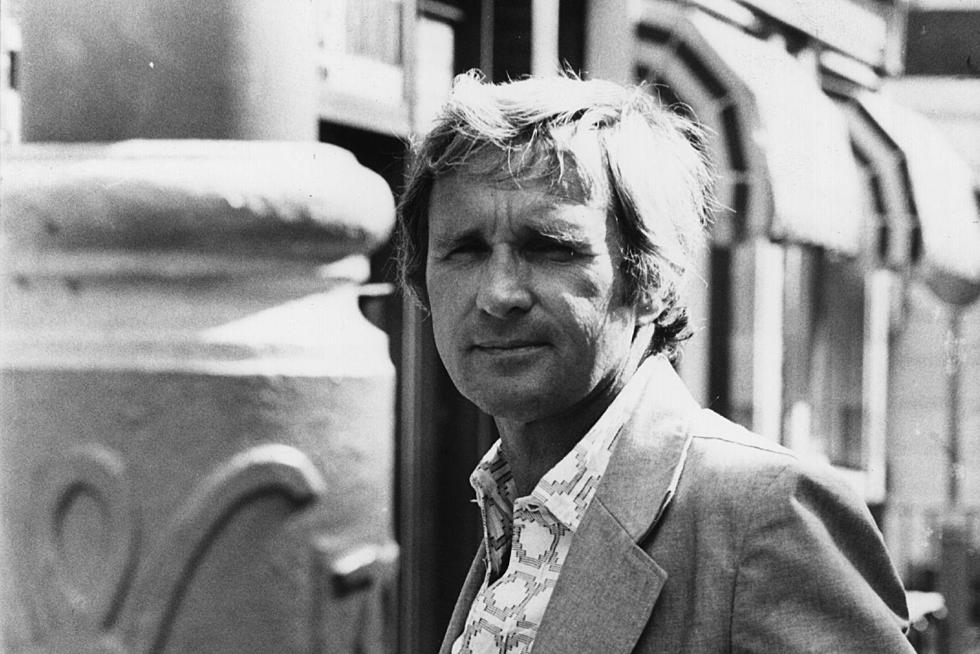

Groundbreaking Japanese Filmmaker Seijun Suzuki Dies at 93

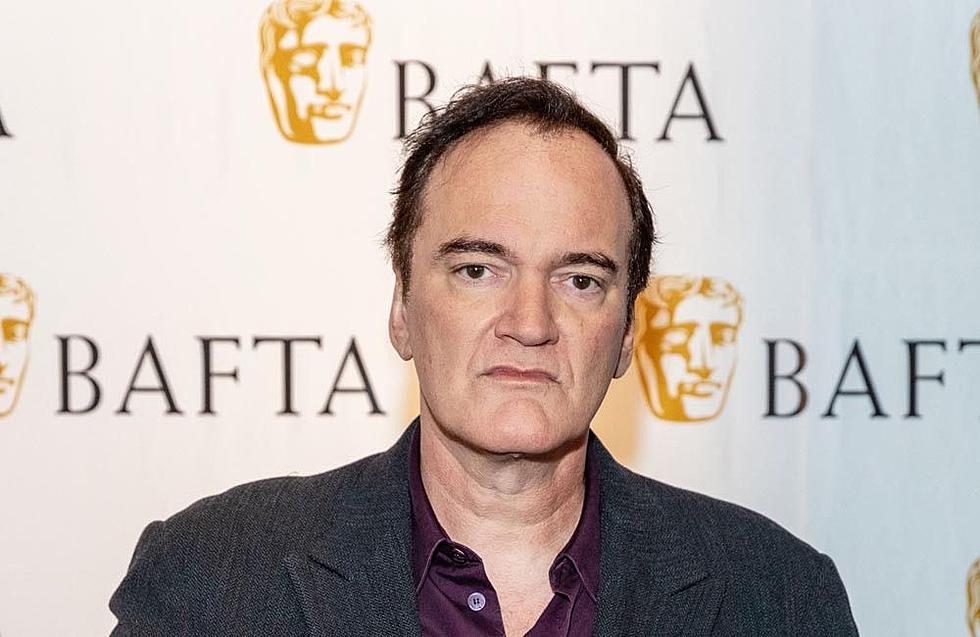

Of course, no individual could be fairly credited with having single-handedly invented the modern understanding of what it means to be cool, but Japanese filmmaker Seijun Suzuki is as good a place as any to start. With such films as Branded to Kill and Tokyo Drifter, he reimagined the gangster figure as an icon of bold sartorial style, unflappable stoicism, and casual Zen-like profundity. These films had a massive impact on pop culture; their influence would later trickle down to the cinema of Quentin Tarantino and Jim Jarmusch. But to ascribe Suzuki’s importance to his effect on others would be an insult; his films map an entire engrossing world unto themselves.

And now, they’ll stand as a monument to their visionary creator. The news broke last night that Suzuki died on February 13 at a Tokyo hospital following a protracted battle with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He was 93 years old.

Born Seitaro Suzuki on May 24, 1923 to a family in the textile industry, he enjoyed formal schooling from a young age and got in a bit of college education before heeding the call for soldiers during World War II. Combat didn‘t suit Suzuki, and after the war concluded, he ended up enrolling in the Kamakura Academy’s well-regarded film program after failing the entrance exam for the more-prestigious Tokyo University.

Following some minor assistant-directing work, it was on to Japan’s storied Nikkatsu Studios, where Suzuki repeatedly alienated his corporate overlords by delivering incomprehensible triumphs with plenty of artistic merit but little broad appeal. It was ultimately his crowning achievement, 1967’s Branded to Kill, that finally got him booted from the studio. Though he was cranking out three films per year on a shoestring budget, his adherence to avant-garde sensibilities would not stand with the money-minded studio bosses, and he got the heave-ho.

The lengthy legal battle with Nikkatsu occupied much of the next decade for Suzuki and nearly put him in the poorhouse. He didn’t mount another film until 1977’s A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness, and afterward, he never hit the same prolific pace he operated at during the ’60s. He spent most of his later years watching cinephiles rediscover his mistreated masterpieces, enjoying a high esteem in film circles while working on smaller projects.

The greatest honor a viewer could pay Suzuki today is to go find the films that went unappreciated in their own time and give them the respect they‘re due. Suzuki’s legacy lives on in the legion of disciples he leaves behind, but there’s really nothing better than the genuine article.

More From ScreenCrush