‘Leaving Neverland’ Is a Haunting Account of Michael Jackson’s Alleged Abuses

Most interview subjects in documentaries are photographed at an angle, looking off to one side of the camera at the director who’s asking them questions. Almost everyone interviewed in Leaving Neverland is seated perpendicular to the camera. They might look off to the side of the lens, but they’re placed in the frame so that they’re seated facing right at us. It makes the delivery of their comments that much more direct and personal, as if they are speaking to us one on one, rather than with the mediation of a film crew. It makes it harder to evade their eyes and their message — even though a lot of people have not wanted to hear that message for a very long time.

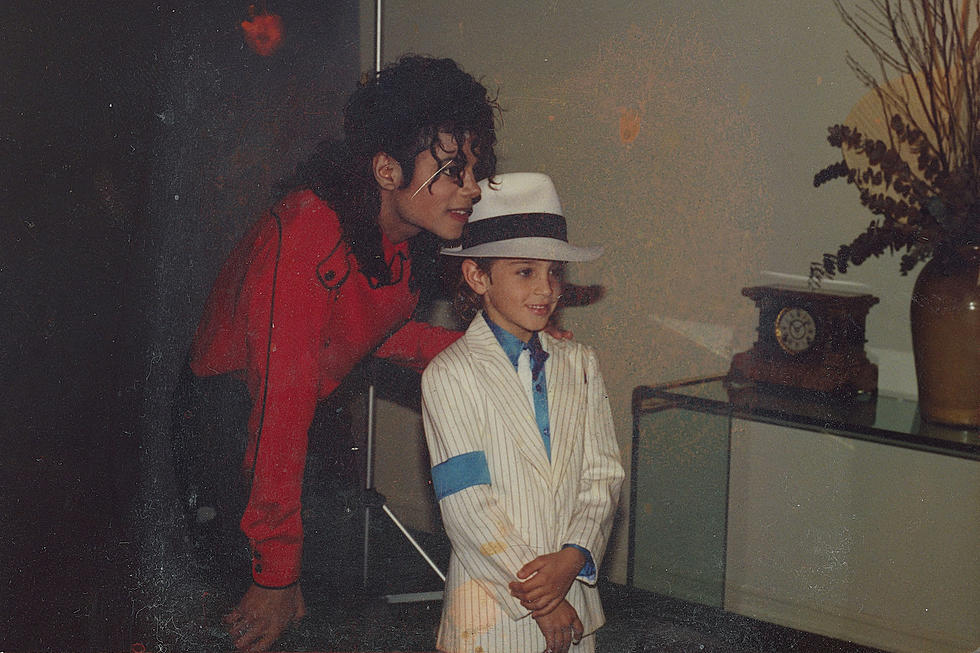

That’s because Leaving Neverland is essentially the accounts of two men, Wade Robson and James Safechuck, who claim that they were sexually abused as young boys by Michael Jackson. This documentary, directed by Dan Reed, is by no means the first time such allegations have been leveled against Jackson. Indeed, several previous cases are addressed in Leaving Neverland. In some of those cases Robson and Safechuck testified — on Michael Jackson’s behalf, in the days before they revealed the abuse they now say they endured for years.

Some will claim that Robson and Safechuck’s prior efforts to defend Jackson prove they are lying now. Others will look to the fact that both have sued the Jackson estate after the King of Pop’s death as further “evidence” of some malicious plot. (For more details on those suits, including some facts which are not discussed in Leaving Neverland, read this Slate article.) I am confident that this post, and any social media attached to it, will receive a fair number of comments and attacks from Jackson partisans who have not seen Leaving Neverland or read this article, simply because they want to discredit the film and its allegations, and discourage people from watching it.

To some extent, that is what Leaving Neverland and its methodical but confrontational approach is all about. Over the course of two two-hour installments, Robson, Safechuck, and their respective families lay out in painstaking (and sometimes simply painful) detail their experiences with Jackson. Jackson himself, who died in 2009, is seen in photographs, archival news reports, concert footage, and some of his more public defenses, like the famous one broadcast from his Neverland Ranch home in 1993. The 1993 case was eventually settled out of court; a 2005 trial about allegations of molestation of a 13-year-old boy ended with Jackson found not guilty. Those that wanted to believe Jackson — and to believe in Jackson, the artist — could use those examples to support their argument. Many have done exactly that, ignoring the various accusers to focus on his music, which became the soundtrack for so many people’s lives in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s — including my own.

With a musician as undeniably talented as Jackson, it’s only natural to want to hang on to those memories of his songs, his dancing, and his videos. Over four sometimes excruciating hours, Leaving Neverland forces viewers to come to grips with Robson and Safechuck’s memories of Jackson, which are of a far more horrifying sort. Both entered the pop star’s orbit at very young ages — Safechuck at 11, Robson when he was just 7 — when they were aspiring actors and dancers, respectively. They were looking for guidance, assistance, and approval. Whether Jackson ever laid a hand on either of them, they were, in the parlance of con men, “easy marks” for a person of power.

Regardless of whether you believe Safechuck and Robson or not, Leaving Neverland serves as a highly effective warning to parents of gifted children who might want to get into show business. The other main interview subjects in Leaving Neverland are the two accusers’ mothers, who both describe how they were attracted to, and in some ways seduced by, Jackson’s luxurious lifestyle. Even if Jackson never acted inappropriately, their parenting was absolutely negligent, and included removing their child from school so they could follow Jackson on tour around the world, often without parental supervision. The way ambition and the hunger for celebrity — or even the proximity to celebrity — rips these families apart, is heartbreaking in and of itself.

Reed intersperses his interviews with long drone shots of Los Angeles and Australia (Robson’s home). They evoke a feeling of flight that’s no doubt designed to echo, in an ironic way, the title of the film. There is no escape from the past for Robson and Safechuck. Though Jackson partisans will insist Leaving Neverland should have included more interviews from “the other side,” perhaps with surviving members of the Jackson family or investigators, the film’s blunt, unambiguous approach means that for four hours, we cannot escape these stories either. And after the film is over, those stories are very hard to shake.

Gallery — The Best Films of 2018:

More From ScreenCrush