Uma Thurman’s ‘Kill Bill’ Accident Completely Changes ‘Death Proof’

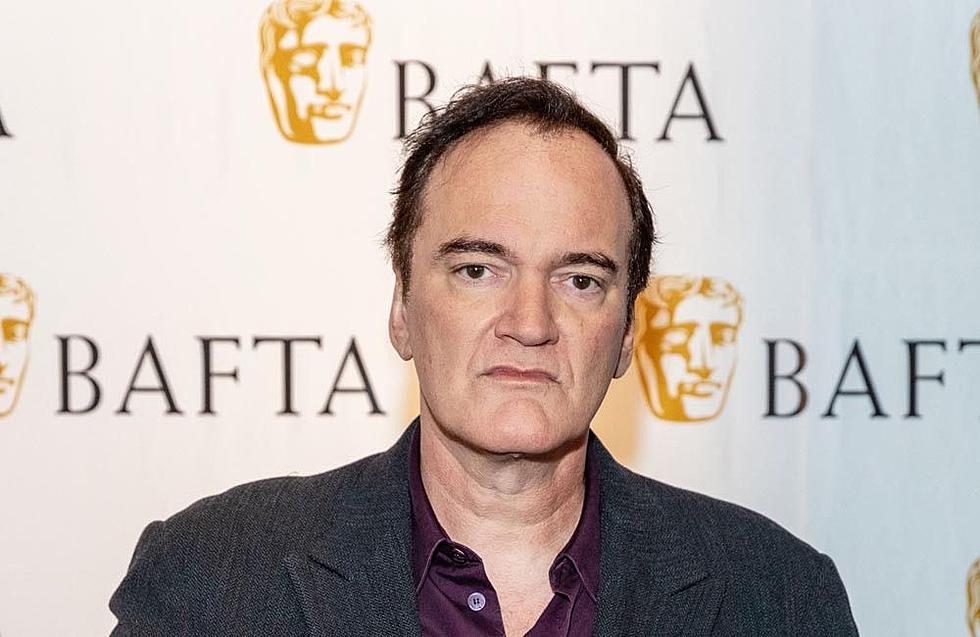

I always wondered why Quentin Tarantino and Uma Thurman never made another movie together after Kill Bill.

Thurman was the breakout star of Tarantino’s breakthrough, Pulp Fiction. Nine years later, they re-teamed on the two-part Kill Bill saga, which Thurman not only starred in but had a hand in writing; the credits acknowledge that her character, the Bride, was “created by Q & U.” Back then, Tarantino routinely described Thurman as his “muse” and “my actress.” He compared his working relationship with her to the one between director Josef von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich, who made seven films together. In a 2004 Rolling Stone profile of the pair, Kill Bill star David Carradine says Tarantino had told him “I want to be directing her for the rest of my life.” And yet here we are, over a decade and a half later, and the total number of their post-Bill collaborations is precisely zero.

That Rolling Stone profile offers some hints that things weren’t quite so peachy between Q and U, even if they were only visible in retrospect. Asked by Erik Hedegaard if she likes being around Tarantino, Thurman replied “Umm, I have in the past,” before correcting herself and insisting she does, even if he makes it difficult to get a word in during conversations. In his article, Hedegaard speculates that Tarantino and Thurman have an unrevealed romantic past, or at least that he is in some ways obsessed with her, and that this is the source of the mysterious friction between them.

The far more complicated truth only came to light earlier this month, with the publication of a New York Times editorial titled “This Is Why Uma Thurman Is Angry.” While much of the piece was about Thurman’s relationship with Harvey Weinstein, who produced all of Tarantino’s movies and, she alleges in the piece, sexually assaulted her, the chief source of her rage turns out to be a previously undisclosed accident on the set of Kill Bill: Vol. 2.

Thurman claims Tarantino “persuaded” her to perform a driving stunt she didn’t want to do. (He wanted to see her hair flapping in the breeze at 40 miles per hour.) She lost control of the car and crashed into a tree, leaving her with a “permanently damaged neck” and “screwed-up knees.” It took Thurman 15 years (and, ultimately, Tarantino’s help) to recover the raw footage of the crash, which Weinstein (and his previous company, Miramax) apparently refused to show to her unless she “signed a document ‘releasing them of any consequences of [her] future pain and suffering.’” As a result, Thurman and Tarantino were in “a terrible fight for years,” and their vaunted collaboration came to a screeching halt.

Instead, Tarantino shifted gears and moved on to an homage to exploitation films called Death Proof, a movie that looks drastically different in light of the revelation of that Kill Bill accident. Once you understand this backstory — that Tarantino went from making a movie where a stunt gone wrong seriously hurt (and permanently altered his relationship with) an actress to one about a stuntman who uses a car to hurt actresses — Death Proof transforms from provocative horror movie into one of the most fascinating (and sometimes troubling) works of Tarantino’s entire career; part self-critique and part exorcism.

Split roughly in half, Death Proof follows two groups of young women as they are hunted by a deranged stuntman named Mike McKay (Kurt Russell). As Mike likes to explain to his victims, his car is “100 percent death proof” — it’s been reinforced for movie stunts to protect its driver from any possible collision. After what happened on the set of Kill Bill, the fantasy of a car so secure it could protect its driver from literally any accident must have been a particularly intoxicating one for Tarantino.

Instead of recreating the Kill Bill incident, Tarantino twisted it into a malevolent slasher film, with Stuntman Mike using his death-proof car as a weapon aimed at any attractive woman who happens to pass through his rearview mirror. He stalks one trio of ladies and then, after successfully killing them in a crash, targets another quartet of beauties, all actresses and crew members from a local film production. This time, though, he picks the wrong prey, including a stuntwoman who’s even bolder and braver than he is, and they turn the tables and chase him down in their own classic muscle car.

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s obvious that Death Proof was at least partly inspired by the Kill Bill crash. It’s too much of a coincidence for it to be anything else. After pushing his leading lady to perform her own stunts, he made a movie where a stuntwoman (Zoe Bell, Thurman’s stand-in on Kill Bill) is the hero. (If nothing else, Kill Bill taught Tarantino an important lesson: If you want an actress to perform her own stunts, hire a stuntwoman for the part, not an actress.)

Death Proof is a movie about the perils of driving down dusty, winding roads like the one where Thurman’s Karmann Ghia skidded into a tree. It depicts old-fashioned stuntwork as potentially exhilarating (as when Bell rides on the roof of a speeding car for kicks) and fraught with peril that can sneak up on you without warning (as when Stuntman Mike emerges out of nowhere and drives Bell and her friends off the road).

It’s also a movie about men who pressure women into acts they’re not entirely comfortable committing. In the first half, radio DJ Jungle Julia (Sydney Tamiia Poitier) has told her listeners to find her and her friends in Austin, approach them, buy them a drink, and recite a Robert Frost poem. In return, Julia’s friend Butterfly (Vanessa Ferlito) will give the first lucky man to comply a lap dance. Butterfly obviously hates the idea, and she’s even less thrilled with it when Stuntman Mike turns out to be the dude to tell her the woods are lovely, dark, and deep. But he taunts her, and she eventually gives in.

These connections may seem like a stretch to you, and it wouldn’t surprise me in the least if Tarantino denied them. But Tarantino has previously said that all of his movies are “achingly personal.” “I may be talking about a bomb in a theatre,” he told one journalist who asked about autobiographical subtext in his films, “but that’s not what I’m really talking about.”

Tarantino has an onscreen role in Death Proof as well. He plays Walter, the jovial bartender of the establishment where Julia and Butterfly meet Mike. In the scene below, he also plies the women with free shots. There’s no choice in the matter, either; it’s a house rule, the waitress tells Butterfly. “If he sends over shots,” she explains “you gotta do them.” When she hesitates, Walter walks over and joins the group, exclaiming “I love that philosophy! Warren says it, we do it!” Sometimes he’s talking about bombs in a theatre, sometimes he’s talking about rounds of chartreuse. But that’s not what he’s really talking about.

Death Proof is not a simple film, and it’s not about one specific thing. It valorizes stunt people, but it villainizes them, too. It contains some truly disturbing violence against women — and also righteous (and grotesquely hilarious) retribution against men in the form of Stuntman Mike’s ultimate comeuppance.

If you questioned Thurman’s account of Tarantino persuading her to film that botched stunt, it’s worth watching this next video, a Blu-ray featurette on Death Proof’s car stunts. In the portion I’ve highlighted, Tarantino talks about working with Tracie Thom’s driving double,Tracy Keehn Dashnaw. “If Tracy said she couldn’t do it, we didn’t do it. Or we did it really slow. And then we realized she could do it and then we were like, little by little, add ten miles an hour to every take. If Tracy said she couldn’t do it, we’d say ‘Well, can you do it at 30?’ ... ‘Do you think you could maybe do it at 45?’ ... And eventually she’s doing it at 70.”

That doesn’t sound wildly different from the version of events on the Kill Bill set that Tarantino gave Deadline. He claimed he drove the stretch of road himself first to prove it was safe, then sold Thurman on the idea by saying “Oh, Uma, it’s just fine. You can totally do this. It’s just a straight line, that’s all it is. You get in the car at [point] number one, and drive to number two and you’re all good.” Unfortunately, Tarantino was wrong.

Most of the second half of Death Proof is a long car chase that stands amongst the greatest ever filmed. Some of the shots are absolutely staggering, like the one from the point of view of the driver’s seat in the women’s car as Stuntman Mike repeatedly slams his vehicle into their right side in one unbroken take. In another, the two cars do a jump, collide, spin out in traffic, and then get back up to speed. The result is absolutely exhilarating — and, now, somewhat discomforting.

On Death Proof, Tarantino worked with some of the greatest stunt performers in the history of the industry, including Buddy Joe Hooker and Terry Leonard. As far as we know, no one was seriously injured on the film — as far as we know. This whole affair is a reminder that stuntmen and women are incredibly important to movies and incredibly underappreciated. Even on a good day, their jobs are dangerous, and their achievements are almost always ignored. No one suffers quite so literally for their art. And yet there is no Oscar or Golden Globe for outstanding stuntwork. The stuntperson’s whole purpose is to remain invisible; if they’re seen, they break the illusion of the movie. That’s why Tarantino wanted Thurman behind the wheel of that Karmann Ghia, not Zoe Bell.

I still enjoyed watching Death Proof, even during its most perilous stunts. But it also made me think about the fact that someone (or multiple someones) were putting their lives on the line for my amusement in dozens, if not hundreds of the film’s shots, and I previously paid them almost no attention. I don’t think Tarantino should stop making movies, or even action movies with big stunts. But I do think directors have a responsibility to always put the well-being of their performers ahead of the well-being of their movie, and to consider the potential costs of their decisions.

Tarantino should understand that better than anyone. After all, if the Kill Bill accident did inspire Death Proof, then having it in our Blu-ray collections essentially cost the world a whole slew of Tarantino-Thurman movies like Kill Bill. In the final accounting, was it worth it?

Gallery - The Best Action Movie Posters Ever:

More From ScreenCrush