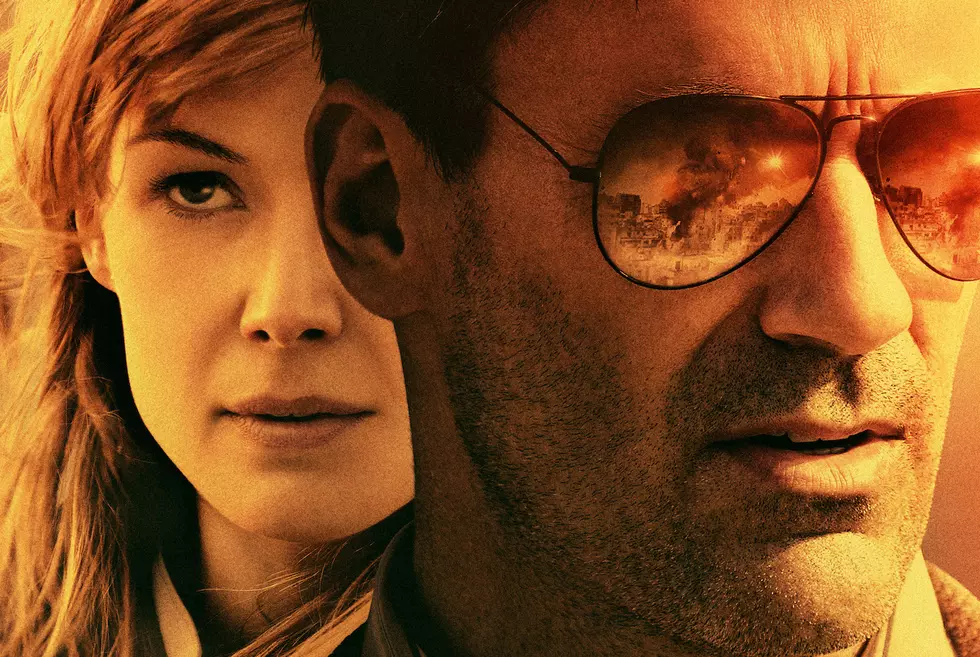

‘White Bird in a Blizzard’ Review

Indie auteur Gregg Araki has consistently used his films to explore drugs and dysfunction (with plenty of sex for added sizzle), so it’s natural that he would want to use his trademark point of view to address suburban malaise and a lingering mystery rooted in a bit of madness for his latest outing.

Araki’s ‘White Bird in a Blizzard’ centers on Kat Connors (Shailene Woodley), a seemingly regular teenage girl in 1988 whose world is turned upside down by the sudden disappearance of her mercurial and abusive mother, Eve (Eve Green). Set over the course of three years, ‘White Bird’ tracks the growing mystery surrounding what happened to Eve and how it changes the passionate Kat as she attempts to grow into a young woman. It may sound straightforward enough, but the film tries to twist wholly predictable plot points and trick normal narratives in a misguided attempt to bolster the damningly flat and poorly put-together feature.

‘White Bird in a Blizzard’ attempts to explore deep familial troubles and the nature of secret-keeping, but it’s so thinly and shallowly written that those attempts at profundity simply prove laughable. The film is crammed with exposition, as characters frequently spout hammy lines that only serve as an inelegant means of information delivery, and when that’s not quite enough, Woodley is saddled with laughably metaphor-laden voiceover work and frequent trips to a terrible therapist (Angela Bassett) to air out her issues and tell stories about her young life. It should come as little surprise that the film’s biggest revelation is delivered by way of voiceover and flashback. Nothing actually seems to happen within the actual timeline of the film, and the result is confusing, frustrating, and just plain lazy.

Yet for all that exposition and information dumping, the characters remain frightfully obtuse. Kat may be the center of all the action, but we don’t even know basic information about her, and it’s hard to fathom much of an interior life that doesn’t go beyond confusion about her mother and hormone-fueled lust. Adapted from Laura Kasischke’s book of the same, the hazy, dreamy quality of the film and its omnipresent voiceover most likely work far better as a written work, and Kat is probably a compelling (and more knowable) written narrator.

The film telegraphs its various twists early on, and its last gasp attempt at a shocking twist should be evident to anyone bothering to pay attention (though that doesn’t it make it any less contrived). Tonally, ‘White Bird’ is all over the map – first going for some awkward laughs, then some heady drama, before slipping into thriller and horror film territory. The film finally settles on the mystery of Eve’s whereabouts, but even that isn’t done with any kind of grace or urgency, and when the case is finally solved, it’s thanks to offhand comments and one hell of a coincidence.

Set in 1988 and 1991, the film lacks authenticity in nearly every way imaginable, from its flimsy-looking sets and poor lighting, to its attempts at approximating the very vivid years it tries to depict. The film imagines that kids in 1988 were still playing Atari, that a hip teen would still be rocking to a Cure song two years after it was released, and that it’s necessary to take a jumbo jet from Berkeley to San Bernardino (while the book was set in Ohio, a shot of a business card bears a California address).

Despite going the kitchen sink route on the time period at hand when it comes to fashion and music (the film is flooded with plenty of neon and even more Tears for Fears), Akari doesn’t bother to bog his characters down with eighties slang – instead, they talk like kids from today, with one character announcing she’s “Team Oliver” about a romantic choice for a friend, Kat calling her father Brock (Christopher Meloni) a douche, and Gabourey Sidibe’s character asking for “deets” on something. Somehow, Akari has managed to go whole Goldilocks on the production – too hot on certain trappings, too cold on others, with not a moderately crafted bowl to be found.

Woodley is unquestionably the best thing about the film, but even a talent like her falters by the film’s end, simply because the script and direction don’t require anything new from her, and even Woodley can’t make rinse-and-repeat crying and looking mad compelling after a certain mark. Elsewhere, Green is gloriously, unnervingly over the top, and if anyone is in the mood for rebooting ‘Mommie Dearest’ within the next few years, she should be the top pick for the starring role, as she’s essentially aping it here (without a wire hanger in sight). Christopher Meloni appears to be asleep for most of the film.

Araki’s supporting cast is just as talented and just as wasted as his leads. Thomas Jane pops up as a cop with no moral compass, and Shiloh Hernandez is tasked with playing Kat’s dim bulb high school boyfriend, a role at which he excels, routinely messing up common idioms with a straight face (though later scenes in the film ask him for more depth, which he cannot muster). Dale Dickey co-stars as Phil’s mother, a blind woman played to the point of parody, along with Sidibe and Mark Indelicato, who are boxed in as Kat’s misfit friends, the fat one and the gay one, respectively. (And, no, Araki’s film as little respect for any of them, a move made all the more jarring by Araki’s rich history exploring other maligned characters.)

‘White Bird in a Blizzard’ does benefit from a handful of dream sequences that, yes, imagine Kat searching for her mother in a blizzard, and it’s within those scenes that Araki’s spirit and technique truly shine through. Sadly, though, that sprit and technique are lacking throughout the rest of the film and searching for them (or much redeeming value in the film) is as fruitless as searching for just about anything amongst pelting snow.

'White Bird in a Blizzard' debuted at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival.

More From ScreenCrush