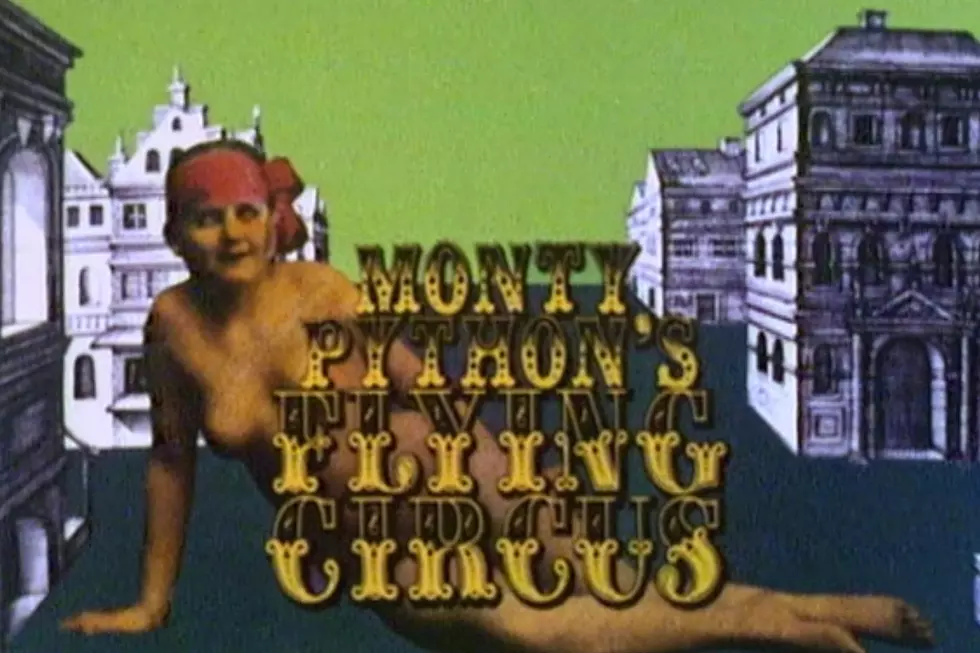

50 Years Ago This Week, ‘Monty Python’s Flying Circus’ Changed Comedy Forever

On Oct. 5, 1969, Monty Python’s Flying Circus debuted on the BBC. The immediate response was harsh. One network executive called the program “disgusting,” while another opined that the comedy troupe went “over the edge of what was acceptable.” Outraged with the show’s first episode, and disappointed in its low ratings, the network contemplated an immediate cancellation. Instead, Monty Python’s Flying Circus survived, going on to become one of the most influential comedies in television history.

The show’s creation can be traced back to a rather unlikely source. David Frost, who would later make a name for himself as a groundbreaking journalist, originally had dreams of becoming a comedian. He was a member of Footlights, a theatrical society at Cambridge University known for fostering emerging young talent. Frost was cast as the host for That Was The Week That Was, a news satire program airing on the BBC. Among the show’s writers were two of Frost’s fellow Footlights alumnus, John Cleese and Graham Chapman.

That Was The Week That Was would last two seasons. The trio would again collaborate on the At Last the 1948 Show, a sketch series that featured Cleese and Chapman among the cast, while Frost served as producer. Though the program was short-lived, its structure served as the foundation for Flying Circus. The famous catchphrase “And now for something completely different” would originate on At Last the 1948 Show, while several of the show’s sketches would later be reworked for the Monty Python series.

Comedy writers in London at the time would frequently work on multiple series, leading Cleese and Chapman to cross paths with other future Monty Python members. In a 2015 appearance on The Late Show, Cleese remembered watching the children’s show Do Not Adjust Your Set, which Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones and Michael Palin were writing. “It was the funniest thing on English television,” the comedy legend recalled. “We rang them up one day, because we knew them, we had worked together before, and said ‘Why don’t we do a show together?’ And they said, ‘Yeah, why not.’”

The newly formed troupe secured a meeting with BBC head Michael Mills and quickly assembled for a pitch. Only problem, they hadn’t determined what the show would be. “We hadn’t discussed it,” Cleese confessed, later describing the meeting as “professional suicide.” “It wasn’t a pitch. I was a non-pitch. It was an un-pitch. It was an ex-pitch,” the comedian admitted. Still, on a gut feeling, Mills gave the production a green light.

With a deal in place, the comedy group and its series both needed names. Monikers like "Owl Stretching Time" and "The Toad Elevating Movement" were thrown around. The BBC liked the phrase “Flying Circus” and printed the title on their schedules before the troupe officially gave it their approval. The comedians knew they wanted a name to go before the title and toyed with “Arthur Megapode’s Flying Circus” and “Gwen Dibley’s Flying Circus.” Eventually, they settled on the moniker Monty Python; the first name a tribute to British World War II general Field Marshal Lord Montgomery, and the last name being “a slippery-sounding surname”.

The BBC hated the name, but their displeasure over the title paled in comparison to their response to the premiere of Monty Python’s Flying Circus. The debut episode featured sketches poking fun at World War II, lambasting the British social structure and depicting violence as a source of humor. Network executives were appalled, calling the acerbic comedy “nihilistic and cruel.” One BBC figurehead declared that Monty Python “wallowed in the sadism of their humor.”

The ratings for the first episode were extremely low, with only 3% of the U.K.’s audience tuning in. But while the show’s absurdity angered officials at the BBC, it also allowed Flying Circus to stand out. Traditional comedic devices were thrown out the window. Punchlines were negated, with sketches suddenly ending unresolved as the show moved on to a different scene. Seemingly unrelated characters would appear out of nowhere, such as Chapman’s Colonel who regularly appeared unannounced when things got “far too silly.” Crossdressing, fits of rage, historical events, silly walks - nothing was too strange, so long as it was funny. The show was, to steal its own phrase, “completely different’ than anything on television. By the end of its first season, Monty Python’s Flying Circus had become a counter-culture phenomenon.

Asked decades later about his group’s unique brand of comedy, Idle pointed to a certain mentality that came with growing up in World War II era London. “We were all war babies. We grew up with gas masks and rationing and bombed-out houses,” the comedian noted. “The London that had been blitzed was still very present, and we mocked all that.”

The series would last 45 episodes, spanning 1969 to 1974. Cleese would leave the group before its fourth and final season, sighting a desire to pursue other creative ventures. “I felt that Python had taken my life over and I wanted to be able to do other things,” the comedy icon declared many years later. “I wanted to be part of the group, I didn’t want to be married to them – because that’s what it felt like.”

The American audience didn’t get their first taste of Flying Circus until September, 1974, when Dallas PBS affiliate KERA became the first station in the U.S.A. to air an episode. While fans in the U.S. were still discovering the show, Monty Python’s Flying Circus was coming to a close across the pond. The final episode aired on the BBC Dec. 5, 1974.

Gallery — The Best Rock Movie From Every Year: 1955-2018

More From ScreenCrush