‘Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children’ Review: Tim Burton’s Middling Days of Future Past

Tim Burton’s movies have delivered diminishing returns in recent years as the director slides further and further into nauseatingly wacky computer-generated excess, with only the occasional glimmer of the gothic whimsy that made him a beloved household name. The good news is that Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children is a much better and more restrained film than Dark Shadows or Alice in Wonderland; the bad news is that it’s still a tedious YA adaptation with a half-baked metaphor about Burton’s career that might make you feel even more depressed about what the man has become.

Based on Ransom Riggs’ dark fantasy novel of the same name, Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children follows teenage Jake (Asa Butterfield) after the mysterious and gruesome death of his grandfather, Abraham (Terence Stamp). After years of hearing stories about Miss Peregrine and her school full of Peculiars (like X-Men but more Tim Burton-y), Jake is determined to discover — and prove — the truth; what he finds is a world tucked within our own, in which gifted children are kept hidden to protect them from a nefarious Peculiar (Samuel L. Jackson) and shadowy monstrosities known as Hollows.

The school’s eponymous headmistress (an unusually restrained Eva Green) is one of several “Ymbrynes” charged with hiding Peculiars in a safe location on a safe day and creating a time loop, allowing them to live in a single 24-hour period. This particular home happens to be on the Welsh island of Cairnholm in 1940, on the eve of a German bombing. There’s a Wizard of Oz-like quality to Jake’s journey, as Abraham’s tales of Peculiars and his many fantastical travels share a sorrowful connection to his Polish heritage and World War II — it’s one of the more interesting concepts in the film, but one which is only paid fleeting lip service.

Despite a two-hour runtime, much of the film feels rushed. Miss Peregrine houses an enchantingly odd collection of children, including Ella Purnell’s wispy Emma Bloom. But while each of them seems fascinating, most are only used as minor plot accessories and set dressing. Enoch (Finlay MacMillan) has the curious ability to bring things to life, but the mechanics are ill-defined — it has something to do with sticking an actual heart inside of an object or a dead person, but where do these organs come from? He’s so underdeveloped that he just sort of comes off as a sociopath who could easily become a serial killer if left to his own devices. Even Judi Dench — Dame Judi Dench! — is horribly wasted, reduced to a lame plot device and a series of skittish reaction shots.

The only real character development is fairly typical: The Peculiars make Jake feel special and, in return, he emboldens them to fight back against their tormentors. It’s very basic stuff, and despite Burton’s excessive tendencies, Miss Peregrine’s could use a little extra whimsy — a little extra anything, really, to bring this movie to life. That’s especially disappointing coming from Jane Goldman, the screenwriter who helped make X-Men: First Class and Kingsman: The Secret Service so entertaining.

And yet, hidden within Burton’s latest is a compelling metaphor for his career, a thematic State of the Union that only serves to make Miss Peregrine’s more frustrating. The central idea is that Peculiars are too strange for conventional society, so they must live in these preserved time loops in the past; if they were brought into the modern age, they wouldn’t survive. It’s easy to read Burton as a Peculiar; an anachronism whose odd proclivities have become increasingly difficult to sustain as technology and time evolves. Jake’s family home in the drab Florida suburbs could easily pass for the modern iteration of the uncannily colorful town in Edward Scissorhands, and Miss Peregrine’s estate features immaculate topiaries (including a T-Rex), just like the ones that Edward cultivated. Enoch’s grotesque animated dolls are evocative of Edward’s creator, and one even has scissors for hands. Each one is like a charming reverie, a sentimental Easter egg nodding to Burton’s brilliant past.

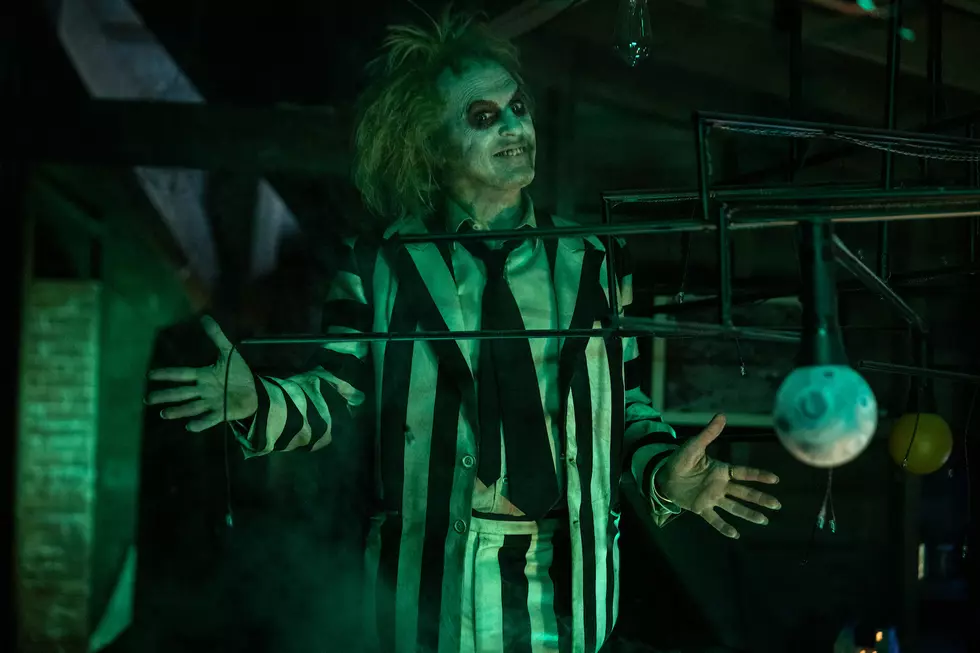

Ultimately, Burton gives into modernity with a climactic scene set at a boardwalk carnival, in which cartoonish skeletons march into battle against the Slenderman-like Hollows in a discordant CGI symphony set to a techno soundtrack. That musical choice has to be deliberate, as it highlights the jarring incongruity between the delightful camp of early Burton and the homogenized computerization of contemporary studio cinema. It’s a crass stylistic union, and one that proves that maybe Burton can only truly thrive in the past. Unfortunately, there is no magical time loop that will allow him to continue making movies in the years between 1982 and 1996. That loop has closed.

If this were a better, more entertaining film, Miss Peregrine’s could have been a thoughtful and bold metatextual thesis on Burton’s entire career. Instead, like its partially-formed villainous apparitions, it comes frustratingly close to achieving substance.

More From ScreenCrush