The Strange and Encapsulating Innocence of a Bad Movie: ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’

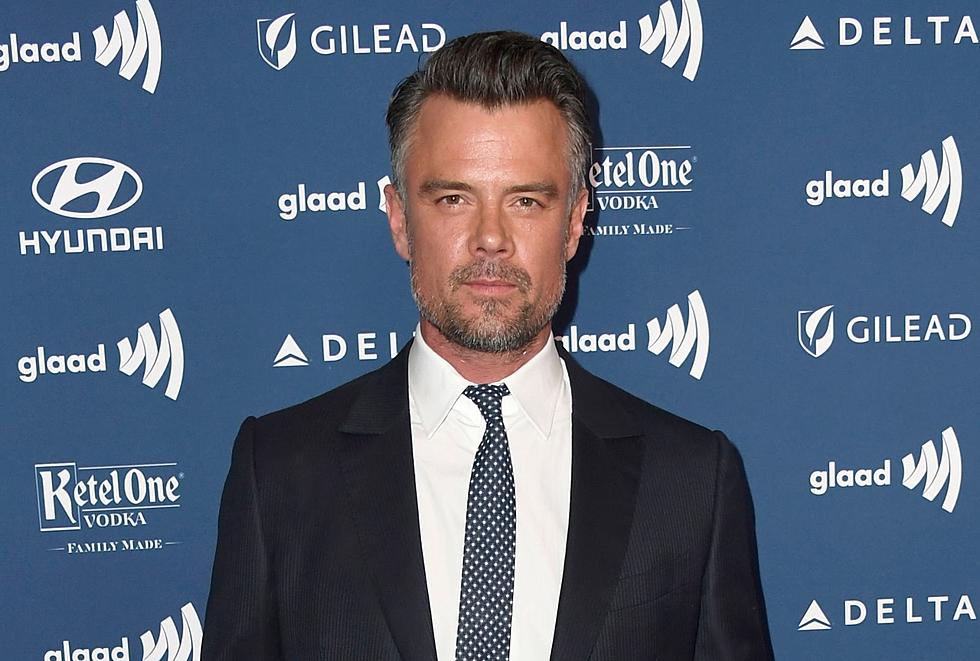

Over the past month, we’ve been deluged with advertisements for the home satellite service, DirecTV, featuring Rob Lowe playing himself alongside an extreme, less appealing version of himself. The most popular of these -- at least, the one that seems to air the most -- is “super creepy Rob Lowe.” (There are other variants like “painfully awkward Rob Lowe” and “hairy Rob Lowe.”) These commercials vary between terrible and awful. (And I do wonder if this is just another step in Rob Lowe’s master plan to rid the Internet of past indiscretions.) But, other than being awful, all of these commercials have something in common in that they all end with a snippet of ‘Love Theme from St. Elmo’s Fire’ by David Foster. It’s during these snippets that I stared to ask myself, “Did I ever actually see ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’?”

When Joel Schumacher’s ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ was released in 1985, I had just turned 11 years old. It’s a weird thing because ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ seems like such a quintessential movie of the ‘80s, yet I was kind of at that age when I certainly remember it existing – and will forever have John Parr’s ‘Man in Motion’ playing on an internal brain loop – and experienced its dominance of culture in the summer of 1985, though no responsible parent is going to take an 11-year-old kid to see ‘St. Elmo’s Fire' (including my own). And to be fair, I can’t imagine that the me who had just finished fifth grade would be too interested in a movie about coke-snorting college graduates. So for me, it kind of always existed in this vacuum of what I thought it was -- accelerated by its own hype at the time – rather than remembering anything about the actual movie. I had caught parts of it on premium cable, but, after watching it on Netflix over the weekend … I realized that, no, I had never watched ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ in its entirety.

It’s more a testament about celebrity and fame than it is anything the narrative of the movie is pretending to tell us.

It’s not surprising to learn that ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ isn’t a very good movie. But as an artifact of the time, it’s inherently fascinating as one of only two Brat Pack movies. (Most definitions of a “Brat Pack movie” – these definitions exist -- only include ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ and ‘The Breakfast Club’; everything else, like ‘Pretty in Pink’ or ‘Sixteen Candles’ are considered secondary Brat Pack movies.) (Also: I spent way too much time researching this.) There’s really not a lot going on in ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ other than everyone involved, with the exception of Mare Winningham and Andie MacDowell, having that, “Hey, look at me, I’m famous and I’m in a movie!,” look on their faces.

‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ follows seven college friends – played by Rob Lowe, Demi Moore, Andrew McCarthy, Emilio Estevez, Judd Nelson, Ally Sheedy, and Mare Winningham -- shortly after graduation from Georgetown. What’s immediately striking about this is just how grown up everyone is acting. Rob Lowe plays Billy and he’s the only one who acts like someone who just graduated from college, yet the others show scorn towards him because they are all adults now. The other peculiar character is Emilio Estevez’ Kirby Keager, who switches professions three times over the course of a 110-minute movie in an effort to stalk Andie MacDowell’s character. What maybe came across as “cute” in 1985, now comes across as downright disturbing. Kirby Keager should be behind bars.

Again, ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ fire is not a good movie and the point of the whole thing seems to be “from now on maybe we should go to brunch instead of the college bar.” (Though, ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ does have a “suicide by leaving your bedroom window open while it’s cold outside” attempt, which should win some sort of award for “most unique, yet laziest suicide attempt in film history.”) But there really is something fun about watching these actors sport around their “people love us, this will obviously last forever” attitudes.

People did not love them. On its opening weekend, ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ grossed just over $6 million and opened in fourth place, behind Clint Eastwood’s ‘Pale Rider,’ the second week of ‘Cocoon,’ and the sixth week of ‘Rambo: First Blood Part 2.’ (I truly believe ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ was almost more popular to those of us who didn’t see it, driven mostly by the amount of airplay the songs from its soundtrack received that summer.)

Adding to the general discontent toward ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ was a New York magazine piece that published shortly before the film arrived in theaters titled ‘Hollywood’s Brat Pack,’ which, yes, is the piece that coined that phrase. If you’ve got some extra time and have never read this David Blum what-can-only-be-called-a hit piece, please do. You will not regret it. Blum himself has backed away from it in recent years, but it’s basically every publicist's worst nightmare. Is the piece unfair? Kind of. Did pretty much everything predicted in this piece come true? Yeah, pretty much.

Basically, Blum hangs out with Emilio Estevez, Rob Lowe, Judd Nelson (and, strangely, Jay McInerney; it’s mentioned that Tom Cruise – also listed as “Emilio Esteves’ best friend" -- will play the lead in the adaptation of his book, ‘Bright Lights, Big City’, which obviously didn’t happen) one night during the peak of their powers. Along the way, they run into other famous people like Timothy Hutton, which leads to this passage:

The Brat Pack whispers that Hutton has made a near-fatal mistake; he has made movies that have failed at box office. For one of the pack, this is a mortal sin—because what makes you a member, what makes you a Brat, is the ability to be in a position where Hollywood needs you more than you need Hollywood. ‘Tim’s last three movies were bombs,’ one of the Brats noted, in a not-for-attribution remark.

Later, the subject of their ‘St. Elmo’s Fire’ co-star Andrew McCarthy is brought up. McCarthy, almost unfairly, gets thrown in with the rest of the “Brat Pack,” even though he’s certainly not friends with any of the rest of them. Pretty much proven by this exchange, “For actors so imbued with the ensemble spirit, the Brat Pack members are out for themselves. ‘Sean [Penn] is crazy with all of his role preparations, becoming the character in every way,’ one says. And of Andrew McCarthy, one of the New York-based actors in St. Elmo’s Fire, a co-star says, ‘He plays all his roles with too much of the same intensity. I don’t think he’ll make it.’ The Brat Packers save their praise for themselves.”

Oh, and then there’s Blum’s own fairly nasty assessment of Judd Nelson’s talents, “He made his reputation as a hood in 'Making the Grade' and 'The Breakfast Club.' And now, in 'St. Elmo’s Fire,' he shows—with his role as a congressional assistant—that he was better off when typecast.”

Ouch.

The case can be made that this article helped these tropes all become a reality, but they all did wind up at least being arguably accurate.

But that’s what’s so interesting about ‘St. Elmo’s Fire' is that it captures this almost warped innocence of a group of people who all thought they were The Next Big Thing. Of course, Demi Moore had years of success ahead of her. And after his scandal, Rob Lowe reinvented himself by playing the villain in the comedies ‘Wayne’s World’ and ‘Tommy Boy.’ But, there’s something strangely pure about ‘St. Elmo’s Fire' today: it’s more a testament about celebrity and fame than it is anything the narrative of the movie is pretending to tell us. Here they all are with not a care in the world, all captured on film … not knowing that the party was just about over.

Mike Ryan has written for The Huffington Post, Wired, Vanity Fair and GQ. He is the senior editor of ScreenCrush. You can contact him directly on Twitter.[googleAd adunit="cutout-placeholder" placeholder="cutout-placeholder"]

More From ScreenCrush