‘The Trial of the Chicago 7’ Review: The Whole World Is Watching on Netflix

No wonder Aaron Sorkin loves legal dramas. Sorkin characters are always talkers; Legal dramas are like gladiator movies where the heroes’ weapons are words and the courtroom is the arena. The conflicts in these worlds are so pure — prosecution versus defense, good versus evil — that there’s no need (or even a place!) for things like romance or subplots. it’s all about the struggle. And the words.

There are plenty of both Sorkin’s latest film, The Trial of the Chicago 7. Like almost every Sorkin screenplay of recent years, including The Social Network, Moneyball, Steve Jobs, and Molly’s Game, it’s based on a true story. The title sums it up: The heated 1969 trial of seven (initially eight) anti-Vietnam War protestors who were dubiously charged with inciting riots around the 1968 Democratic National Convention. In this case, history already looks like a Sorkin movie, with intense discourse about the importance of Constitutional freedoms, brave attorneys challenging the unfettered power of the United States government, and a judge so laughably biased against the defendants that he ordered one of them bound and gagged in the courtroom.

That’s Judge Julius Hoffman, played by Frank Langella as a slightly less evil version of his Skeletor from the live-action Masters of the Universe. The man he silences is Black Panther Party founder Bobby Seale (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), who quite clearly had nothing to do with the riots, having played no role in planning the protests in Chicago. That didn’t stop Judge Hoffman repeatedly antagonizing Seale, first by refusing to postpone the trial despite his attorney being ill, and then by not allowing him to represent himself in the attorney’s place. And that’s before he had Seale tied up and forcibly silenced.

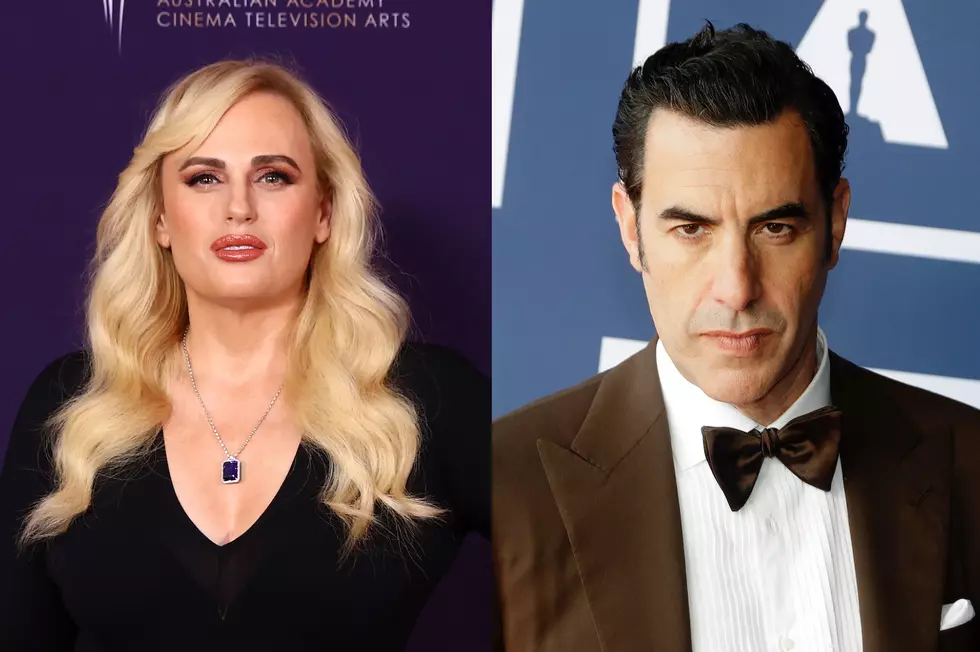

Langella and Abdul-Mateen are just two of the many familiar faces in the film. The Chicago 7 included many of the biggest stars of the anti-war movement of the late 1960s, and Sorkin has cast them accordingly. Sacha Baron Cohen and Jeremy Strong play Yippie leaders Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin; Oscar winner Eddie Redmayne is Tom Hayden of the Students for a Democratic Society, and Mark Rylance is their dogged attorney, William Kunstler. On the other side of courtroom, they’re opposed by Richard Shultz (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), who is portrayed as a sensible and fair U.S. Attorney who recognizes that the Chicago 7 are likely innocent but follows orders from his superiors, most notably Richard Nixon’s attorney general John Mitchell (John Doman), who demands they prosecute the Chicago 7 to send a message to liberals about the need to maintain law and order.

That’s one of the many parallels between The Trial of the Chicago 7’s 1969 and the 2020 in which viewers will watch the film on Netflix. Sorkin finds and emphasizes points of connection between then and now, including a Justice Department apparently working to settle scores on behalf of the President of the United States, intersecting movements of young, diverse protestors looking to push back against the conservative establishment, and highly questionable use of force on the part of police (who even remove their badges and identification before swinging their billy clubs at the kids on the streets in Chicago).

All of those similarities initially give The Trial of the Chicago 7 an added dash of suspense. The audience likely knows how the trial shook out in 1969, but just how these same issues will resolve in our own time remains unknown. They’re also hammered home so pointedly by Sorkin that they ultimately distract from the drama; occasionally, the film seems more interested in these characters as stand-ins for modern problems than as human beings trapped in a very dangerous situation. And Sorkin’s love of bombastic courtroom speeches serves him very poorly in The Trial of the Chicago 7’s climax, in which one of the defendants does something so out of character and so laughable it leads you to question whether it actually happened in the real court case. (And, in fact, it didn’t.) In those moments The Trial of the Chicago 7 looks less like the Oscar contender Netflix wants it to be than the sort of overly didactic made-for-TV movie high school history teachers play for seniors in the week between finals and graduation.

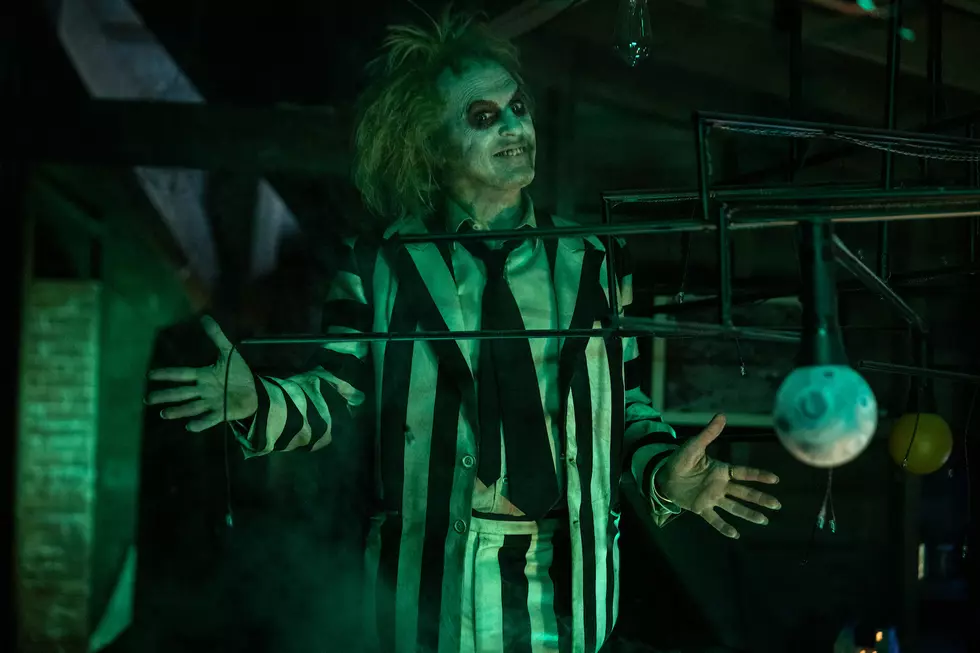

The Trial’s strongest material comes in the scenes where Sorkin revs up the editing and flashes between the courtroom and the events that sparked the trial, comparing the testimony to the events that “really” took place in a style reminiscent of the competing “truths” that ran through Sorkin’s script for The Social Network. There’s also a very memorable cameo from Michael Keaton, who shows up late in the film as a key defense witness. His grumbly, assertive performance is enough to fill your head with dreams of a larger collaboration between he and Sorkin.

Sorkin understands pacing and structure extremely well, although his skills in the visual area could still use some refinement. (In that regard, Sorkin makes a good match for Netflix and the home viewing experience.) As Sorkin screenplays go, The Trial of the Chicago 7 is a solid one, although not in the same league as a Social Network, where the dialogue was so instantly memorably you knew from the very first viewing that you’d be quoting it for eternity. The rallying cry of the Chicago protestors — “The whole world is watching!” — is repeated enough in Chicago 7 to suggest wishful thinking on Sorkin’s part. Given Netflix’s enormous base of subscribers, he wouldn’t be far off.

RATING: 7/10

Gallery — The Best Movie Taglines in History:

More From ScreenCrush