‘True Detective’ Review: “The Locked Room”

On tonight's new episode of 'True Detective,' Hart and Cohle follow a lead that takes them into the heart of a religious ministry and has them contemplating the meaning (or lack thereof) of life. Meanwhile, Hart continues to face problems at home, while Cohle's tireless efforts off the clock may pay off in the lead they've been waiting for. There's no new episode of 'True Detective' next week, folks, but this one will leave a lasting impression while you wait.

Everything we do in this life is a struggle born out of a fear of imminent death -- all of our hopes and dreams, Cohle ruminates both in past and present day, are merely the one thing that we have in common: an imagining that we are individuals, that we matter, that we're important in the grand scheme of things and not merely some biological blip. All of these thoughts and desires are trapped, he says, in "the locked room" in our minds. But not even Rust Cohle, as much as he'd posture himself above such basic human feelings, is immune to this concept of self-importance. As we listen to him proselytize to both Hart in the past and to Detectives Gilbough and Papania in the present, what purpose do his florid monologues serve if not to hear himself speak -- and to know that he's right?

Cohle and Hart visit a traveling religious group, led by a charismatic preacher (Shea Wigham, a truly underutilized talent whose presence inspired me to shout "HELL YES"), where their debate over the value of life and religion and its purpose begins, which leads them into bickering with one another over their personal attitudes, as usual. The procedural elements take a backseat (Dora visited the church before it was burned down at its previous location; she was with a tall man with burn scars on his face) to the more contemplative aspects, but we're in the third episode now, and this stuff is just getting meatier, like digging into the rarer, juicier bits of the steak at the center.

And while Hart and Cohle bicker over whether Cohle is in denial (he is) and whether life has much value, what emerges is something more interesting: the way both men are so certain and righteous in their individual assessments of the world -- particularly Cohle, whose certainty about the darkness of the world bleeds over into an unnerving cockiness at times. What makes him that much different from a preacher like the one at the religious revival camp?

Hart and Cohle are both so certain that they are above the moral failings of the world as they perceive them. Hart talks about community and family, and even in modern day he clings to this idea that men need to make their families a priority, while in the past he's crashing into Lisa's apartment to attack her date and feeling threatened when he finds Cohle at his house, mowing the lawn and chatting with his wife. He is the classic alpha dog, peeing on his territory and growling rabidly at any male interlopers, refusing to let his females wander. Meanwhile, Cohle believes he's above the basic human conditions of loneliness and a need to feel important and make his life meaningful, but he spends his off-duty hours staring photos of dead women, trying to find their murderer's previous kill. Why dedicate your life to solving crime and protecting your little corner of the world from bad men if not to feel important in some way?

These are both men who are intensely critical, both of one another and the world around them, insistent that their perceived moral code is the right way to do things, whether it's Hart's ideas of family and community and faith, or Cohle's more rational musings about a society free of religion and zealotry, of men who cannot truly love and who must accept the darkness in themselves. What both of these men have in common is something we all have in common: that which we criticize most harshly in others is that which we despise the most in ourselves. All of their moralizing and proselytizing is merely and outward projection of the men they hope people perceive them to be; the men they want to be. We tell people what we believe in, what we think is right and wrong, in the hopes that they see us as the kind of people we want to be seen as; we are all desperately painting the picture of us with our words.

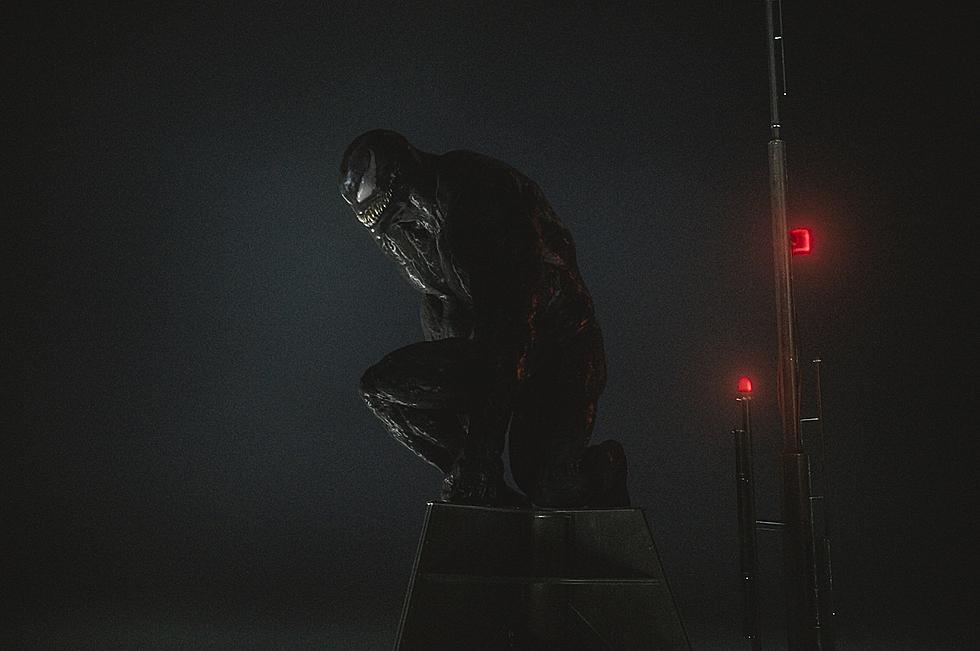

But I think Cohle's more on the level with who he is, at least in 1995: when Hart asks Cohle if he thinks he's a bad man, Cohle admits freely that he is, but it takes a bad man to keep the evil men from knocking down the door; it takes a bad guy to catch a bad guy. And lucky for them, Cohle's work paid off -- an old dead body, presumed to be a drowning, has ties to one Ms. Dora Lang. Our final shot presents us with our monster, the one that waited for Dora outside the locked room of her mind, deflating all those hopes and dreams and putting an end to the struggle she called life.

More From ScreenCrush