Reel Women: Scarlett Johansson’s Superpower Is the Ability to Make Sci-Fi More Interesting

In the last year, Scarlett Johansson has voiced a sentient operating system in Spike Jonze's 'Her' and played an alien striving to understand humanity in Jonathan Glazer's jarring 'Under the Skin.' This week, she tackles a different kind of sci-fi with 'Lucy,' a film that carries some of the same thematic DNA as her previous roles, though it isn't quite as intellectual -- nor is it as brainy as its titular character. But thanks to Johansson, the film prevails, giving us a wild and delightfully weird entry in the Scarlett Johansson Sci-Fi Collection.

Like 'Her' and 'Under the Skin,' 'Lucy' contemplates what it means to be human through the lens of science fiction, and director Luc Besson (who previously gave us strong female leads in 'Leon,' 'La Femme Nikita' and 'The Fifth Element') employs a sort of free association format, inserting footage of a gazelle captured by cheetahs early on as we watch Lucy become unwittingly embroiled with a criminal element. It's this encounter that sets Lucy down her destined path, when a recreational drug is sewn up inside of her and leaks out, pushing her brain beyond the limits of human possibility. Yes, it's sort of like 'Limitless' and a bit like a cooler, sleeker version of 'Transcendence' with a way more charismatic lead (and a supporting turn by Morgan Freeman included).

Besson draws an obvious parallel between Johansson's Lucy and Lucy, the name given to the remains of the first woman discovered by paleontologists. Our Lucy is intended to be the new first woman: the first woman to access the full capacity of her brain power, and the first woman to expand human consciousness by instructing us that we are limited only by the limitations we've imposed upon ourselves. Besson uses this story as a metaphor (however unwieldy) for the power of women; that Lucy chooses not to aggressively physically engage with those who antagonize her is telling, and makes the film's progression more interesting. Lucy is simply too smart, too powerful, and too strong to throw a punch. Life begins and ends with Lucy, both the first woman and the last woman in the film, and Besson's reverence for her is infectious.

Strangely enough, 'Lucy' serves as a sort of silly and shallow (this is not necessarily a bad thing) counterpoint to 'Under the Skin.' Where that film explored -- among many other things -- the idea of what it means to be human and the alien reality of existing as a woman, 'Lucy' contemplates how little it means to be human in a world so vast and infinite. Johansson's character in 'Under the Skin' arrived on a mission to kill men, but found herself distracted by our little microcosm of life. That film takes a studious and exploratory approach, as if Johansson is dissecting human beings in a lab to find out what makes them human. 'Lucy' is a much more verbose and frenetic enterprise, one that wears a lab coat and does a fair amount of posturing, but is far more abstract in its intentions than it initially lets on. It's not so much interested in studying what makes us who we are, as it is dismissing the smallness of our existence and (clumsily) pushing us into the realm of enlightenment.

But if 'Under the Skin' is about what it means to be human, than 'Lucy' is more about what it means to be inhuman -- superhuman, even. While it's been anticipated as Johansson's unofficial superhero film, there's little that's heroic about Lucy, which is what makes her -- like Johansson's 'Under the Skin' character -- more relatable. Lucy transcends beyond our own limited understanding of right and wrong and black and white, and it seems far too excellent for coincidence that by film's end, we watch as Lucy's body transforms into something sleek and black and shiny -- reminiscent of Johansson's alien character in 'Under the Skin.'

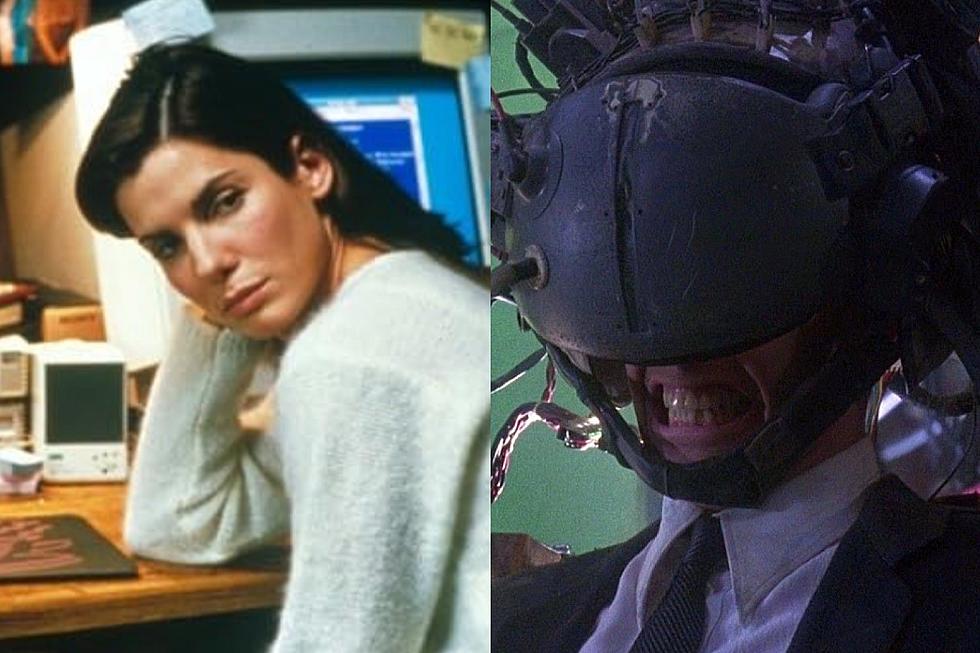

If you consider the two films side by side, they form a sort of ouroboros of abstract sci-fi: 'Lucy' dwarfs humanity as she realizes her full potential, and leaves the small human trappings of emotion and empathy and petty conflict behind, as if she is becoming alien to us. 'Under the Skin' puts humanity under a microscope (for better or worse), and we watch as Johansson's alien becomes human. In both films, the outcome is similar: Johansson is too good for us; we do not deserve her; our slight minds cannot comprehend the infinite, and it's that knowledge of and acceptance of the infinite that leads to this alien enlightenment.

These films are about the inherent flaw in humanity: our willful refusal to see or understand beyond ourselves, where the human is the microcosmic being inhabiting a larger microcosm, and we are so tragically limited. One film challenges our intellect, while the other exists in defiance of it, but both speak in an abstract visual language; perhaps because the only way we can begin to comprehend that which we do not understand (women, or life beyond our own; the latter also operating as a metaphor for the former) is by communicating in a language we all understand: a visual one.

More From ScreenCrush