‘Hell or High Water’ Review: The Criminally Entertaining Antidote to a Crappy Summer Movie Season

The road signs in Hell or High Water kept catching my eye. They’re like a Greek chorus commenting on the action in the foreground of the film. During the opening sequence, the robbery of a small Texas bank, the camera pans across the front of a Goodyear Tire Shop, which is basically a big middle finger to the two brothers carrying out the robbery. (Their mother has just died and they’ve turned to crime to make ends meet.) A few moments later they drive past a billboard that reads “Closing Down,” and there are also signs advertising “Debt Relief” and “Fast Cash,” all tempting (or taunting) these two men as they engineer a crime wave in West Texas.

The signs are not accidental. They reflect the care and attention to detail director David Mackenzie and writer Taylor Sheridan put into Hell or High Water, a suspenseful and purposeful thriller that uses the iconography of classic Westerns to tell a modern story of economic desperation. The brothers, Toby (Chris Pine) and Tanner (Ben Foster), break the law, but most of their crimes fall into a gray Robin Hood area of robbing from the rich to give to the poor (admittedly, in this scenario, they are the poor). They’re pursued by a Texas Ranger on the verge of retirement (a delightfully cantankerous Jeff Bridges). None of these characters are as good or as bad as they initially appear, and Mackenzie and Sheridan continue to ponder their sins all the way to their film’s final shot, even as they ratchet up the tension with chases and shootouts.

The film’s first shot, of a desolate Texas street, includes a pair of intertwined tires (Goodyears, no doubt), echoing the film’s linked protagonists. Upstanding Toby recruits Tanner, who’s just gotten out of jail, to help him execute a carefully orchestrated series of bank robberies. If they follow Toby’s plan, they could pull off the perfect crime. But Tanner is reckless and violent, and he keeps taking unnecessary risks. He leaves just enough clues for Bridges’ Marcus to figure out what the men are really doing and why.

Mackenzie and Sheridan keep cutting back and forth from the brothers to Marcus and his half-Mexican, half-Native American partner Alberto (Gil Birmingham). The two cops have amusing chemistry built on begrudging admiration and an endless series of playful insults. The parallel stories will inevitably intersect, but the filmmakers do such a good job of developing and humanizing both pairs of leads that we don’t want them to, since that would ask us to root for one side against the other. As the Rangers follow their leads towards toward the brothers, the anticipation for their meeting becomes almost unbearable.

Sheridan previously wrote the outstanding drug-war thriller Sicario; he specializes in stories that don’t sacrifice intelligence for excitement, set in moral minefields where even relatively honest people can be undone by a single wrong step. His new film utilizes Western imagery (one shot of Bridges deliberately evokes Henry Fonda’s famous porch lean from My Darling Clementine) but it still feels fresh and contemporary. Bad mortgages are a huge subplot running beneath the main storyline, and Texas’ relaxed attitude toward gun control provides some very dark humor during the bank robberies. This West ain’t old, but it’s still plenty wild.

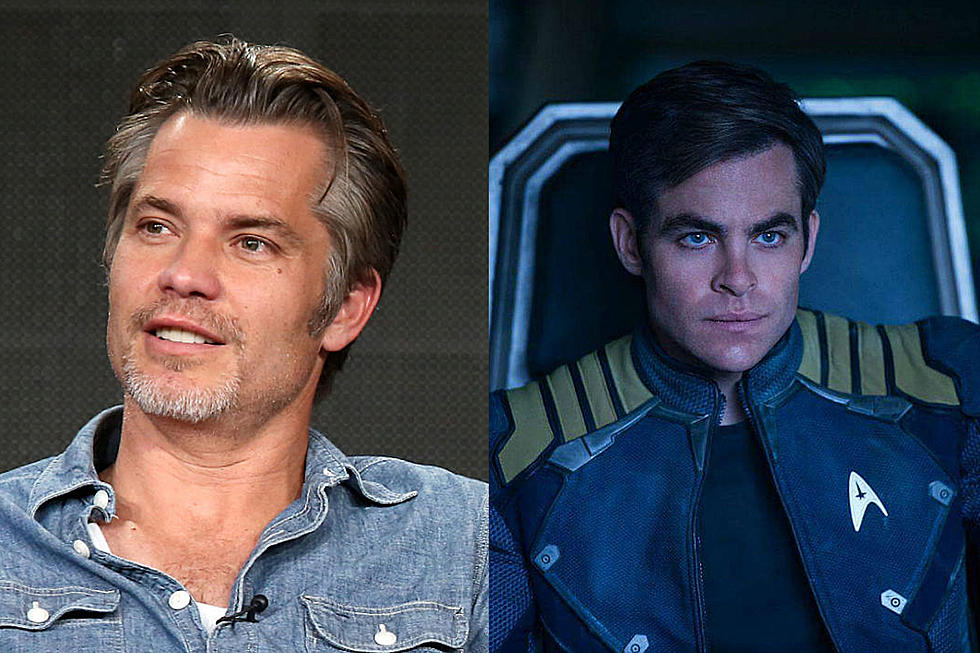

Foster is typically great as the loose cannon Tanner, and Bridges is hilarious playing one of my favorite stock Jeff Bridges characters: The Ornery Southern Lawman Who Sounds Like He’s Talking Through a Mouthguard. But the surprise standout is Chris Pine. Maybe because he possesses unfairly good lucks and outrageous charisma, Pine hasn’t received much recognition as an actor. He is outstanding in Hell or High Water. He gives Toby a sad, sagging posture; always hunched, eyes on the ground, as if the weight of all his responsibilities and mistakes are dragging him down physically as well as mentally. Casting Pine in the role makes good use of his onscreen persona as well. As the new Star Trek series’ Captain Kirk, he represents hope for a brighter, happier future. Having him play Toby suggests an end to that kind of optimism, and implies that small town America, with its empty storefronts and unemployed workers perched on the precipice of financial ruin, is our nation’s true final frontier.

Hell or High Water doesn’t have quite the same visual spark as Sicario, but Mackenzie has a good eye for sand-blasted images and he fills the bank robberies with nervous energy and impressive long takes. After each heist, the brothers zoom away in their stolen car, but Mackenzie’s camera always gives chase, catching up to Toby and Tanner just in time to overhear their post-crime arguments. No matter where these men go, someone is always following. No matter how much they steal, they will never be free.

More From ScreenCrush