schwarzenegger married Maria Shriver in 1986, and his first daughter, Katherine, was born in 1989, right as he was preparing to make Kindergarten Cop.

In interviews around that time, Schwarzenegger talked about how married life had begun to shape his choice of roles. He told film critic (and future director) Rod Lurie that Shriver had become “instrumental” in everything he did. “Maria has very good instincts,” Schwarzenegger told Time’s Richard Corliss. “She reads fast, she analyzes and — boom! — she has the notes. Like an agent.”

Under Shriver’s influence, Schwarzenegger played fewer and fewer loners and psychos, and gravitated towards movies with more central parts for women. Terminator 2’s Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) is as much of an action hero as the Terminator himself. In True Lies, Schwarzenegger’s Harry Tasker saves the world with the help of his wife Helen (Jamie Lee Curtis), after he finally reveals the secret of his double life as a spy and then makes her his partner. Stories about families would become Schwarzenegger’s preferred subject matter — until secrets from his own family life resulted in another seismic shift in his filmography.

The Fallen Hero

“You think you're bad, huh? You're a f---ing choir boy compared to me! A CHOIR BOY!” — End of Days (1999)

Maybe Arnold Schwarzenegger was good at playing a robot because he is a robot.

That is the impression one gets reading his autobiography, particularly the chapter about his affair with his housekeeper and their son, Joseph. The chapter is called “The Secret” and it is Schwarzenegger’s account of a marriage counseling session where Maria Shriver finally confronted him about Joseph’s paternity. Joseph was born in 1997, and Schwarzenegger learned the truth some time after that, but never discussed it with his wife until he’d left the office of Governor in 2011. Pressed to explain why he’d kept the truth buried for so long. Schwarzenegger said he was embarrassed, and didn’t want to hurt Shriver’s feelings, Moreover, though, he claims:

“...Secrecy is just part of me. I keep things to myself no matter what. I’m not a person who was brought up to talk ... Much as I love and seek company, part of me feels that I am going to ride out life’s big waves by myself.”

For more than a decade, Schwarzenegger rode one of his life’s biggest waves alone. When the truth came to light, he gave a tell-all interview to 60 Minutes’ Lesley Stahl. In it, he described how he succeeded at bodybuilding by compartmentalizing his emotions and focusing completely on the task at hand.

"The thing that can really make you lose is if you get emotionally unbalanced. If I put everything that's happening emotionally on deep freeze — so I became an expert in living in denial."

Ironically, after all those years of living in denial, Schwarzenegger was preparing to wrestle with this hidden chapter onscreen in a project called Cry Macho (about “a horse-trainer’s friendship with a streetwise twelve-year-old Latino kid”) when the scandal broke and the film’s producers canceled the project. But while Schwarzenegger didn’t publicly acknowledge this personal failure until recently, his movies in the years after Joseph’s birth hint at it with one storyline after another about fathers and husbands who’ve failed their children and spouses, and who inevitably lose their families after making terrible mistakes. In hindsight, they feel like expressions of guilt and remorse, apologies from a man who hasn’t even confessed to doing anything wrong yet.

Take, for example, End of Days, where Schwarzenegger plays Jericho Cane, an alcoholic, depressed New York City cop still mourning the murders of his wife and daughter. Or Collateral Damage, where Schwarzenegger’s Gordy Brewer fails to protect his wife and son, who are killed in a terrorist bombing attack. In The 6th Day, family man and helicopter pilot Adam Gibson finds himself replaced by his own clone; at the end of the movie, the Adam we’ve followed through most of the movie must leave his family behind for a life alone elsewhere.

Just a few years earlier, Schwarzenegger played the guy who always triumphed over impossible odds while fixing broken or troubled families. He found his brother and started a new life with him in Twins. He reconnected with his unhappy wife and rescued his daughter in True Lies. He proved his worth as a dad in Jingle All the Way. After 1997, none of his characters are happily married. All of them have failed as fathers and husbands. They’ve lost. They’ve screwed up. They seek redemption, and rarely find it.

Schwarzenegger’s search for redemption has continued since he returned to Hollywood after his terms as Governor of California (and after the existence of Joseph became public knowledge). In The Last Stand, he plays a disgraced LAPD cop whose partner was crippled in a botched drug raid. In Escape Plan, Schwarzenegger’s Emil Rottmayer has been locked away in a maximum security prison and he agrees to help another inmate played by Sylvester Stallone escape so that he can reunite with his daughter. He plays another widower in Sabotage, where his DEA agent, John Wharton, remains traumatized following the murders of his wife and child by Mexican drug cartels.

Very few of these movies have been blockbusters; many have been outright flops. But Schwarzenegger’s persisted in mining this strain of grief and anguish right up until today. In this year’s domestic horror drama Maggie, Schwarzenegger must work up the courage to kill his daughter after she contracts a zombie virus. “I promised your mother that I would protect you,” he tells Maggie (Abigail Breslin). But he didn’t. Maggie gets infected.

As Maggie slowly turns into a member of the undead, it falls to Schwarzenegger’s Wade Vogel to murder her before she hurts anyone else. That’s quite a shift from the Terminator, the main who could kill dozens of people without an ounce of remorse. Or at least that was quite a shift from the old Terminator; in Terminator Genisys, there’s a moment where Schwarzenegger’s T-800 must decide whether or not to kill Sarah Connor for the good of humanity. Even robots wrestle with guilt sometimes.

The Aging Titan

“I'm an obsolete design.” — Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines (2003)

Besides his version of Christmas in Connecticut, the “Director” section of Schwarzenegger’s IMDb page includes just one other credit: A 1990 episode of Tales From the Crypt called “The Switch.” It’s about a wealthy old man named Carlton (William Hickey) who falls madly in love with Linda (Kelly Preston), a much younger woman. He asks her to marry him, but she’s not attracted to his decrepit features. His quest to win Linda’s heart leads him to a mad scientist who offers to give him the face of a much younger man named Hans (Rick Rossovich). A series of surgeries give Carlton the looks and the physique of a man many decades his junior, but at the cost of his fortune. Fully transformed, Carlton (looking like Hans) finally returns to Linda, only to find, in a typical Tales From the Crypt twist, that she’s already gotten married — to Hans (looking like Carlton) who now has all of Carlton’s money. [Cue Cryptkeeper laugh.]

Apart from a self-referential cameo in the introduction, “The Switch” bore little resemblance to Schwarzenegger’s movie output at that time. It’s not an action movie, and it doesn’t feature any punning one-liners. It’s only in retrospect, after Schwarzenegger got older and his famous physique started to age with him, that the episode’s obsession with youth and physical vitality began to take on more autobiographical significance.

That significance also dates to 1997, which was a surprisingly eventful year in Schwarzenegger’s life. A few months before he fathered two sons with two different women, Schwarzenegger had surgery to correct a hereditary defect in his heart. The initial surgery didn’t go well; Schwarzenegger ultimately had to go under the knife a second time to fully repair a faulty valve. In Total Recall, Schwarzenegger reveals the paralyzing fear he felt as the anesthesia began to take effect, when “you’re losing consciousness and don’t know if you’ll ever wake up.” Schwarzenegger did wake up and before too long he was back up on his feet; back in the gym and back at work in Hollywood. But that brush with death seemed to permanently color his characters from that point forward.

Before the surgery, Schwarzenegger’s characters were ranged from unstoppable robots to humans who with the strength and stamina of unstoppable robots. In Commando, his character storms the island fortress of a former South American dictator, kills approximately 80 soldiers, rescues his daughter, and walks away with a couple minor scratches. In The Running Man, he’s sent into a suicide gauntlet of high-tech gladiators; he slaughters them all and then brings down the corrupt gameshow that mollifies the masses in his dystopian future. “If it bleeds, we can kill it,” Schwarzenegger famously said of the Predator alien (another seemingly insurmountable force he defeated with relative ease). By Schwarzenegger’s own logic, since he almost never bled onscreen, the Governator seemed unkillable.

Open-heart surgery changed all that. He died in his very first movie after the surgery; in End of Days, Jericho Cane sacrifices himself to defeat Satan and protect humanity from the Biblical apocalypse. A few years later, in his (temporary) farewell to Hollywood, Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines, he addressed his newfound mortality in a conversation with John Connor (Nick Stahl). When asked whether he’ll be able to defeat the latest, upgraded Terminator, Schwarzenegger replies, “Unlikely. I’m an obsolete design.”

When Schwarzenegger returned to Hollywood a decade later with The Last Stand, he picked up right where he left off, at least thematically speaking. Even the title suggested an awareness that the end is near.

The older Schwarzenegger gets, the more reflective he becomes. For that reason, Terminator Genisys is an interesting summation of his entire career to date. He plays yet another time-displaced immigrant, and in an early scene he faces off against another double, a younger model of the Terminator fresh off the assembly line. On IMDb, Schwarzenegger’s character is referred to as “Guardian,” but Emilia Clarke’s Sarah Connor Terminator calls him “Pops,” and in the film we see him fight to not only protect the future, but hold together his adopted family. Like the real Schwarzenegger, Pops has secrets he refuses to share; he can’t or won’t tell Sarah Connor who sent him back to the past, or why they did it.

Genisys repeatedly focuses on how much older Pops is than the guy in the first two Terminators. His hair’s gone gray. His hands shake and malfunction when he tries to reload guns with his trademark mechanical efficiency. At one point his knee gives out and he smacks it back into place, as if he’s struggling with a flare-up of robo-arthritis. Pops is hopelessly outmatched against Skynet’s newest Terminator, which can reconstitute itself using nanotechnology, and is as fluid as Schwarzenegger is stiff.

But as Pops insists over and over, he’s “old, not obsolete.” That’s a significant revision from Terminator 3, which was predicated on the notion that Schwarzenegger’s model was obsolete, and despite Genisys’ acknowledgement of the character’s inexorable physical breakdown, the film is actually the star’s most upbeat in 15 years.

Some might call this renewed positive attitude another form of denial; Schwarzenegger’s certainly been an expert at that at times in his life. I prefer to see this shift as the latest evolution of one of the most fascinating and underrated filmmakers of the last 30 years. At age 67, Schwarzenegger’s best days as an action hero are unquestionably behind him. But as an acteur, he’s still in his prime, producing some of the richest and most resonant work of his entire career.

More From ScreenCrush