‘The Lost City of Z’ Review: An Epic Journey to Another Time and Place

Less than 100 years ago, there were still uncharted areas of this planet. In an age of cell phones, satellite images, and instantaneous access to the totality of human information, it can be difficult to envision such an era — at least until a film like The Lost City of Z brings it to vivid life.

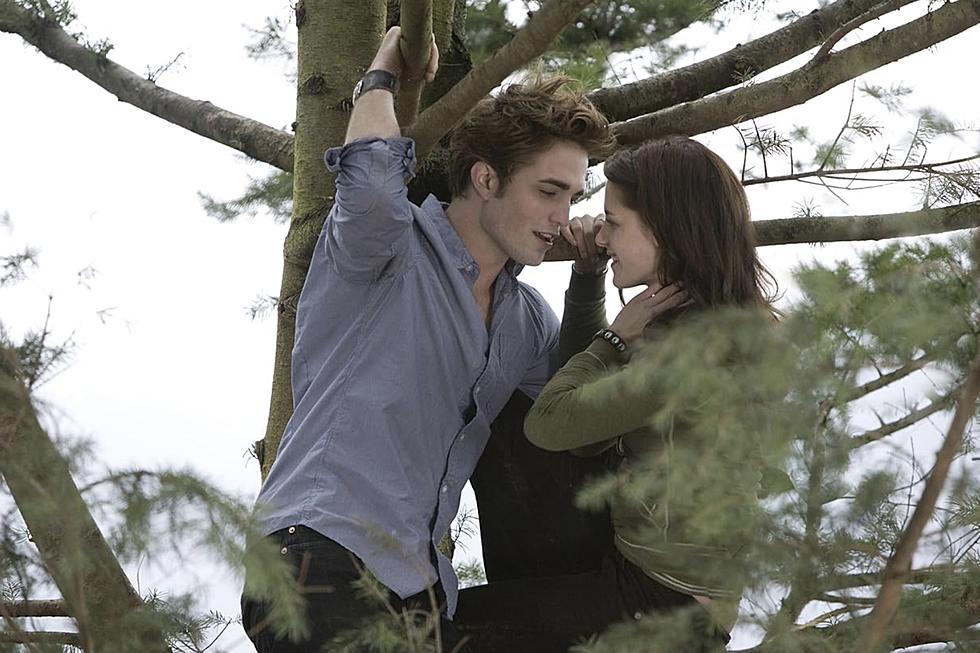

It is based on an article and subsequent non-fiction book by David Grann about real events in the life of famed British explorer Percy Fawcett, played here by Charlie Hunnam. With his career in the military floundering, Fawcett is eager for any opportunity for advancement. He gets one when the Royal Geographic Society offers to send him into unmapped areas of the Amazon in order to settle a border dispute between Bolivia and Brazil. On his first expedition to the region, Fawcett and his team (which includes a nearly unrecognizable Robert Pattinson beneath a bushy beard) find evidence they believe proves the existence of an undiscovered civilization deep in the rainforest. They call this lost city “Z.” (They’re British, so they pronounce it “Zed.”)

Fawcett’s journeys up the Amazon River evoke classic mad explorer movies like Fitzcarraldo and Apocalypse Now, but The Lost City of Z features a less fevered tone and a more deliberate structure. Fawcett doesn’t just wander into the jungle once, he ventures back to South America over and over again, leaving behind a family that he loves but cannot seem to stay with for any significant length of time. His wife Nina (Sienna Miller) adores him and supports his thirst for adventure, in part because she fashions herself an independent woman. But the years apart take their toll, and his children, particularly Fawcett’s oldest son Jack (Tom Holland), grows to resent the man who seems to like an imagined archaeological ruin more than his kids.

This is an unusual and fascinating perspective on some familiar tropes, and it transforms a remote story about an obsessive into a universal tale about the push and pull between every adult’s personal and professional lives. Every hour we spend pleasing our bosses is an hour we lose with our spouses and children, something Fawcett grappled with on a much larger scale because every trip to the Amazon, even the relatively successful ones, cost him years of his life. As time flies by, screenwriter and director James Gray draws superb performances out of Hunnam and Miller — the best either has given in many years — as a pair of well-matched partners who repeatedly allow the outside world to drag them apart.

That world is captured in stunning detail by cinematographer Darius Khondji, who manages to make both the Amazon and the English countryside look so ravishing that it’s easy to understand Fawcett’s dilemma, and to feel similarly torn between those two worlds. Anyone would be seduced by Khondji’s Amazon, but the rolling hills where the Fawcetts live are beautiful too, enough so that every time he returns home we wonder why he would ever leave. Khondji has been one of the world’s greatest directors of photography for decades, but he’s only garnered a single Oscar nomination in that time (for 1996’s Evita). If he doesn’t get his second nomination for The Lost City of Z, something is desperately wrong with the Academy Awards.

I won’t tell you if Fawcett succeeds in finding Z or not. (If you don’t want to be spoiled, I would avoid reading any Wikipedia pages about the film, book, or the real-life Fawcett.) But along the way to his final destination, there are superb interludes at home with his family, at the Royal Geographic Society (where superiors question Fawcett’s methods), and in the trenches of World War I, which Gray transforms into the site of a harrowing battle sequence. Some audiences may resist Lost City’s slow-and-steady pacing, but Gray’s film perfectly matches its subject’s methodical quest, which consumed decades of his life.

Through every trial and tribulation, Fawcett remains convinced of the existence of this ancient city from a forgotten time long ago. There’s a similar quality to The Lost City of Z; its unhurried pacing, complex themes, and magnificent visuals that must be seen on a big screen make it feel like an artifact from an era of big-budget filmmaking that has been rendered essentially extinct by the franchisification of Hollywood. Like Fawcett, Gray ventured into the unknown to unearth something that had been missing for many years. And he succeeded in finding it.

More From ScreenCrush