‘Knight of Cups’ Review: Terrence Malick at His Most Experimental and Abstract

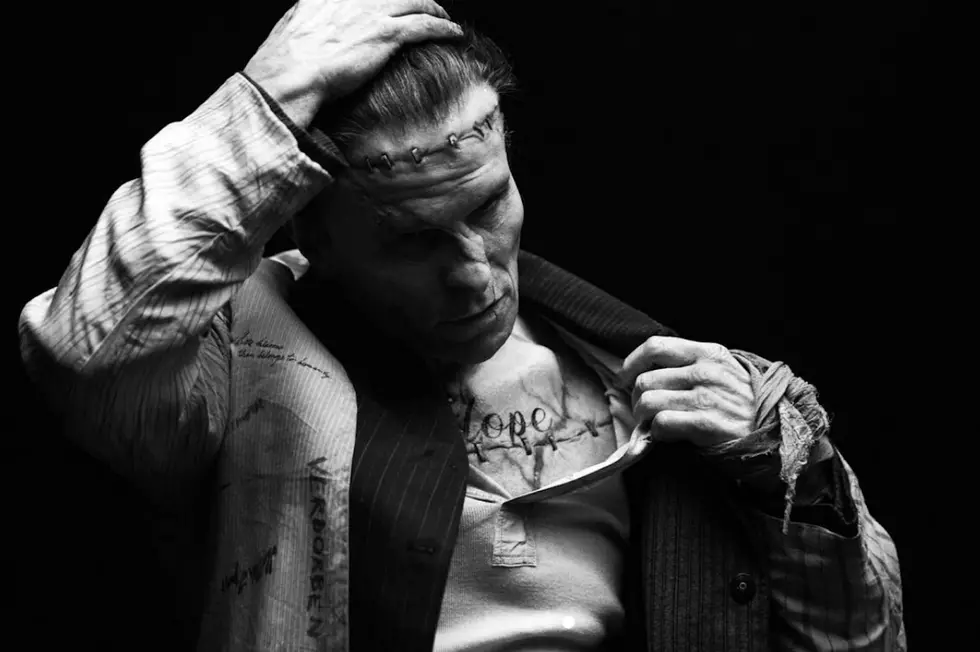

In a deck of tarot cards, the Knight of Cups can signal two sides in need of balance. The armored knight atop a white horse can be a sensitive man, though one controlled by his temperamental emotions. He can be imaginative, though a dreamer distracted by fantasy, a romantic, but selfish with desires for stimulation. When the card appears in the reverse in a reading, it can signify a life struggling in transition, and a descent toward recklessness or disappointment. So is the journey of Christian Bale’s Rick, a disenchanted Hollywood screenwriter in Terrence Malick‘s Knight of Cups; a knight trotting through a haze who seeks realization after he’s grown weary by the artifice that surrounds him.

Early into Knight of Cups, the seventh film from Malick, Rick visits a psychic who pulls the titular card in the upside-down position. From here we go on a scattered, non-linear journey of self-reflection in the usual Malick fashion of musing voiceovers and gliding visuals. The film, which is Malick’s first foray into a modern urban city, jumps from Ketamine-filled parties in Beverly Hills to memories of old lovers, from fueled arguments with his brother Barry (Wes Bentley) and father Joseph (Brian Dennehy) to phlegmatic shots of Rick wandering through a desert. Rick’s free-flowing journey, much like his “untethered soul” as Dennehy’s narration describes, is also broken into tarot-named chapters from The Moon to The Hangman to The Tower. But beyond that, don’t expect much cohesion, as this is undeniably a Malick film and one at his most experimental and abstract yet.

The film acts more like a collection of memories and a visualization of Rick’s consciousness moving between the past and present as he relives of old conversations. Besides the decadence of the Hollywood lifestyle, the tragedy that’s thrown Rick off course is the death of one of his brothers. This, along with references to Barry’s attempted suicide and another character’s comments about losing his hands, are strong allusions to the injuries and apparent suicide of Malick’s own brother Larry. While Malick most prominently focused on the loss of a brother and strained relationship with a father in The Tree of Life, Knight of Cups feels like the filmmaker’s most personal work yet.

Those exhausted by Malick’s loose-to-no narrative style and his whispery voiceovers will likely grow impatient with Knight of Cups. Like all of his work post-The Thin Red Line, it’s a film more content with presenting and exploring questions than finding conclusions. But whereas To The Wonder felt more like a misfire (a film that lost much of its emotional depth in vacant repetition), Knight of Cups shows something much more ambitious.

Here Malick plays with the very language of cinema, continually reinventing and challenging the ways in which it can be used. Instead of giving us any sense of developed characters, he uses his actors as symbols who form the pieces of an impressionist mosaic. Bale’s Rick is less a lead character and more of the vessel through which Malick explores his own anxieties, doubts and trauma. The hovering camera follows Bale through empty studio backlots and down the ultra-bright Las Vegas strip, both expressions of the falsity and inauthenticity of his surroundings. It swirls between his current and former romances, only to find a man chasing an idea of a woman and not the woman herself.

Each of the female characters, from Imogen Poot’s Della to Frieda Pinto’s Helen, from Natalie Portman’s Elizabeth to Cate Blanchett’s Nancy, represent something Rick is seeking, yet fails to maintain in himself. Nancy has selflessness, Helen has spiritual faith and Della has freedom, while Rick is only chasing it through romance. While his memories of the women are an attempt to reveal more about the desperation of his Knight in decline, they’re ultimately the weakest elements of the film as each of the women blends into one homogenous blur. Though Malick has six female characters here, seven including Cherry Jones’ brief appearance as Rick’s mother, he fails to make them more than stereotypical sketches of Rick’s fantasies. One could say their lack of development, like Rick’s, also function as metaphors for his journey, yet still, the women only exist for the sake of his struggle. Over such a long-spanning career, it’s still a shame Malick’s work features so few memorable female representations.

Knight of Cups is certainly Malick’s most challenging and messiest film yet. It doesn’t always work, and at many moments begins to get lost in its dizzying wanderings and clear moments of improvisation — it was so improvised, cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki was asked to not read the script. That, along with its fragmented style and failure to meet much of a resolution will likely turn even the most patient viewers frustrated. But it can’t be denied that it’s a film experience like no other. It marks a moment of sudden inspiration and experimental intrigue for Malick, who’s making movies more frequently now than ever before. It’s both an accomplishment in introspective, transcendent filmmaking, and a puzzle as imbalanced as the knight at its center. We may not quite be able to understand it, but Knight of Cups certainly feels like a work of a great talent who’s still figuring out what he’s trying to say.

More From ScreenCrush