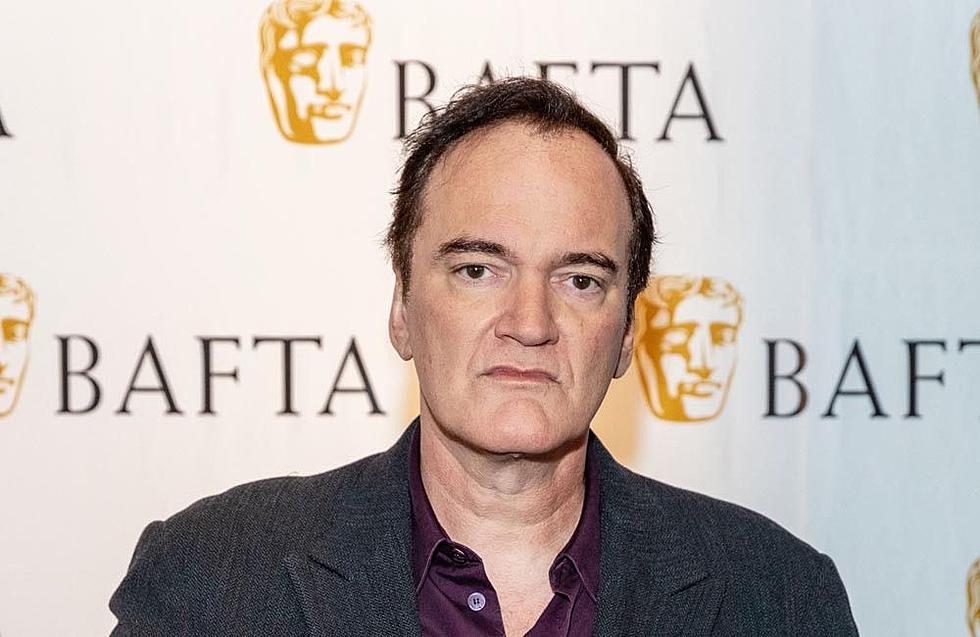

‘The Hateful Eight’ Review: Quentin Tarantino Makes the Old West New Again

Quentin Tarantino is the master of the comeback. Throughout his career, he’s rediscovered and revitalized the careers of one faded star after another; John Travolta in Pulp Fiction, Pam Grier in Jackie Brown, David Carradine in Kill Bill. Tarantino’s latest, The Hateful Eight, is his boldest reclamation project yet, an attempt to rejuvenate not just a single actor’s fortunes, but an entire medium of storytelling.

No one watches film anymore. Oh sure, they watch movies; on television, on laptops, on tablets, on cell phones, even in theaters. But the film — the actual, physical strip of chemically-produced images — that’s long gone. It’s back in The Hateful Eight, like a character in a Tarantino movie who’s killed in one chapter and returns from the dead via flashback in the next. Tarantino famously shot Hateful Eight in Ultra Panavision 70, and, in select locations, it’s being exhibited on 70mm film as well; in a three-hour roadshow that includes an overture and an intermission. If you have the opportunity to see it this way, do it. This is an ensemble picture where the true star is celluloid. Characters come and go, but the film’s presence is felt in every scene, like the ninth member of this depraved octet; in the magnificent Western landscapes, the precise framing of men and women in space, the incredible use of focus both deep and shallow, and in that tiny, nearly-imperceptible jiggle that happens when a strip of film gets projected.

In typical Tarantino fashion, the story concerns the lives of a ragged band of unsavory types thrown together by circumstance. A blizzard moving through the mountains of Wyoming in the years after the Civil War makes travel impossible for bounty hunter John Ruth (Kurt Russell), who’s trying to bring his prisoner, wanted murderer Daisy Domergue (Jennifer Jason Leigh), into the town of Red Rock to collect her reward. Along the road, their stagecoach meets another bounty hunter, former Union soldier Major Marquis Warren (Samuel L. Jackson) and later a former Confederate soldier Chris Mannix (Walton Goggins). Both claim their horses died; both need transportation to shelter before the blizzard arrives. Ruth, distrustful of both, reluctantly agrees, but remains paranoid that they might be working with his captive.

He’s right to be. Soon the coach arrives at Minnie’s Haberdashery, where the four characters and their driver, O.B. (James Parks), plan to wait out the storm. There they meet four more strangers: Señor Bob (Demián Bichir), who’s watching the place while Minnie’s away; Oswaldo Mobray (Tim Roth), the new hangman of Red Rock; Joe Cage (Michael Madsen), a quiet “cow-puncher” who’s in the area to visit his mother; and General Sanford Smithers (Bruce Dern), a Confederate officer who doesn’t take kindly to sharing his safe haven with a black man, much less one with Warren’s reputation for cruelty toward Southern rebels.

As the title suggests, some of these characters are not who they seem, and none of them can be trusted. There are no “good guys” in The Hateful Eight; all the characters are miserable scoundrels capable of shocking brutality. Joining the action in progress, and slowly teasing out the Eight’s backstories with lengthy exchanges of dialogue turns the movie into one giant poker game with life-or-death stakes, and Tarantino delights in prolonging the tension until the only way it can be released is through a relentless crescendo of violence that’s extreme even by his liberal standards. Tarantino’s movies have often climaxed with Mexican standoffs, like the old spaghetti Westerns of Sergio Leone (whose signature composer, Ennio Morricone, provides The Hateful Eight’s dread-drenched score). But The Hateful Eight is all Mexican standoff, a sustained, three-hour stalemate conducted at the ends of several large guns.

The men and women doing the conducting may be the finest ensemble Tarantino’s ever assembled. A script with this much dialogue (much of it deliberately obfuscating the characters’ true intentions) demands actors of the highest caliber, and Hateful Eight delivers a tremendous mix of Tarantino repertory players (including Roth, Madsen, Russell, and Jackson, giving maybe his finest performance since Pulp Fiction) and very appealing newcomers (including standout Jennifer Jason Leigh as the sadistic, racist, and surprisingly hilarious Daisy). There are much bigger movies this Christmas, filled with more elaborate visuals and stunts, but there’s no greater special effect this season than Samuel L. Jackson reciting a lengthy Quentin Tarantino monologue.

“Lengthy” may be the key word in that last sentence, and possibly this entire review. Some viewers will likely recoil at the prospect of a talky Western set mostly in a single, one-room location. Modern audiences have become weirdly averse to long movies, particularly ones that are light on action and heavy on talking. From the setting to the genre to the runtime to the graphic violence, everything about The Hateful Eight is unfashionable. But it’s all of a piece, designed by Tarantino to remind people why it’s just as satisfying to watch a three-hour movie as it is to bingewatch five episodes of cable television.

The Hateful Eight is doubly transportive, back to the Old West and to the days of the Old Hollywood, when movies were big and grand; true events, rather than mindless diversions. As he did in his Grindhouse double feature with Robert Rodriguez, Tarantino is playing with the boundaries of contemporary tastes and attention spans, and arguing on behalf of lost pop-cultural pleasures. “The name of the game,” as Warren says during a particularly tense exchange in the film, “is patience.”

Those willing to put in the time will find a movie that is both beautiful and hideous, funny and shocking, and even thoughtful on occasion; once it’s fully occupied, Minnie’s Haberdashery becomes something of a microcosm of America, one that, in Tarantino’s jaundiced view, is a melting pot where everyone gets burned. Those in power can’t be trusted, and neither can the people they’re protecting. You can take away people’s guns, but they’ll always find more. And when it gets really quiet, all that’s left is the howl of the blizzard wind and the sound of film through the projector.

Additional Thoughts:

-Tarantino’s credit in the opening titles says “The 8th Film by Quentin Tarantino,” and the whole movie is littered with references to his filmography. In fact, I spotted homages to every single Tarantino movie except one, though listing them all now would involve some spoilers, so let’s save that for another time and a separate piece.

-After Jackson, the MVP of the movie is Walton Goggins, channelling the great Burton Gilliam from Blazing Saddles, and somehow creating a character that is simultaneously despicable, terrifying, and utterly charming.

-The West really is the perfect place for a movie designed to take you away from modern life for three hours. There’s not a single phone anywhere in sight to remind you to check the device sitting in your pocket.

More From ScreenCrush