‘Waterworld’ at 25: Is the Most Notorious Flop in Hollywood History Worth Another Look?

The Universal Studios Beijing theme park is expected to open in the summer of 2021 with ten attractions based on movies. Nine of the ten — including Harry Potter, Despicable Me, and Jurassic World — are inspired by series with more than three movies, including at least one new sequel in the last four years. Just one of the ten attractions at Universal Beijing is from a franchise that began and ended with a single movie that’s more than five years old — and that one is based on one of the most expensive flops in history:

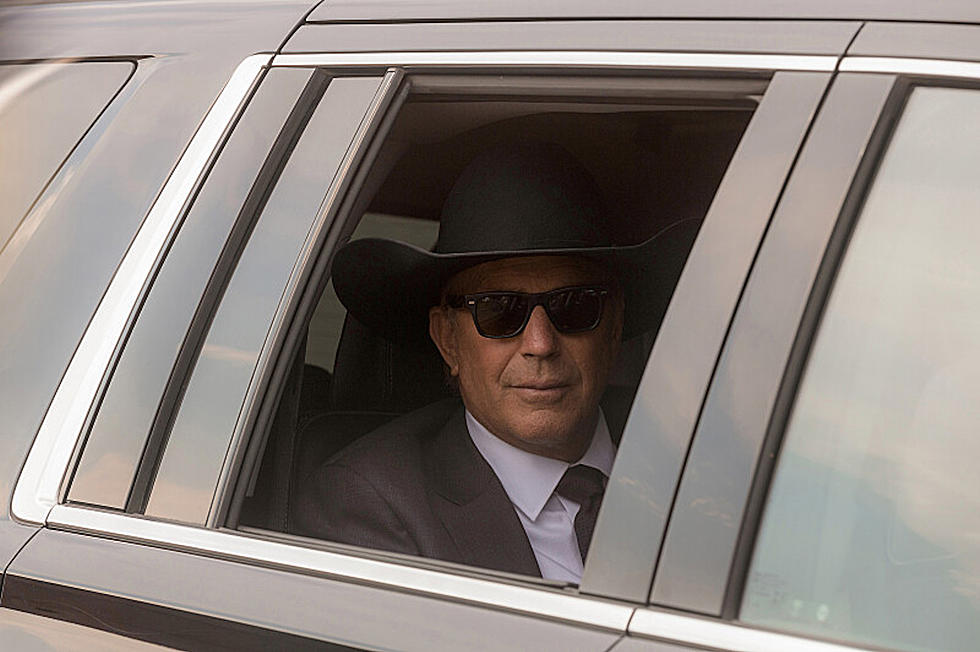

While Waterworld is perhaps the most notorious box-office bomb of the 1990s, Universal Studios’ Waterworld: A Live Sea War Spectacular remains improbably popular. Not only has the original Waterworld stunt show been in operation at Universal Studios Hollywood since shortly after the film premiered in the summer of 1995, the company keeps building more versions of it around the (water)world. They’ve replicated the Waterworld show at Universal Studios Japan, Universal Studios Singapore, and soon, at Universal Studios Beijing.

This kind of longevity is rare in theme-park attractions for movies people love, much less ones that are remembered only as trivia factoids and punchlines. Few would have predicted Universal Studios Hollywood’s Waterworld show would outlive the Back to the Future ride by 13 years and the E.T. ride by 17 years — particularly back in the summer of 1995 when reviews called the film “the most wasteful feat of one-upmanship in Hollywood history.” That wasn’t hyperbole; the film grossed only $88 million in U.S. theaters, a fraction of the $200 million Universal Pictures spent producing and marketing it.

At the time of its release, Waterworld was the most expensive movie ever made. Film magazines in the months leading up to its release were filled with reporting on its cost overruns and shooting delays. Universal originally budgeted some $100 million for the production, which was already a steep price at a time when the average Hollywood blockbuster cost $40 million. But one mishap after another befell the complex shoot; several water stunts went awry, threatening the lives of the movie’s stars, including Kevin Costner, who “nearly died during a sequence when he was lashed to the mast of his boat.” At one point a hurricane destroyed the film’s massive atoll set, which had to be completely rebuilt. After Waterworld sank at the box office, grossing just $21.6 million in its opening weekend in theaters, The New York Times called it “a symbol of Hollywood-style excess and ineptness.”

Someone who doesn’t know Waterworld’s infamous production history might be surprised by those descriptions in 2020. The movie Costner and director Kevin Reynolds made doesn’t look inept; it’s filled with detailed sets and vehicles and impressive chases and action set-pieces. Though it’s a large-scale production, it barely seems “excessive” by modern standards. Compared to a movie like Avengers: Endgame, with a cast of a couple dozen big-name actors and enormous battles spanning across time and space, Waterworld almost looks ... quaint.

Even if it’s set hundreds of years in the future, when global warming has supposedly melted the polar ice cap and flooded the entire planet, a lot of Waterworld now looks old-fashioned. For one thing, it’s almost inconceivable that a studio might spend $200 million 1995 dollars (the equivalent of $338 million today) on an original concept with no built-in audience. Waterworld was first conceived as an original idea by screenwriter Peter Rader — albeit an original idea that’s very clearly inspired by the post-apocalyptic adventures of the Mad Max series.

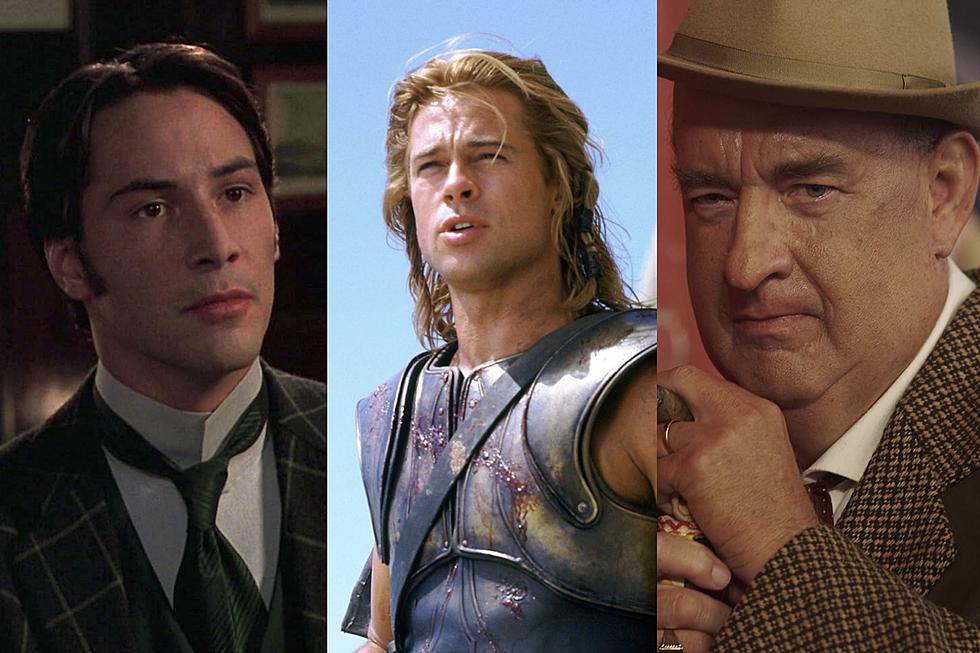

Of course, while the Mad Max films were beloved cult objects, none of the three entries in the series to that time had grossed $100 million in theaters, which suggests some financial flaws in Universal’s plan right from the start. The studio was banking on its star, Kevin Costner, who was riding a metaphorical wave of hits into the literal waves of Waterworld. In the early ’90s, Costner was one of the biggest movie stars on the planet. His 1989 baseball films, Bull Durham and Field of Dreams, became instant classics. He headlined a big-budget reboot of Robin Hood that became the second-biggest movie of 1991. He followed it with the second-biggest movie of 1992, The Bodyguard.

Early ’90s Costner had a Midas-like touch, even with seemingly uncommercial properties. With Costner at the center, Oliver Stone’s three-hour descent into Kennedy conspiracy theories became a blockbuster. Costner also helped revive the western genre with his epic Dances With Wolves; it was both a huge hit and an Oscar winner for Best Picture. Waterworld’s structure echoes Dances With Wolves, with a lone warrior out on an uncharted frontier, struggling to endure amidst the elements and dangerous enemies. If you had to bet on one star who could turn a bleak movie about the dirty, desperate survivors of an environmental catastrophe into a blockbuster, Costner made sense.

Of course, you didn’t have to bet on anything. No one held a harpoon to Universal’s head and forced them to spend a fifth of a billion dollars on a gill-man in striped pants who can swim really fast. They did it anyway.

Costner certainly works hard, but his character — a dour mutant named the Mariner, with gills and webbed feet — doesn’t exactly showcase his gifts. He’s introduced urine stream first, as he pisses into a cup and then pours the bodily fluids into a contraption to ready them for reconsumption. He swishes the pee water in his mouth and then sprinkles it on his boat’s one surviving plant. Can you believe this movie wasn’t a blockbuster?

Actually, the gadget that turns pee into water is one of the more interesting parts of Waterworld‘s ruined future, which is elaborately designed but barely explored. At least the secretion filtration system is an idea; after a few early scenes, the movie becomes a non-stop chase, with the Mariner as the reluctant guardian to a young girl named Enola (Tina Majorino) whose back tattoo supposedly contains a map to mythic “Dryland.” A group of “smokers” led by Dennis Hopper’s one-eyed Deacon want the girl, so they claim Dryland for themselves.

No one can figure out the correct interpretation of the girl’s map for the first 110 minutes of the film, and then as soon as all the bad guys have been dealt with, a character instantly figures out precisely what it means so they can rush to the happy ending. The rest of the movie is about Mariner, Enola, and her guardian Helen (Jeanne Tripplehorn) struggling to stay a breaststroke ahead of Deacon and his goons, which means very little time is spent investigating how a world built entirely on the watery ruins of our society might operate. Maybe that’s because it couldn’t, as any serious attempt to consider Waterworld’s premise would have exposed how silly it is. (The movie provides an explanation how Deacon keeps his boats and planes supplied with oil, but not how they continue to function so well hundreds of years after the collapse of civilization.)

Making a movie called Waterworld in a post-aqualypse and not fully surveying what life in it might be like is a bit like setting an action thriller inside a fireworks factory and then not setting off a single Roman candle. Why spend $200 million on ... this? Surely there’s a cheaper way to make a movie about dirty guys chasing each other on jet skis. Even if the three-hour “Ulysses Cut” of Waterworld was eventually released, the one that most people saw in theaters or on home video (or as a digital download, like I did last week) looked like a two-hour boat race in dystopia cosplay. While the Mariner discovers secrets about the origins of Waterworld in the ocean’s depths, the movie itself barely skims the surface.

Whenever a movie with a famously troubled production does poorly at the box office, there’s a rush to place blame on the bad press. Reporters were so critical, the argument goes, that people became convinced the movie was a disaster and stayed away. In this case, and in most cases, this is nothing but an excuse. Two years after Waterworld bombed, James Cameron’s Titanic got even more negative stories about its costly production. It went on to become one of the biggest hits in the history of motion pictures because it gave its audience romance and drama and appealing leads, along with some of the most remarkable special effects audiences had ever seen at that time.

Waterworld, in contrast, gave people a soggy Kevin Costner with webbed toes, a couple high dives, and some big explosions. In the end, maybe that’s why Waterworld is now remembered as a Universal Studios stunt show. Because when you get right down to it, that’s basically what it was all along.

Gallery — Incredible Movie-Based Theme Park Rides That Were Never Built:

More From ScreenCrush